Globe trekking librarian

Learn how ExxonMobil Corp.’s Lynnette Jordan helps manage information for the global company

Learn how ExxonMobil Corp.’s Lynnette Jordan helps manage information for the global company

Decreases in mortality rates, adverse drug effects, surgical complications — the clinical informatics team at Ascension Health searched its databases for statistics, with assistance from Tim Stettheimer (’00 Ph.D.), Ascension’s regional chief information officer.

The work would help a Los Angeles-based company determine if its evidence-based health care protocols and research, which assist health care professionals in applying evidence to the care of individual patients, were leading to improvements in care and recovery. Stettheimer worked closely with the team in planning ways to integrate this knowledge into clinical systems at hospitals operated by Ascension, the nation’s largest Catholic nonprofit health system, located in Birmingham, Ala.

“In medical informatics, the work you do makes a huge difference in others’ lives because you’re supporting advances in medicine and health care,” says Stettheimer, who became a student in UNT’s interdisciplinary doctoral program in information science to combine his interests in health care and technology.

“There’s an enormous amount of information being generated from medical research. It’s impossible for physicians to fully keep up,” Stettheimer says. “That’s why we have a need for clinical informaticists and medical librarians to determine database search terms. In addition, there’s a vast amount of medical information out there on the Internet — some of it inaccurate. The health care field needs people who are trusted sources of information.”

Stettheimer is one of many graduates of UNT’s College of Information who are using their master’s or doctoral degrees in library or information science in settings beyond public, school, college or university libraries.

“The new revolution is the information revolution,” says Herman Totten, dean of the college. “Companies know that information is their most prized commodity, and almost every entity needs information specialists.”

A recent report on “Best Careers” in U.S. News & World Report called graduates of library and information science academic programs “high-tech information sleuths, helping patrons plumb the oceans of information available in books and digital records, and often starting with a clever Google search but frequently going well beyond.”

No longer fitting the stereotype of “Marian the Librarian” — the bookish and standoffish spinster who constantly shushes library patrons in The Music Man — today’s librarians are technology-savvy, working more with computers and databases than card catalogs and paper records.

At UNT, the technology revolution resulted in the School of Library and Information Sciences — which was established out of a department in the College of Arts and Sciences — becoming the College of Information in fall 2008. In February 2009, the college’s commitment to teaching students about the links among people, information and technology applications led to its designation as an iSchool, an emerging academic program in information management, by the iCaucus.

The iCaucus was originally started in 1988 by deans of three schools and colleges of information and grew in the 1990s to include deans at more schools and colleges. In 2003, they adopted the term “iSchool,” or information school, to describe their institutions and “iCaucus” to describe themselves.

UNT is one of only two Texas colleges or universities represented among the 27 iSchools in Asia, Canada, Europe and the U.S. The iSchools promote interdisciplinary approaches to understanding information management and are committed to concepts such as universal access and user-centered organization of information.

As early as the 1970s, the then School of Library and Information Sciences curriculum included technology-based instruction, responding to needs from industries for librarians to manage computer databases and other information storehouses.

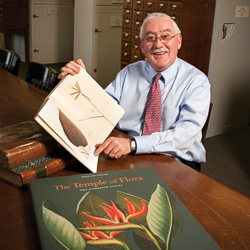

Gary Jennings (’74 M.L.S.) recalls using a card catalog to look up information when he was an undergraduate at Western Washington University in Bellingham, Wash., and working in the campus library.

“I’d been interested in computers and information technology, but it never entered my mind to use computers in libraries until I went to North Texas,” says Jennings, now the librarian for the Botanical Research Institute of Texas in Fort Worth. “I took classes in library automation and learned new methods of looking at information.”

Today’s students earning master’s degrees in library science and information science choose one of 10 program emphases, including digital image management, distributed learning librarianship, health informatics and information systems. Cybersecurity was added last fall.

Regardless of their program emphasis, all students take three core courses focusing on information acquisition, organization, and access and retrieval. This knowledge “makes it possible for our students to work in any area of the field,” Totten says.

Jana Hill (’00, ’03 M.S.), associate registrar of collection information for Fort Worth’s Amon Carter Museum, says the digital image management emphasis in the master’s program combined her interests in art and technology while appealing to her love for organization. In her job, she catalogs and digitizes the museum’s 250,000 permanent holdings as well as loans and special collections.

Hill says her clients include the museum’s curators, other museums’ registrars, educators and sometimes artists of the works.

“You’d be surprised to learn how many librarians do end up in museums, which need information professionals on their staffs,” she says.

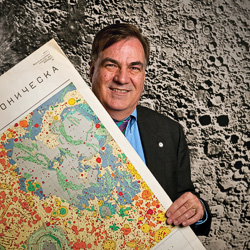

David Bigwood (’93 M.S.) digitizes and catalogs tens of thousands of photographs as assistant manager of library services at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, a research institute funded by NASA.

“We make all imagery brought back by NASA missions available to the public and catalog and tag it for metadata. Anyone can come to the institute and look up information in one of our catalogs, but the size of the datasets and collections can be daunting. We often have 200 or 300 CDs from one mission,” he says.

Like Hill, Bigwood majored in history for his bachelor’s degree. Totten says many students in both the college’s master’s and doctoral programs have fine arts, humanities, mathematics, science and social science backgrounds.

He notes that while about 50 percent of College of Information students still intend to work in traditional library environments, the other 50 percent intend to work for government and corporate libraries and information agencies.

Other College of Information alumni switch from traditional to non-traditional environments. Jennings worked in general reference, the Dallas/Texas history archives and branch libraries for the Dallas Library system for 21 years before being hired by BRIT in 2001.

“We have not only inhouse researchers, but many visiting researchers who need to know what others have learned about a specific plant when they study it,” says Jennings. He notes that special libraries like BRIT’s have widened their audiences over the years, adding that he also assists gardeners, naturalists, teachers and high school students doing special projects.

“In her reference courses at North Texas, Margaret Nichols (now a Professor Emeritus) taught the importance of being leaders in retrieval of information,” Jennings says.

That’s what Totten wants all graduates of the master’s and doctoral programs in library and information science to become. He predicts the College of Information will become one of the leaders of the iCaucus by 2014.

“We’ve been highly responsive to the needs of industry and, despite the economy, our enrollment grew 7 percent this past fall,” he says. “We are truly a pacesetter in a field that is almost recession proof.”