As a UNT student, Emily Wiskera ('11, '14 M.A.) was enthralled when she spotted a group of preschoolers on a field trip to the Dallas Museum of Art.

The children were focused and intent, acting out scenes of impressionist paintings and enthusiastically participating in discussions.

"Just seeing how the kids were connected to the art -- that was the magic moment for me," she says. "What is that job? How do I do that?"

Wiskera now has that job. As manager of access programs at the DMA, she oversees programming for those with special needs, including those with autism, dementia, Parkinson's disease and vision impairment.

She and other staff members at Dallas-Fort Worth's world-renowned art museums are using the knowledge they gained from the College of Visual Arts and Design's museum education program to develop initiatives that allow visitors from a variety of backgrounds -- including youth, those suffering from memory loss, people from underserved neighborhoods and medical professionals -- to understand the art.

"Our programs are focused on having fun with art and celebrating our own experiences that we bring to the table," Wiskera says.

After she graduated with her bachelor's degree in French and German, Wiskera volunteered at the Bayless-Selby House Museum in Denton. She liked it so much that she wanted to work full-time at a museum and began pursuing her master's in art history, where a museum education class took her on that field trip to the DMA. She later interned at the DMA and began working there in 2016.

She creates lessons so that works of art remind visitors of their personal experiences or culture rather than basic facts such as the date the art was made. She also works with specialists to design the format and resources to best fit the needs of the audiences.

For the painting Mountain Landscape with Approaching Storm by Claude-Joseph Vernet, Wiskera asks visitors what they notice about the painting -- such as being outside and caught in a storm, and what that experience feels and smells like. She'll pass along a thunder tube or rain sticks so the group can make a rainstorm together. The visitors can sniff a scent jar that bears an after-rain smell. The group then creates an art project. Those with autism craft their own rainsticks, while those with dementia paint a basic landscape template with different types of weather.

The job can be sad sometimes, Wiskera says, such as when she discovers that participants with dementia have passed away.

"It is a great honor to be a part of the final chapter of their lives," she says.

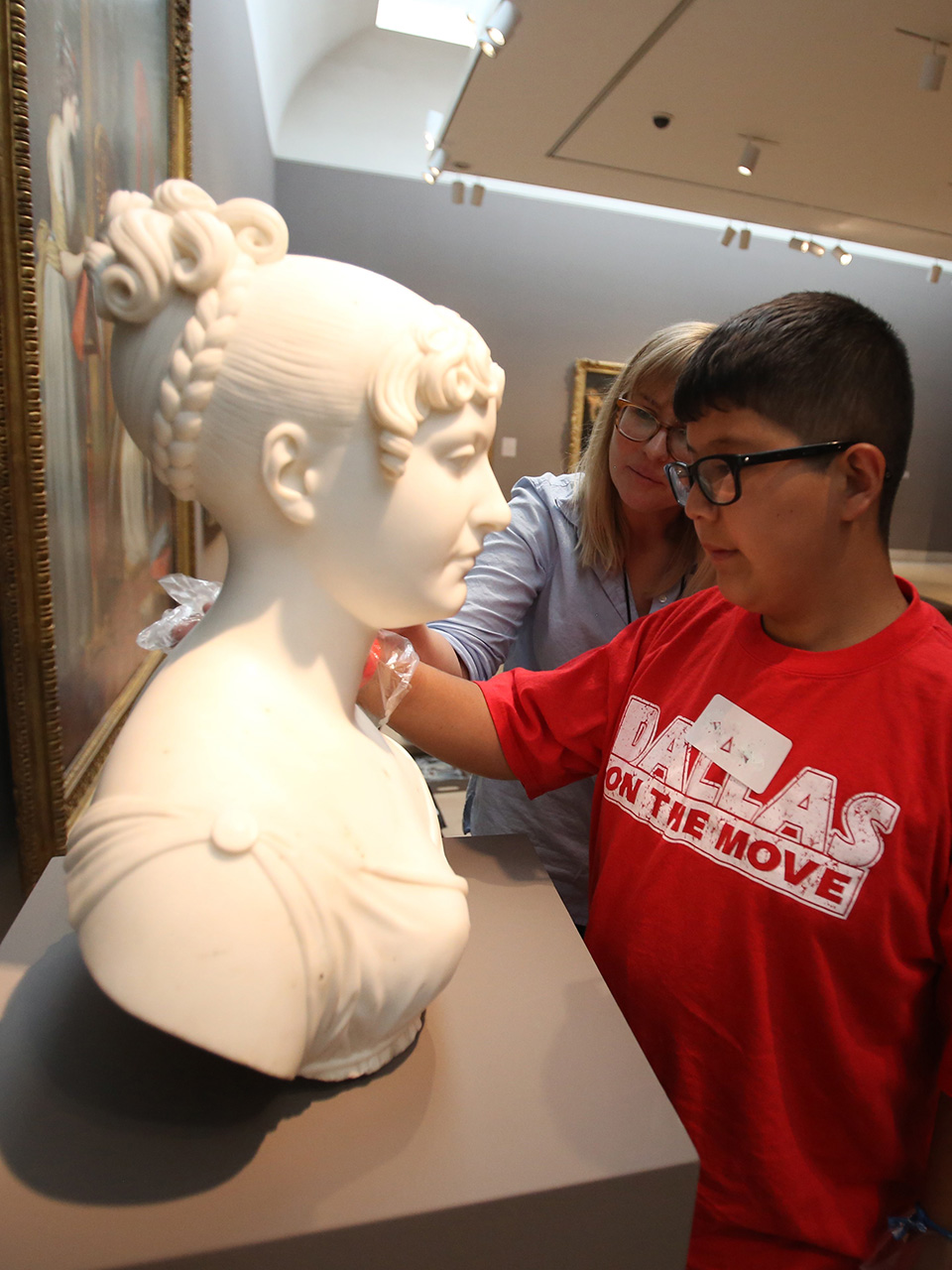

But the job also brings great joy. One of her favorite parts is a program for Dallas ISD students with vision impairments in which they interact with real works of art deemed safe for touch.

"I love those kids -- they're so fun," she says. "They always make me see art in a different way."

At the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, Jessica Fuentes ('13 M.A.) shows students the abstract relief sculpture by George Morrison called New England Landscape II. She says she gets all manner of responses.

One student thought it looked like the floor at McDonald's because of its gray color and its weave-like blocks. Another successfully guessed it was made of driftwood.

Fuentes thrives on those kinds of reactions. As manager of school and community outreach at the museum, she oversees the school tours and develops community outreach programs to bring art experiences to youth.

For community outreach, her team talks about different works of art -- such as New England Landscape II -- at Fort Worth elementary and middle school after-school programs and lead students in creating their own pieces.

For school tours, she reviews the lessons written by her team of educators and helps shape the overall curriculum and teaching strategies. For instance, fourth-grade students are preparing for the State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness (STAAR) writing test, so gallery teachers assign them create a sensory poem describing Ranchos Church, New Mexico by Georgia O'Keeffe.

Fuentes was inspired to go into this field when, after graduating from the University of Texas at Dallas, she interned at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. She loved watching the hordes of schoolchildren as they toured the museum and made their own art.

"I never saw an art museum alive like that," she says. "I knew I wanted to do the same kind of work and bring it to my hometown."

She taught at Van Alstyne and Fort Worth ISDs before working at the DMA and Amon Carter.

During her first outreach last summer, a young Hispanic girl told her, "You work at an art museum? That's really cool."

"For communities of color and other minority communities, representation is so important,” Fuentes says. “By showing works of art by diverse artists, telling diverse stories and having diverse staff, we can help kids see themselves in museums. Maybe that young girl has seen a career path for herself that she might not have imagined before.”

Like Fuentes, Amanda Blake ('06 M.A.) wants to reach out to those who may not visit museums.

"Thinking outside the walls of the museum is important to us," she says.

As director of education and library services at Amon Carter since 2018, Blake provides the leadership, strategic direction and vision for the museum’s education department as well as its research library, both of which are fundamentals of the institution’s mission.

During this time of renovation projects at the museum, Blake is making space for new audiences and unexpected perspectives with a shift toward community and social practice.

“Embracing networks of people and new communities, enhancing collaboration, and advancing empathy and creativity allow us to present the museum, its collection and its exhibitions in a way that establishes dialogue and opportunities for creativity, reflection and meaningful connections,” Blake says.

Blake and Madeline Fitzgerald ('13 M.A.), manager of adult programs, are retooling the museum’s offerings for adults to connect with artwork in a fun way, geared to younger audiences. They also are expanding programming for families at the museum.

Blake and Fuentes focus on specific zip codes, such as the Northside neighborhood in Fort Worth, and attend festivals and other events to create awareness and introduce new audiences to the museum.

Blake also is reaching out to another untapped audience -- medical professionals. They’ve initiated a program with JPS Hospital, the Modern Art Museum and the Kimbell Art Museum to strengthen the observation and communications skills of physicians, nurses and hospital residents. The medical professionals participate in a variety of gallery activities with works of art at all three Fort Worth art museums that are designed for group engagement and discussion.

“A nurse may notice something a doctor wouldn’t, and being in a museum space together can enhance group dynamics when the professionals are working together back at their hospital,” Blake says.

Blake has relished seeing those “aha” moments throughout her career. After she graduated from Oklahoma State University, she worked as the education project manager at the Wichita Art Museum for a year and a half. While pursuing her graduate degree at UNT, she interned at the Nasher Sculpture Center, then landed a job at the Dallas Museum of Art after graduation in 2006. She started working with family programs and then was head of family, access and school experiences.

It was during that time that she had one of her most rewarding experiences. She had created the Meaningful Moments program for those with Alzheimer’s and their caregivers. During one session, the group discussed a painting depicting an apple tree, and one participant told his wife about an incident during his childhood -- an apple truck turned over in his neighborhood, and the community made applesauce and apple pie from the apples for an entire summer. His wife had never heard him speak about that in their 50 years of marriage.

“Moments like this attest to the power of art, not only in sparking memories and creating conversations, but in strengthening connections and social bonds,” Blake says. “That’s why I love my job.”