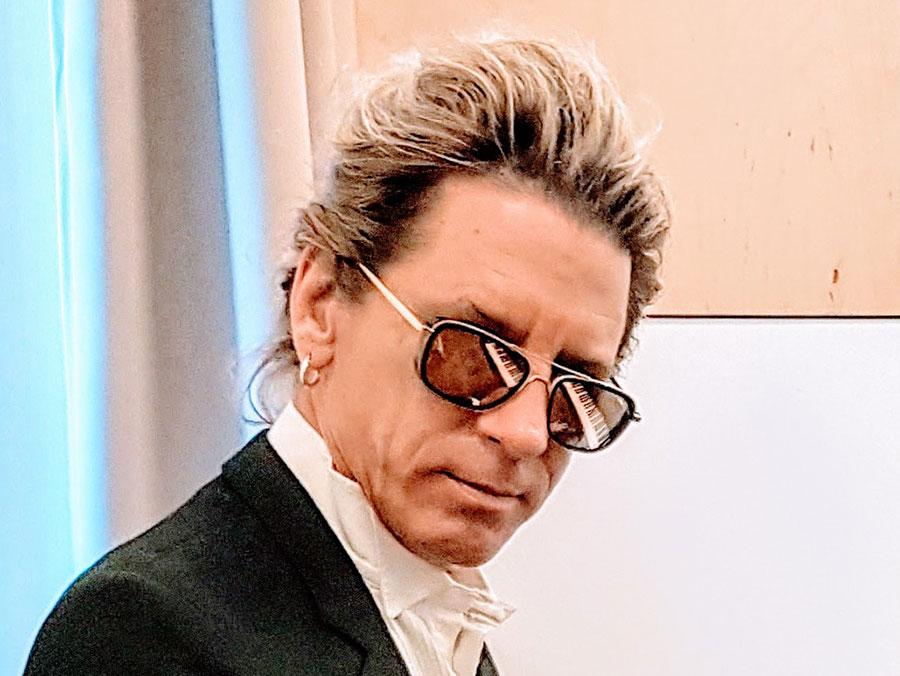

Seattle photographer Alex Garland ('06) was covering a Black Lives Matter protest when a distinctive sound reverberated through the air.

"I heard a shot," Garland says. "I know what a gunshot sounds like. I knew it was close."

The gun had been fired after an armed motorist attempted to smash through metal barricades and drive through the crowd. In order to stop him, a protestor ran up to the motorist, punched him and grabbed the steering wheel.

"I saw someone on the ground," Garland says. "I instinctively ran toward them."

The bullet hit the protestor's arm.

Garland, who always carries a trauma kit with him, began looking for an exit wound.

He couldn't find it, so he wrapped a tourniquet above the wound. Then, after a quick interview, he helped the man get into the ambulance.

That action earned Garland the National Press Photographers Association's 2020 Humanitarian of the Year. But Garland, who has drawn on his UNT emergency management degree while working at protests around the world, says he feels honored and humbled by the award.

"You know I kind of struggled with that a little bit," he says. "I only got this award because someone got shot and I acted in a humane way. There shouldn't be an award for this, but I'm very grateful to be recognized."

Garland hadn't intended to work in photojournalism. He moved to Seattle in 2010 for a change of scenery and with the plan to work as a wedding photographer.

When the Occupy movement started around 2011, he covered the protests and posted them on Facebook. Local editors noticed them, and in 2012, he began working as a freelance photojournalist -- traveling as far as Thailand to cover marches advocating for political reform.

He was intrigued by the marches for Black Lives Matter and indigenous and immigrant rights.

"It says a lot about people when they leave their home and take to the streets," he says. "So I think it's vital we show just how important these movements are to these people and let readers decide for themselves, 'Is this important to me?'"

But the protests can be dangerous and unpredictable. When he gives someone a bandage or other item from the trauma kit, he can get mixed reactions.

"There's surprise," he says. "There's a lot of gratitude. Sometimes people don't want help and that's OK. It's nice to be the one to offer that."

Sometimes, he's the one who needs help. His wife, Jessica Severance ('10), a theatre arts major who works as a freelance actor and performance artist, will wipe off the pepper spray from his clothes, then place them in a plastic bag to clean later, after he returns from a protest.

Garland has spent hundreds of dollars on personal protective equipment, including a gas mask, bulletproof vest and ballistic helmet. He has been arrested and spent the night in jail, resulting in post-traumatic stress disorder. He goes to therapy -- and takes hiking trips -- as a release.

But the mission is worth it.

"I really do value journalism," he says. "I think it is vital to our democracy."