August 9, 2021

When Charlotte Decoster ('06 M.A., '12 Ph.D.) looked at the photos in her grandfather's possession, she saw more than just snapshots.

She saw a bigger story that needed telling.

Decoster's grandfather -- a medical doctor during World War II who was embedded with the Belgian army -- was there during the Liberation of Belgium from German occupation and helped victims in the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp after the liberation. Some buildings still stood in her grandfather's pictures, before the British burned the camp to the ground to prevent the spread of diseases like typhus and dysentery.

"There are so many lessons -- that's why we study the Holocaust," says Decoster, who first saw the photos as a 19-year-old college sophomore. "It is that paradigm of hatred, discrimination, prejudice and genocide in human history. The lessons learned are very personal for each person who studies the history of the Holocaust. But the big lesson is that your choices and actions have consequence for others and your community."

The world is a dangerous place to live, not because of the people who are evil,

but because of the people who don't do anything about it.

Albert Einstein

As director of education for the Dallas Holocaust and Human Rights Museum, it's Decoster's job to make those lessons accessible to the public -- a key part of the museum's mission to teach the history of the Holocaust and advance human rights to combat prejudice, hatred and indifference. The museum features testimonies from Holocaust survivors, along with quotes from notable figures like Albert Einstein, who fled Germany in 1932 shortly before Hitler attained power.

"The world is a dangerous place to live," reads one of Einstein's quotes etched into the museum's walls, "not because of the people who are evil, but because of the people who don't do anything about it."

The words remain relevant even now, particularly in light of recent events of racial hatred and the increase of antisemitism. That's why her work is so critical.

"I wanted to do something that makes a difference," she says. "The Holocaust is a field in history where we can learn lessons from the past and apply them to today."

Educating the masses

Holocaust artifacts are on display at the Dallas Holocaust and Human Rights Museum.

As a student at UNT, Decoster was a member of the history honor society Phi Alpha Theta, attended numerous conferences and meetings on historical topics, and worked as a teaching fellow. Her mentor, Richard M. Golden -- founder and director of Jewish and Israel Studies at UNT -- helped Decoster earn scholarships for her studies in Paris, Israel and Washington, and connected her to the Dallas Holocaust and Human Rights Museum.

"Mentors were the most valuable part of my experience at UNT," she says.

Post-graduation, Decoster joined the museum as education coordinator before moving up the ranks to her current position in 2019. In her role, she oversees curriculum development, professional development for teachers, ethics training, virtual field trips and school partnerships. She's helped program series like "Crucial Conversations," which in the past has delved into topics such as disrupting racism, and this year is focused on confronting antisemitism. The series is accompanied by an education toolkit that features resources from the museum.

"I love the friends I have made working at the museum," Decoster says. "I work with law enforcement, students and nurses. Law enforcement and nurses were complicit during the Holocaust, and the professional training offered here is to combat that by having hard conversations."

Local police departments can sign up to receive an unconscious bias presentation at the museum. The Arlington Police Department, she notes, sends their recruits to the training, and Baylor's Louise Herring School of Nursing enrolls in the museum's ethics course.

Corporal Patrick Knight of the Arlington Police Department says the department's recruitment classes have attended the Law Enforcement and Society presentation since 2017 gleaning important perspectives about history and the work they do.

"Dr. Decoster leads in a facilitated discussion about law enforcement's participation in the Holocaust," Knight says. "It is an introspective look at our own biases."

'History impacts us today'

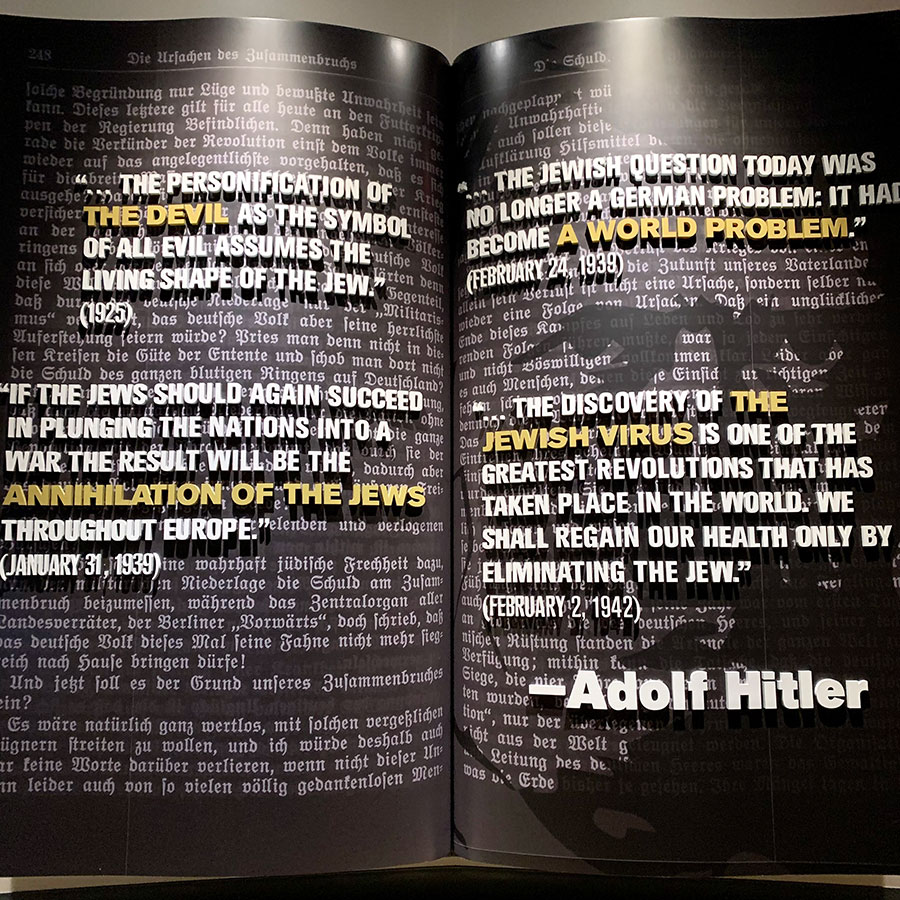

Adolf Hitler's words serve as a chilling reminder of the past as part of a display

at the Dallas Holocaust and Human Rights Museum.

The museum chronicles antisemitism from its earliest incarnations -- such as the Biblical persecution of Abraham and Moses -- to the Holocaust. The crushing oppression faced by European Jews is emphasized by a display of Hitler's quotes and audio recordings of his speeches. "Rational antisemitism," he shouts, "Its final objective must be the removal of the Jews altogether." The museum also includes examples of Nazi propaganda, and details of the Allied powers that stood strong against the Third Reich's insidious policies.

"This is not just a history museum but a human behavior institute," Decoster says. "All of it is impactful because it is about all of us as human beings."

Patrons can walk through a boxcar that transported Jews to concentration camps and visit the exhibit "Dimensions in Testimony," where they can sit with a hologram of a Holocaust survivor and ask them questions. Each survivor responded to a set of 1,000 questions, with the recordings taking place over a five-day period -- historical accounts made all the more vital as the last remaining survivors reach very old age.

"Soon, they will no longer be able to share their story in person," Decoster says. "Dimensions in Testimony provides a tool to keep their voice alive in a very interactive way. I can't wait to see this evolve in the future for not just Holocaust survivors but other genocide survivors as well."

One featured survivor in Dimensions in Testimony is Anita Lasker-Wallfisch, whose image appears through blue light and a humming projector. The audience learns Lasker-Wallfisch was born in Breslau, Germany, in 1925, the youngest of three girls, who describes her home as "happy." She was a cello player since childhood, moving to Berlin at age 12 to learn from a cello teacher. But at age 17, she was arrested at a train station after trying to escape to France and taken to Auschwitz. She and her sisters survived. She never saw her parents again.

There's also local Holocaust survivor Max Glauben, a native of Warsaw, Poland. He and his family were discovered by Nazis in 1943 and transported to Majdanek, where his mother and brother were sent to the gas chambers. He and his father were left to work in an airplane factory in Budzyn, where his father was killed. Glauben survived, and following liberation, immigrated to the U.S. and later settled in Dallas.

"That history is more than facts, research and books," Decoster says. "History impacts us today. It is filled with upstander role models who show us the path to a greater future. These upstanders' example impacts me every day. I learn from them non-stop. I strongly believe that education and learning from history creates a better future. I think our museum is that beacon to inspire people to become upstanders."

Hope for the future

Inspiring more upstanders, Decoster says, is the purpose of the Upstander Institute, a summer camp for teenage students hosted at the museum. The camp started in June, and engages students in the history of the Holocaust. The camp emphasizes hope over fear when it comes to modern hate, prejudice and discrimination.

"I meet amazing young people every day," she says. "They want to learn and are so open to the path to becoming upstanders -- that moment when you see that students understand the impact of the history displayed in the museum. It's the 'I get it' moment … I call it the light bulb effect. It happens at different points for students in the exhibit, but you can see it in their face. It's amazing and so rewarding. On the longest and most stressful days, it makes all the hard work so worth it."