Amy Schade ('13) never had much interest in science growing up. Truthfully, she didn't exactly know what a scientist did.

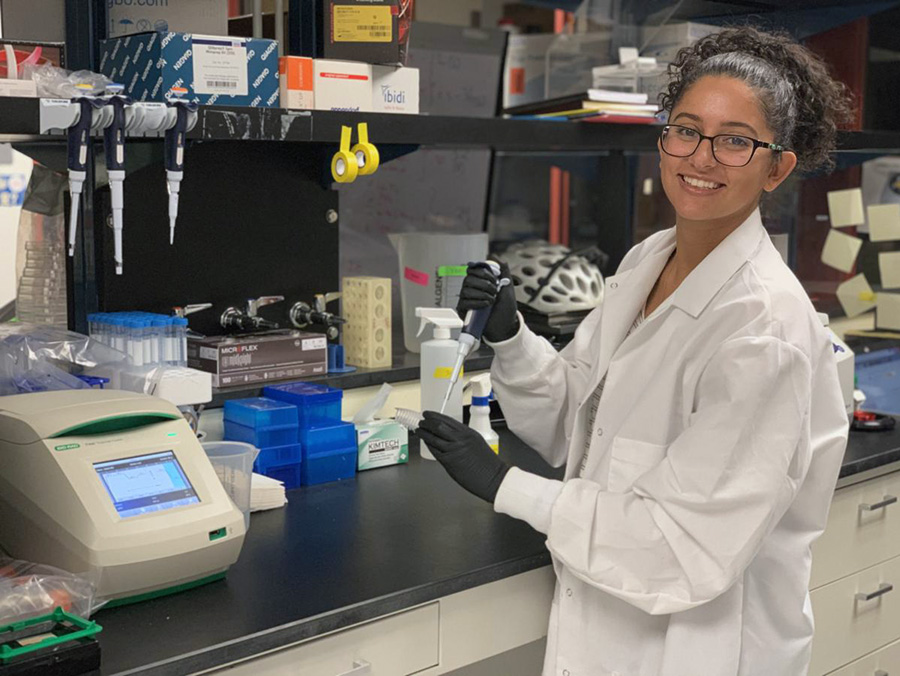

Now a postdoctoral research fellow at Boston-based Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, where she studies triple-negative breast cancer, Schade can fervently describe the inner workings of a human cell and has long outgrown the notion that scientists always know the outcome of the experiment before it happens.

Actually, a freshman biology class at UNT changed that view -- and really, her whole outlook on science.

Recruited from Grapevine High School to the UNT Debate Team, Schade had every intention to major in history and become a high school teacher. At freshman orientation, when it came time to separate into majors, she decided on a whim to join the biology majors instead. There, she listened to Lee Hughes, associate professor of microbiology, talk about a laboratory that gave undergraduates a chance to discover new viruses. That prospect of finding something never seen before intrigued Schade to register for the lab.

While taking the introductory course in the UNT Phage Hunters Advancing Genomics and Evolutionary Science (PHAGES) program, Schade did unearth from soil a type of virus, known as a bacteriophage,that infects bacteria. Her findings, and the work of other students,were sent to the National Center for Biotechnology Information to be published in its GenBank database, a publicly available online resource of nucleotide sequences for more than 300,000 organisms.

"It was pretty quick into the first semester, I realized that research was what I wanted to do," says Schade, who eventually majored in biology. "That sense of discovery and ownership from what I had contributed to our understanding of bacteriophages, that was really empowering and exciting for me."

More than 500 students have been touched by the undergraduate research experience since 2009, when UNT became the first university in Texas to offer the classes as part of the national Science Education Alliance-Phage Hunters Advancing Genomics and Evolutionary Science (SEA-PHAGES) program,sponsored by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. While the program was developed to inspire interest and retention in the science, technology,engineering and math disciplines, Hughes, who is director of the UNTPHAGES program, sees value even for those venturing beyond STEM.

"Some of the students from the first couple of years ended up being business majors or music majors or something totally different, but they still learned a lot about the science and it was a positive experience for them," Hughes says. "I think overall, students appreciate it even though they aren't interested in research. But then you have students who didn't even know research was a career option."

The biology course led Isabel Delwel ('18) down a path in the sciences. Following her participation in the PHAGES program, she took part in the prestigious Ronald E. McNair Scholars Program, was selected as one of 67 students in the U.S. for the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Exceptional Research Opportunities Program, spent a summer in Seattle working at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research and became a full-time researcher at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Recently, she started a Ph.D. in microbiology and immunology at Stanford University.

"The PHAGES program really gave me exactly what it's supposed to -- a good introduction into research. I got to see one small, full circle about how research could be integrated into adding knowledge to science," Delwel says.

From the beginning, Hughes and his former PHAGES co-director Bob Benjamin wanted to give undergraduates an opportunity to participate in research from day one of their college career, plus introduce them to the scientific way of thinking in a project that leads to real science data rather than a cookbook experiment where the professor tells you the result.

"If it fails and things don't work, they have to try it again,"Hughes says. "They learn to troubleshoot their work. It's all the things a real scientist does."

Freshman Jack Laub-Tracy learned the art of trial and error and patience last fall in the PHAGES program. Nearly a month into the class,Laub-Tracy still hadn't isolated a virus from the soil he collected.

"You think it should be easy to find something that's everywhere," he says. "I'm determined."

Once students do find a virus from their soil sample, they must purify it in order to extract its DNA.

At the end of the first semester, Hughes sends some bacteriophages for DNA sequencing. Students then spend the entirety of the second semester studying all the genes in the viruses using a variety of methods from biology, computer science, information engineering,mathematics and statistics known as bioinformatics to interpret the data.

The resulting DNA sequencing annotation for the bacteriophages are uploaded to GenBank, giving students authorship on a scientific resource. Some students also become co-authors on research papers that use data collected from the PHAGES program, including a 2015 paper published in the journal eLife that chronicles all the findings up to that point from UNT and the dozens of other schools that participate in the program.

To date, UNT students have added 508 bacteriophages to the SEA-PHAGES database, and 136 of those also have been published in the international GenBank database.

For those students wanting to take an even deeper dive intobacteriophages, Hughes selects four to six undergraduates each semester to build upon the work from the biology classes in his lab.

Senior and PHAGES alum Brendan Frederick has been working in Hughes' lab to further study bacteriophages identified in the course.

"A lot of the stuff we did in the lab, it's ended up following me in my upper level courses," Frederick says. "I'm still learning a lot from the research I did and am continuing to do."

Both Schade and Delwel also spent time working in Hughes lab while at UNT. Now, they both dream of starting their own labs where they can inspire the next generation of researchers.

"Aside from the science, Dr. Hughes showed me that you have the power to guide someone to where they want to go," Delwel says. "That was influential for me. I want to help provide opportunity and access to others through my own lab."