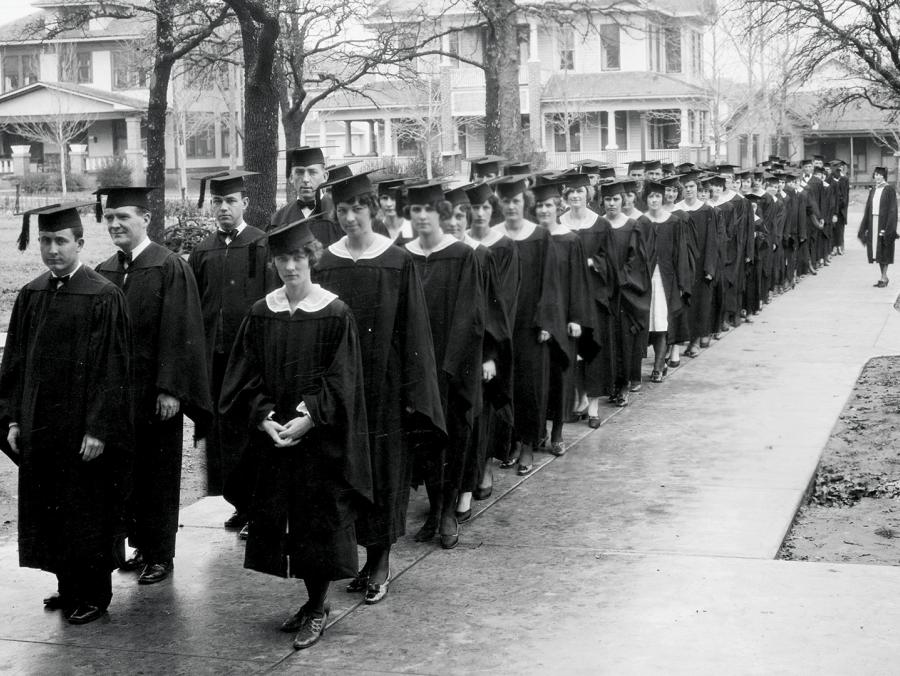

Arts and crafts have seen a surge in popularity this year as the pandemic has forced many to spend more time at home. But that’s not unprecedented, according to art historian Jennifer Way, a professor in UNT’s College of Visual Arts and Design. People have used craft as a means for therapy and wellness, cultural heritage and political activism in periods of conflict throughout history.

How do you define craft? How is it different than other art forms?

I define craft by trying to understand how discourses or sets of meanings that are specific to a time, place and social group constitute what counts as its forms and practices. For many Americans, craft is a cultural form that emerged in the U.S. during the 19th century as a hand-based fabrication valued especially for its differences from machine-made goods. Before then, craft comprised the creation, materials, histories and uses of many objects of everyday life.

Are there certain types of crafts that were common in different time periods?

Favored crafts during World War I included basketry, weaving, jewelry and metalsmithing. During World War II, crafts shifted to more natural materials and plastic materials (and their combinations) that facilitated fluid, abstract forms. The embrace of machine technology for precision and replication, and an interest in re-use of materials developed through the end of the 20th century.

Can you talk about your upcoming book, Deploying Craft: Crafting Wellness and Healing in Contexts of War?

I am looking at why and how Americans made craft for therapeutic purposes comprising wellness, coping and rehabilitation from trauma and injury in relation to WWI, WWII, the Global War on Terror and COVID-19. I am also interested in the ways that making craft for these purposes related to the art world’s ideas about craft.