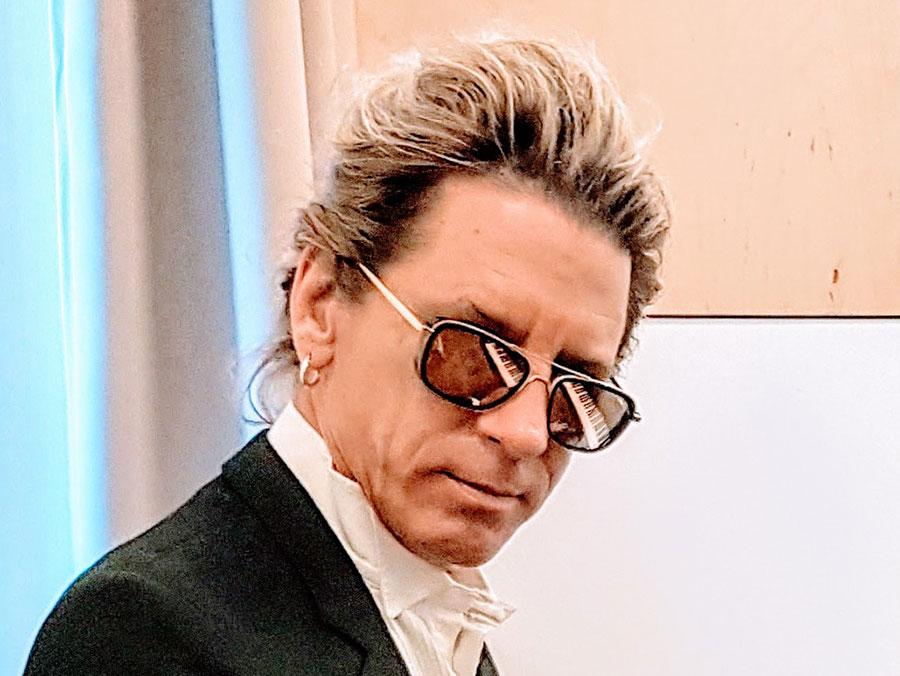

Celia Álvarez Muñoz ('82 M.F.A.) says she could paint pretty pictures all day. But it's not for her.

She wants to challenge the viewer.

"To build in levels of thinking is very seductive to me," she says. "I will lure you in with something accessible. And there's always something else to see beneath the surface. There's an image in there, but the image is connected to the thought process and the language allows you to move in different directions. So many words are signifiers that allure you to a meaning -- what it signifies, what it could be possibly be."

She's turned those ideas into objects and installations about a range of topics -- from women's issues to Latinx culture -- that have been displayed or commissioned from an elementary school in New York City to the Whitney Biennial, considered one of the world's most prestigious art exhibitions. Her decades of work have resulted in the 2020 Lifetime Achievement Award in the Visual Arts from the Houston Art League, been the subject of the book Celia Álvarez Muñoz and earned her the title of Texas State Artist 2D for the year 2022.

What does she hope that viewers get when they see her work?

"I hope they have a sense of validation," she says. "I don't make work that exposes suffering. I'm more about celebration of who we are -- the possibility and hope and of course ushering in the next generation."

Take one of her first notable pieces, The Enlightment, a series of artists' books and objects that played with the concept of language acquisition -- and the confusion that occurred while growing up in El Paso and trying to learn the differences between Spanish and English.

She made one of those installments when she studied at North Texas. She was 40 years old, had taught elementary school and raised her children when she entered graduate school.

While here, she created Number 4: Which Came First?, a book of photographs that featured pictures of chicken eggs and children's writing on a tablet, along with text in which the narrator tries to understand the difference between "lay," "laid" and "lie."

She says the piece was the first to be readily accepted by the public.

"The time was right, and it's always a matter of timing and positioning," she says. "The Hispanic/Latino community saw it as countering the forbiddance of the Spanish language in the school system, and I did not aim for that at all. It's all a matter of interpretation."

The Hispanic/Latino culture played a role in another one of her most notable works, Ella y El, in which the cabinet doors look like a shrine and showcase children's garments -- a little girl's dress and a boy's white suit.

"Conceptual art can be approached from many different avenues," she says. "Everybody was responding to multiculturism and people started building shrines.

And I thought, "How can I make one different from what I was seeing?"

For the piece, she employed a photographic technology called Cibachrome that lusciously reproduces the colors from transperencies, so it emphasizes the girl's dress and objects.

"The chemicals just highlighted those colors seductively," she says. "I think they were very readable. The cabinet houses a narrative and some of the objects in the photograph."

And as she gained more recognition, her artwork transformed from objects to large-scale installations for museums and other public spaces.

For the Capp Street Project in San Francisco, she worked with a group of LGBT youths for A Brand New Ball Game, a multimedia installation about coming out that looks like a game room, with a video, chessboard and vocabulary blocks. And for the San Antonio River Walk, she contributed El Rio Habla, The River Speaks, in which she embellished six landings that became water features with text and stone work at the Historic Civic Center River Link.

"Ideas are the drivers," she says. "What comes first? Does the word come first? Does the image first? Do I make sketches? Sometimes. It all starts with the written word, the typed word, the semantics, and with a basic No. 2 pencil. And research is a big part of the work. I have got to be continually exploring. And I have said this before, I'm restless. I like a challenge."

While at North Texas, Muñoz made a list of goals -- including winning a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, getting in the Whitney Biennial and seeing her work on permanent display -- that she achieved before the 10-year deadline she set for herself.

She encourages young artists to keep organized by compiling lists, calendars and journals.

"You do have to have goals," she says. "How else can you challenge yourself? For me I have to have that carrot dangling in front of me or the boot in the rear."