Ima Jean Sanders was just 13 when she left her home in Warner Robins, Ga., in 1974 and never made it back. Skeletal remains found two years later in a wooded area in nearby Peach County, while thought to be hers, could not be identified.

But nearly 40 years later in 2011, FBI program manager John E.B. "JEB" Stewart ('88 M.S., '96 Ph.D.), employing advances in forensic science and the national missing persons DNA database, matched the DNA profile from the remains with those of Ima Jean's mother and sister. A serial killer who claimed to have murdered more than 30 people was linked to her stolen life.

But nearly 40 years later in 2011, FBI program manager John E.B. "JEB" Stewart ('88 M.S., '96 Ph.D.), employing advances in forensic science and the national missing persons DNA database, matched the DNA profile from the remains with those of Ima Jean's mother and sister. A serial killer who claimed to have murdered more than 30 people was linked to her stolen life.

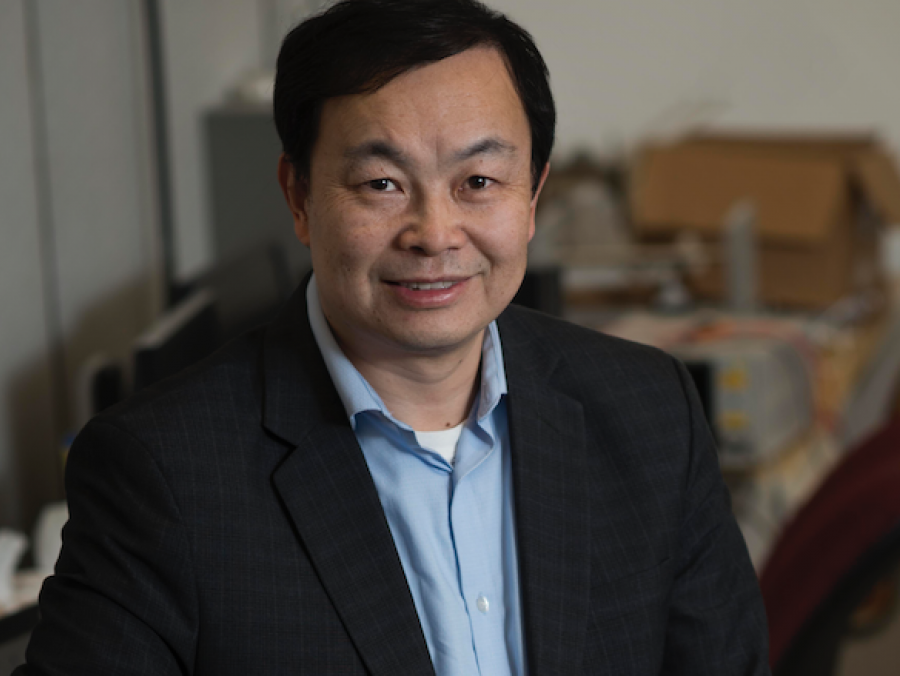

Stewart, who has been with the FBI in Quantico, Va., for 18 years, initiated the database program in 2000 and has helped law enforcement agencies nationwide by providing investigative leads for missing person cases. He also is an expert in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which is maternally inherited.

"Using mtDNA and nuclear DNA, we were able to provide the information needed for a medical examiner to identify Ima Jean's remains and close that case," Stewart says.

From Texas to the Middle East, alumni like Stewart, armed with their UNT educations, are leaders in the forensics field, matching DNA samples to criminals and missing persons, investigating crime scenes, training lab technicians and teaching the next generation of forensic scientists.

Prepared mind

In addition to the science education UNT provides at all levels, the university offers a forensic science undergraduate program -- one of only two such accredited programs in Texas. Launched in 2005, the program brings together a number of scientific fields with the goal of gathering information and piecing together stories to solve crimes and answer questions.

More on forensic science at UNT

Students in the program have access to cutting-edge laboratory equipment, including mass spectroscopy imaging and gas chromatography, and they learn from distinguished faculty, including world-renowned forensic anthropologist Harrell Gill-King, professor and director of the Institute of Forensic Anthropology at UNT. Gill-King also is co-director of the Center for Human Identification at the UNT Health Science Center in Fort Worth, which is home to the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System, the largest data source for unidentified remains cases in the country. Gill-King has helped identify victims of the Oklahoma City bombings, the World Trade Center tragedy and the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster.

"There's a great saying I tell students: 'Chance favors only the prepared mind,'" Gill-King says. "The success of so many alumni in forensics is a testament to the strength of our students and the teaching and mentoring they receive at UNT. We prepare them to jump in when great learning or job opportunities come around."

Solving cold cases

Stewart and fellow UNT alum Douglas Hares ('91, '98 Ph.D.) are among the more than 500 scientific experts from the FBI Laboratory who are deployed worldwide to provide operational and forensic assistance in criminal investigations.

With an interest in studying DNA and genetics, Stewart came to UNT as a master's student in professor Earl Zimmerman's biology lab. Later, he worked closely with Gill-King and the late biology professor Gerard O'Donovan while earning his doctoral degree. Stewart says he gained the background knowledge needed for a career in forensic DNA analysis by studying molecular biology and microbiology with O'Donovan. He also went into the field with Gill-King to learn how forensic anthropologists search for and recover human remains.

"The experiences I had at UNT really prepared me for my career," Stewart says. "My professors knew I was interested in DNA research and guided me there while helping me tackle related subjects by conducting laboratory research and field work and teaching biology and physical anthropology courses."

Hares manages the National DNA Index System (NDIS), which contains 13 million DNA profiles of known criminal off enders and 600,000 forensic DNA profiles recovered from crime scenes. Operated by the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS) software, NDIS provides leads for investigators across the nation in cases where biological evidence has been recovered.

"We can take forensic unknown DNA samples from crime scenes and compare them through our system to help solve cold cases," says Hares, adding that they're able to process DNA from a drop of blood or other bodily fluids collected from crime scenes. "It's very rewarding to help solve these cases."

Hares found his interest in forensics during a biochemistry lecture given by Robert Benjamin, associate professor of biology. Benjamin was discussing Trimboli v. the State of Texas, a 1985 triple homicide case in Arlington that was tried three times due to a hung jury and misconduct. By the third trial in 1989, science had advanced enough for criminals to be identified based on DNA at the crime scene and courts began allowing DNA evidence to be introduced in criminal proceedings.

"Before the third trial, DNA samples found at the scene were brought in as evidence," says Benjamin, who served as an expert to help coordinate the information and discuss with attorneys the heavily-debated DNA testing results. "It was the first real knock-down drag-out DNA case in the nation."

Listening to the lecture, Hares knew he was hooked. Two years after earning his Ph.D., he accepted a position with the FBI. "This is my dream job," he says. "I never could have asked for anything else."

Crime scene investigation

Donna Krouskup ('11) found her dream job as the lead crime scene investigator for the Denton Police Department. She responds to crimes, processes scenes and provides court testimony on analysis and examination of evidence. As an investigator in a city the size of Denton, Krouskup is able to perfect her skills in several areas of forensic investigations.

Donna Krouskup ('11) found her dream job as the lead crime scene investigator for the Denton Police Department. She responds to crimes, processes scenes and provides court testimony on analysis and examination of evidence. As an investigator in a city the size of Denton, Krouskup is able to perfect her skills in several areas of forensic investigations.

"I get to wear a lot of hats," she says. "I process scenes myself in the field and come back to the lab to analyze everything. I work with blood analysis, firearms, fingerprints and footwear impressions." She also trains police officers, detectives, firefighters and other first responders on crime scene awareness and best practices for preserving evidence.

Krouskup earned her chemistry degree while raising her family and working full time as a Denton Police Department dispatcher. As a student, she worked closely with Teresa Golden, professor and director of UNT's forensic science program, and helped launch UNT's Forensic Science Club. She landed her job with the Denton Police Department before graduation.

Golden has since sponsored Krouskup for membership in the American Association of Forensic Sciences. And Krouskup is giving back by offering students internship opportunities in her office.

"Dr. Golden is a great mentor and will always be part of my professional network," she says.

International consulting

William Watson ('98 M.S., '10 Ph.D.) began his forensics career at the Dallas Medical Examiner's office and Southwest Institute of Forensic Sciences in the early 1990s as a forensic DNA technician. While working on his master's degree at UNT, he became a forensic DNA analyst and latent fingerprint examiner at the Fort Worth Police Department criminalistics laboratory.

William Watson ('98 M.S., '10 Ph.D.) began his forensics career at the Dallas Medical Examiner's office and Southwest Institute of Forensic Sciences in the early 1990s as a forensic DNA technician. While working on his master's degree at UNT, he became a forensic DNA analyst and latent fingerprint examiner at the Fort Worth Police Department criminalistics laboratory.

"My major professor, Dr. Benjamin, was instrumental in my success," he says, "because he was willing to allow me the flexibility to work on both of my degrees while working in the field."

After earning his master's, Watson was a laboratory supervisor for Orchid Cellmark in Dallas and later became the director of its Nashville lab. He focused on developing automated DNA analysis techniques, laboratory accreditation and mtDNA sequencing while finishing his doctorate.

Today, Watson is a Tennessee-based forensic science consultant who travels the world to provide expert testimony in court cases and consult on forensic accreditation, laboratory quality assurance and more.

"UNT gave me a solid mix of classroom and laboratory experience that has been invaluable to grow my career in the forensics field," he says.

Stewart says it's a field that continues to grow as science evolves.

"Investigators will always need DNA, and new technology advances help us all find evidence easier and faster."