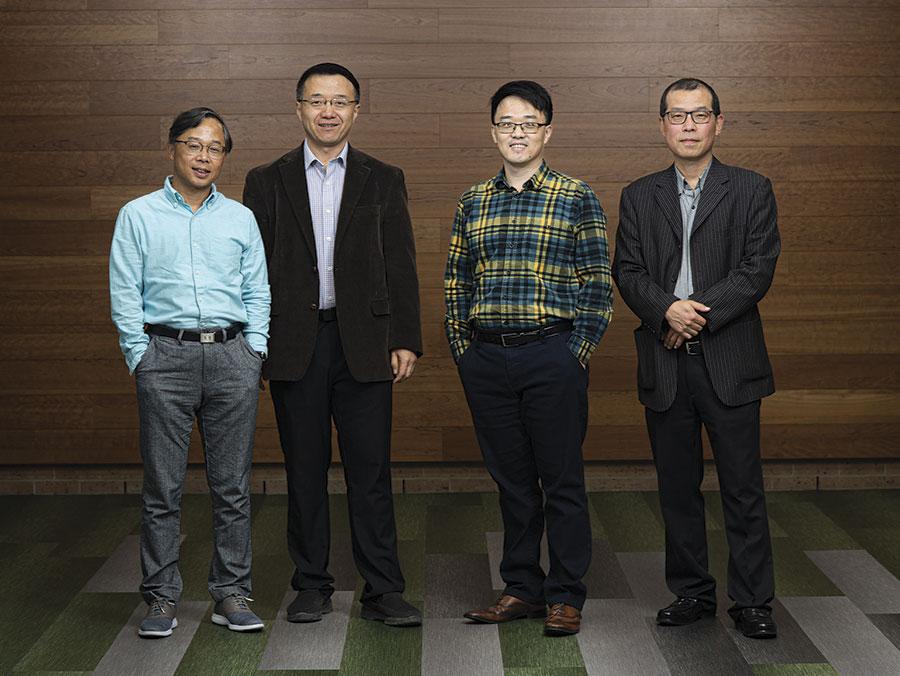

On a chilly April night, a group of UNT students enter the Bridgeport Correctional Center.

They line up to sign in and get badges before they are patted down by correctional officers and walk through the metal detector.

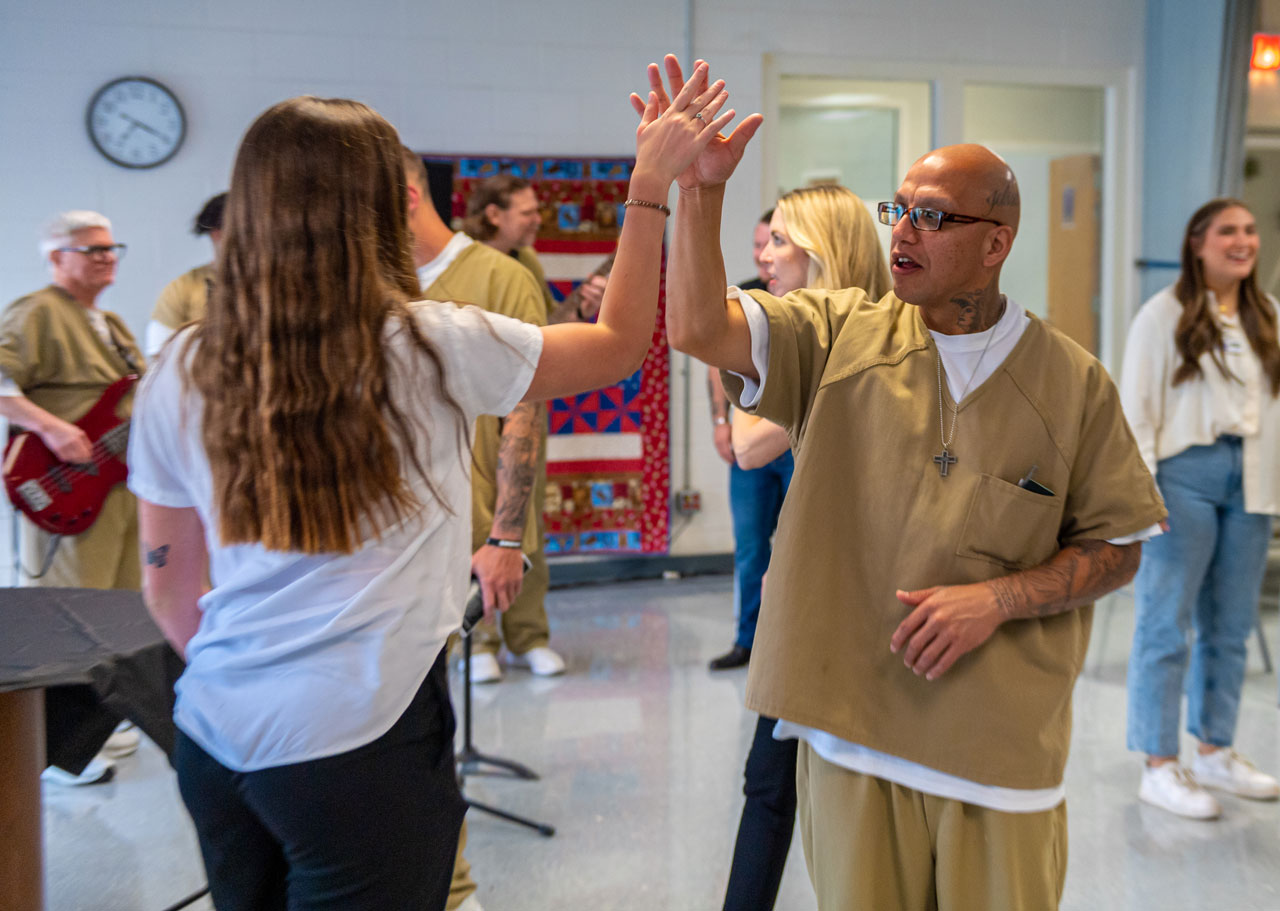

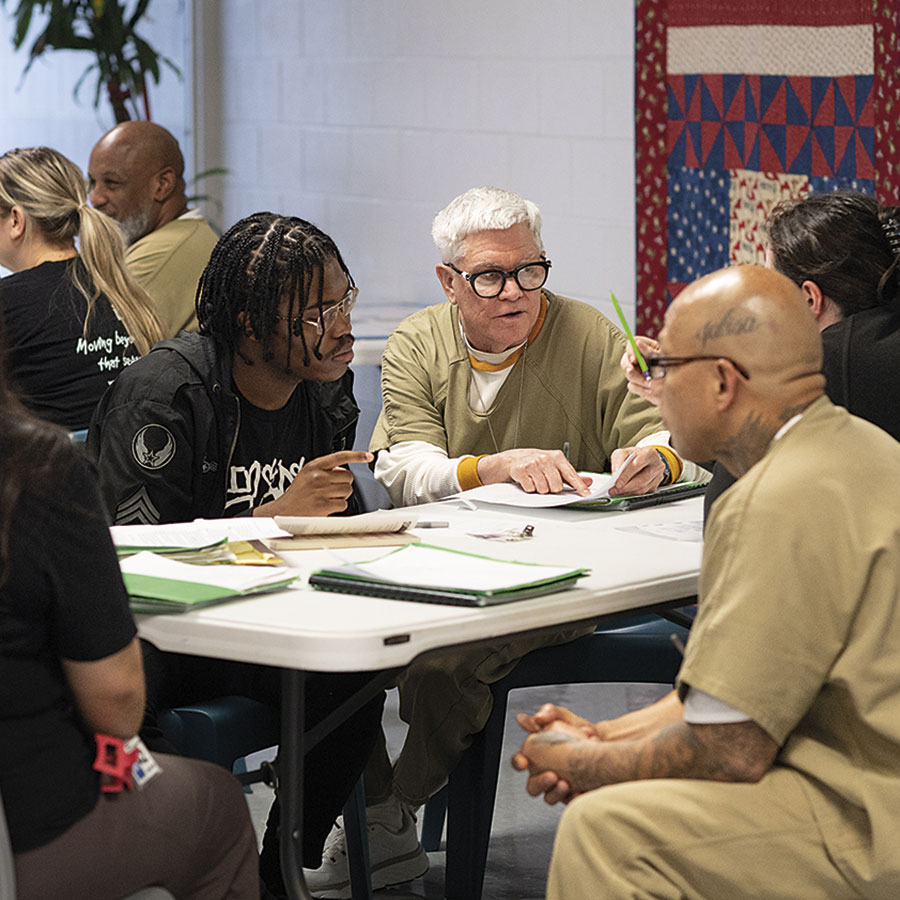

After they wait in the hallway for clearance, they enter the program hall and greet classmates dressed in regulation beige uniforms -- shaking hands with them before the three-hour class starts.

The class is part of the Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program, in which students from UNT attend class with the incarcerated people in the minimum-security prison each week. Led by Haley Zettler ('09 M.S.), associate professor of criminal justice, the UNT students have discovered more about the workings of their future professions and the inside students say they have a new sense of value and purpose.

"It's more than you can expect as an instructor," Zettler says. "For some people, it can really mean a shift in how they see themselves."

Jose, an inside student with a talkative, friendly manner, says he feels sad when he sees the clock ticking down to when the class ends. "It's the highlight of my week," he says. "I'll be honest, I enjoy feeling like a regular person. The system -- they dehumanize you. To me, it's a joy working with people who make me feel good."

On the first day of class, things are usually awkward. The students sit in a circle and participate in a "wagon wheel" -- an icebreaker in which they complete a sentence about themselves, such as "My superpower would be …" Every time, Zettler thinks it won't work. By the second rotation, everyone is laughing at each other's answers.

"This goes from uncomfortable anxiety to, ‘Oh my gosh, this is going to be amazing,'" she says. Zettler, a former probation officer for Denton County who earned her master's in criminal justice at UNT, read an NPR article about Inside-Out, which began at Temple University and has 150 participating institutions across the country. The program was the first of its kind in the state of Texas and has reached prisons around the world.

Zettler notes that education can reduce recidivism and improve outcomes for incarcerated people when they are released from prison. She first led the program when she taught at the University of Memphis, and she saw how it helped students understand the justice system from another angle. When she interviewed at UNT, she told the hiring committee she wanted to bring Inside-Out to their criminal justice students. After delays due to COVID-19, the program was implemented in fall 2022.

The inside students must have a high school diploma or GED, no major disciplinary infractions and a projected release date after the class ends. Zettler interviews them before they are accepted. "We stay away from what they did," Zettler says, adding that they never know what crime the inside students committed.

They meet in a program hall with its white walls, patriotic murals and row of vending machines. It looks like any other meeting place except for a wired enclosure outside the window.

During the sessions, the students pass around a small stuffed animal -- Lucky the albino squirrel, UNT's legendary good luck charm -- that designates when it is a student's turn to speak as they sit in a circle, alternating between inside and outside students.

Each week focuses on a different topic, with an interactive or scenario-based project. One week, they discuss the many parts of the criminal justice system, exploring each organization's mission statement and goals. They talk about restorative justice and victimization. They take part in a reentry simulation, in which they perform a task every 10 minutes, representing a week, for an hour and a half. Tasks include getting their birth certificates and identification and Social Security cards, finding a job, paying rent, getting transportation, working, reporting to a parole officer, taking drug tests and applying for public benefits.

The inside students, many of whom don't have visitors or family who see them, receive a report card and certificate upon completion of the class. One inside student was so proud of his certificate that he had his girlfriend take it with her because he didn't want it to get damaged.

Zettler received an email from another girlfriend of an inside student about how much the graduation ceremony meant to them both. As part of the event, the couple got to eat their first meal together in 30 years. "I started, like, bawling," Zettler says. "This is why we're doing this."

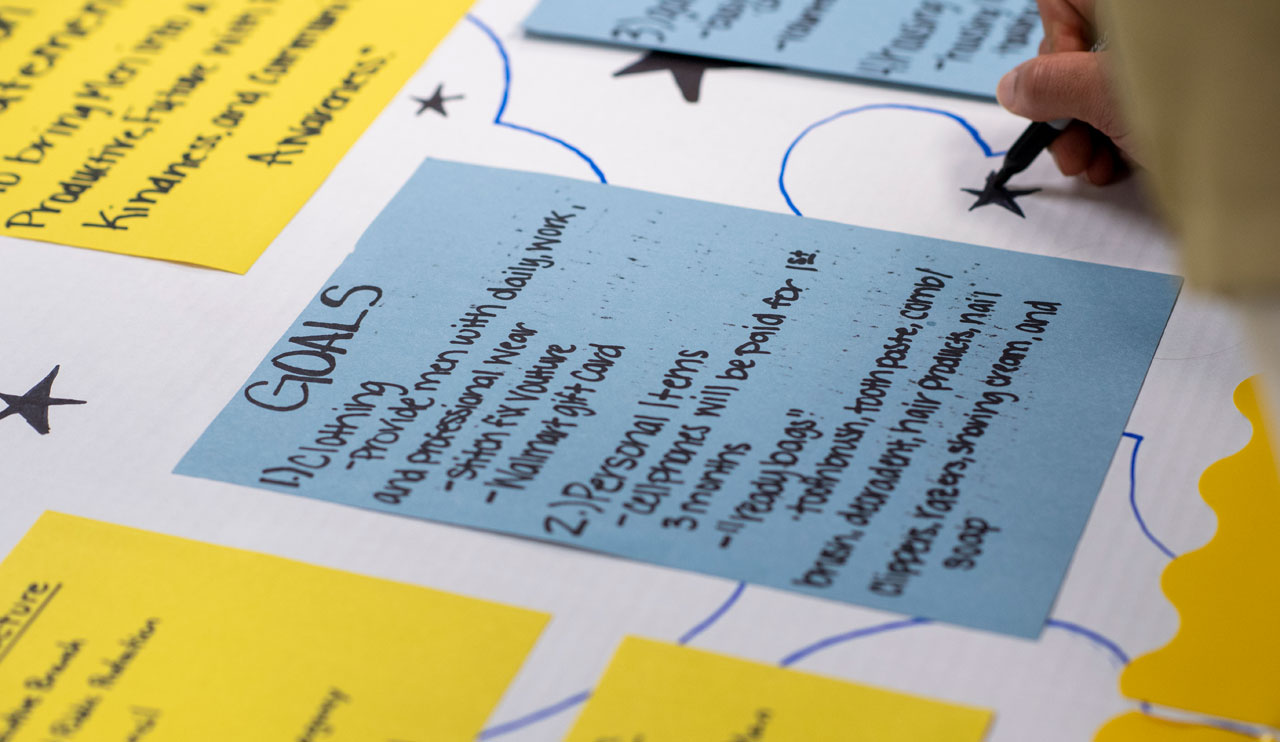

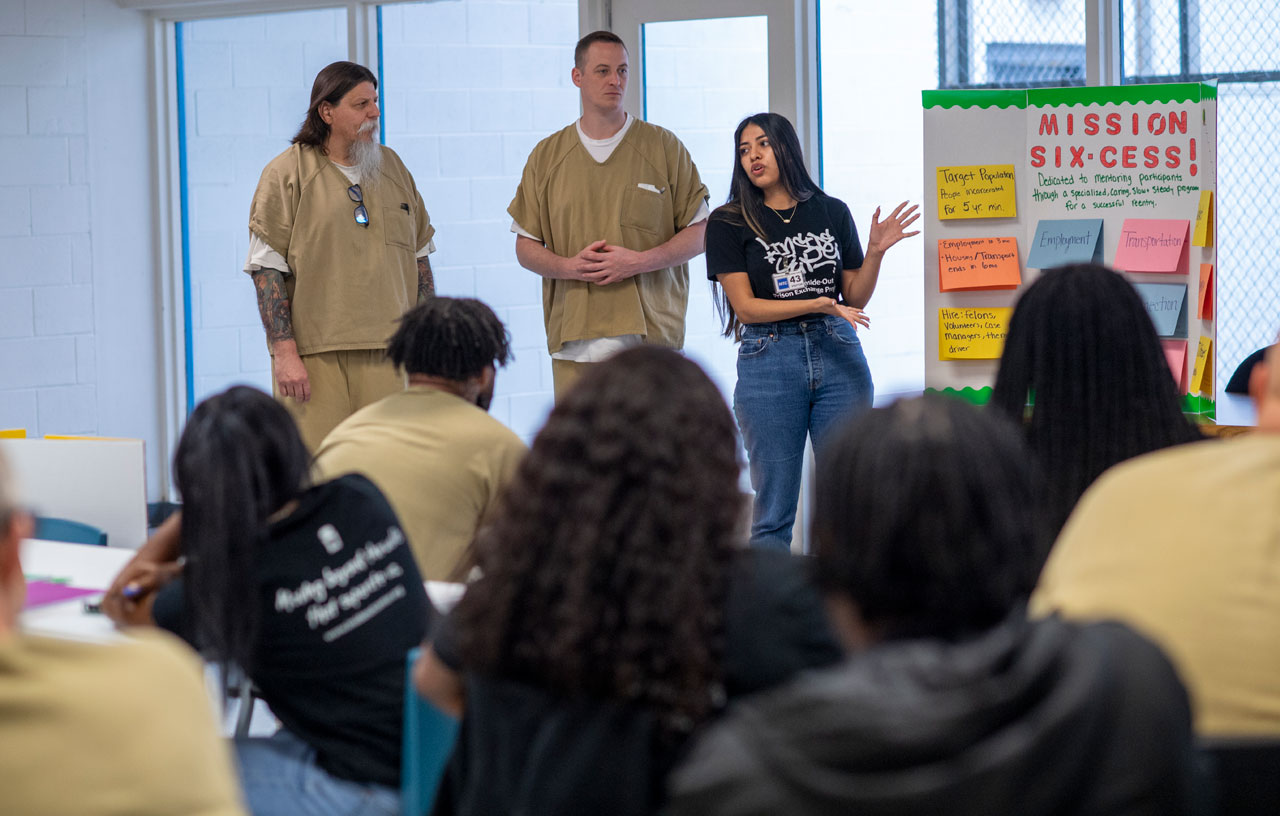

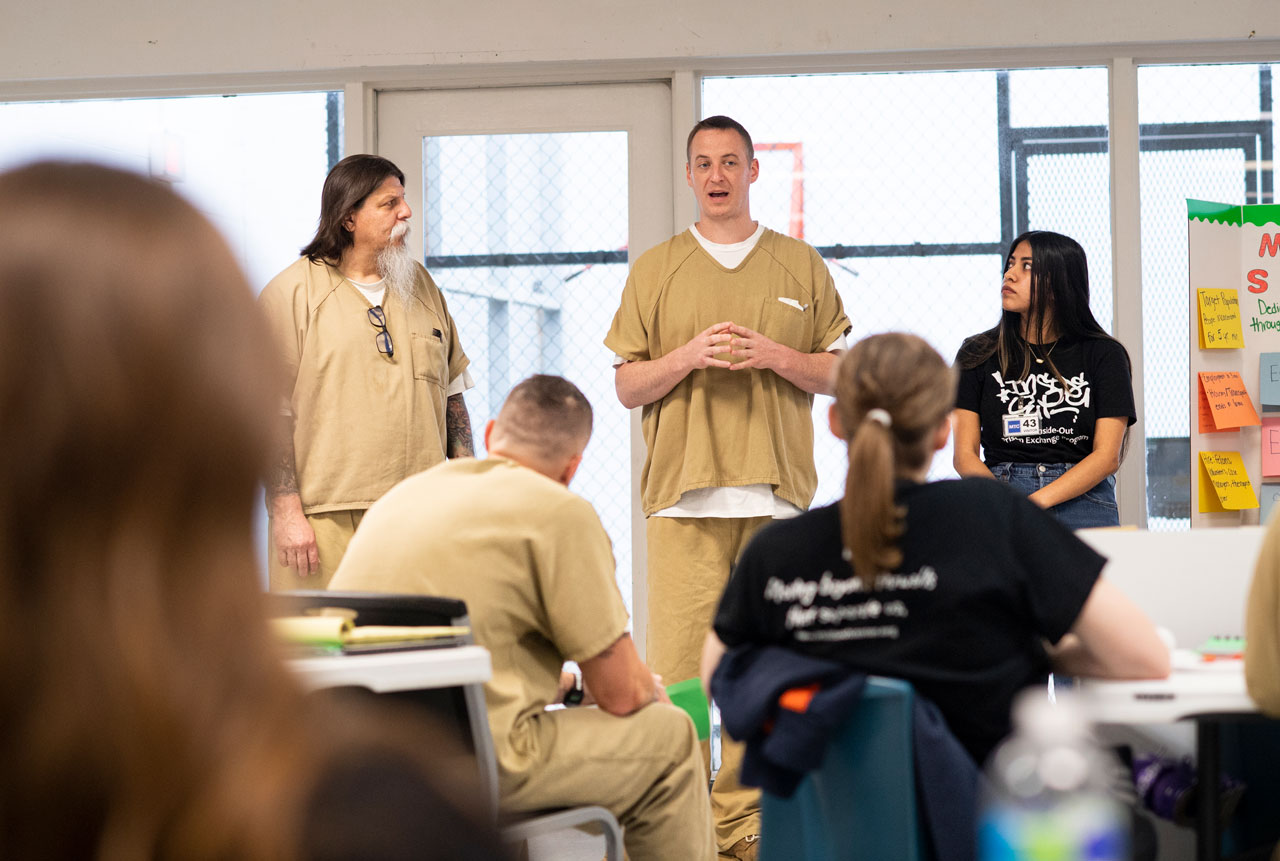

For three weeks, the students separated into groups to work on their ideas for a reentry program. Tonight, they will give their presentations while a Shark Tank-style group of judges chooses the best one.

The groups outline their ideas -- featured on a posterboard -- for a program that would help incarcerated people make the adjustment to living on their own. They offer car services, insurance and other stipends. One group recommends the online clothing service Stitch Fix, since incarcerated people won't have any clothes and it's hard for them to travel, and a "ready bag" filled with items such as shampoo and a razor.

They address gaps, such as pairing them with mentors since many lack connections and may fall back into old bad habits. Many suggest mental health and wellness programs, and other ways to assist them with technology.

After each presentation, other inside and outside students raise their hands and grill them with questions. Zettler questions one group about their high budget. "I like your optimism, it's just the realities," she says.

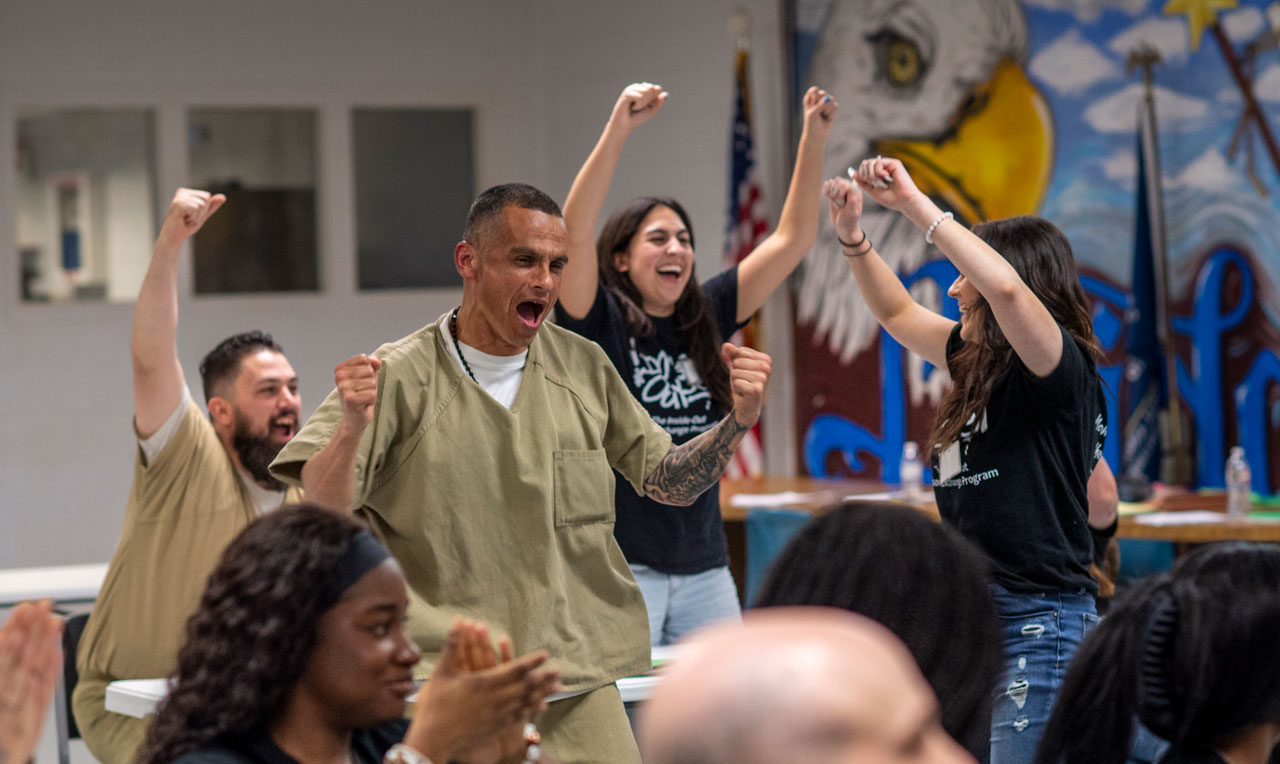

When the judges are ready to announce the winner, the students all drum their tables. The winner is team Revive 365, which dreamed of big corporate partners and provided bus passes and wellness services for a smooth transition into society.

Sarah, a senior sociology major, says they won because they talked about funding. But Jose likes to give himself credit. "We had really good speakers," he says. "I got that commanding, very powerful voice."

It's these types of sessions that teach the UNT students what their future careers could be like. Alexis ('23), a criminal justice major, says she was nervous at first, but the inside students became her friends. "I became very proud of the major I chose," Alexis says, noting it allows her to focus on meaningful issues. "They tell us, ‘You can advocate for us.'"

Haley, a junior criminal justice major who wants to be a police officer, says the program made her see different viewpoints. "I think how easy it is to end up in jail," she says, but as an officer she would "take an extra second and think."

Jeff, an inside student with a long white beard, says he learned about restorative justice. "I know I want to give back to the community, and it made me realize how much I took for granted." Working with the students, he says, "I felt more of a human."

A week later, a long table is lined up with chicken fingers, tamales, sheet cake with green frosting, cookies and gallons of tea and lemonade. It's graduation night.

The presentation begins with inside students Antwan and Tom performing a song Tom wrote, "Story's Told." "It allowed me to think about our books, our chapters," Tom tells the crowd before he sings, "It's not what you have, it's who you got, a chapter of healing from inside out/From the inside out, the story's told."

During the ceremony, a group of inside and outside students speak about their experiences. Deanna remembers her first time driving to the prison. "I was kind of terrified, reading all those rules," she says. But she recalls the fun conversations she had with others.

"I never expected to leave the building talking about tarot cards and palm reading," she says. "I was never afraid to be myself. This class forces you to look at vices you hold yourself."

Joseph, an inside student, notes that one student, Raji ('23), has been accepted to Georgetown Law School and another, Sarah, wants to work in mental health. "I hope that you keep helping make the system better," he says.

Taylor, a junior criminal justice major, says she would always get a negative reaction when she told friends she wanted to be a defense attorney. "To the inside guys," she says, "I don't have to search for the good. It's right there in front of me." She begins tearing up as she addresses the individual inside students and their attributes -- Jeff and his warm smile; Will, who says crickets taste like popcorn. The inside students tell the outside students their favorite songs, the dogs they want when they get out and what their lives will look like.

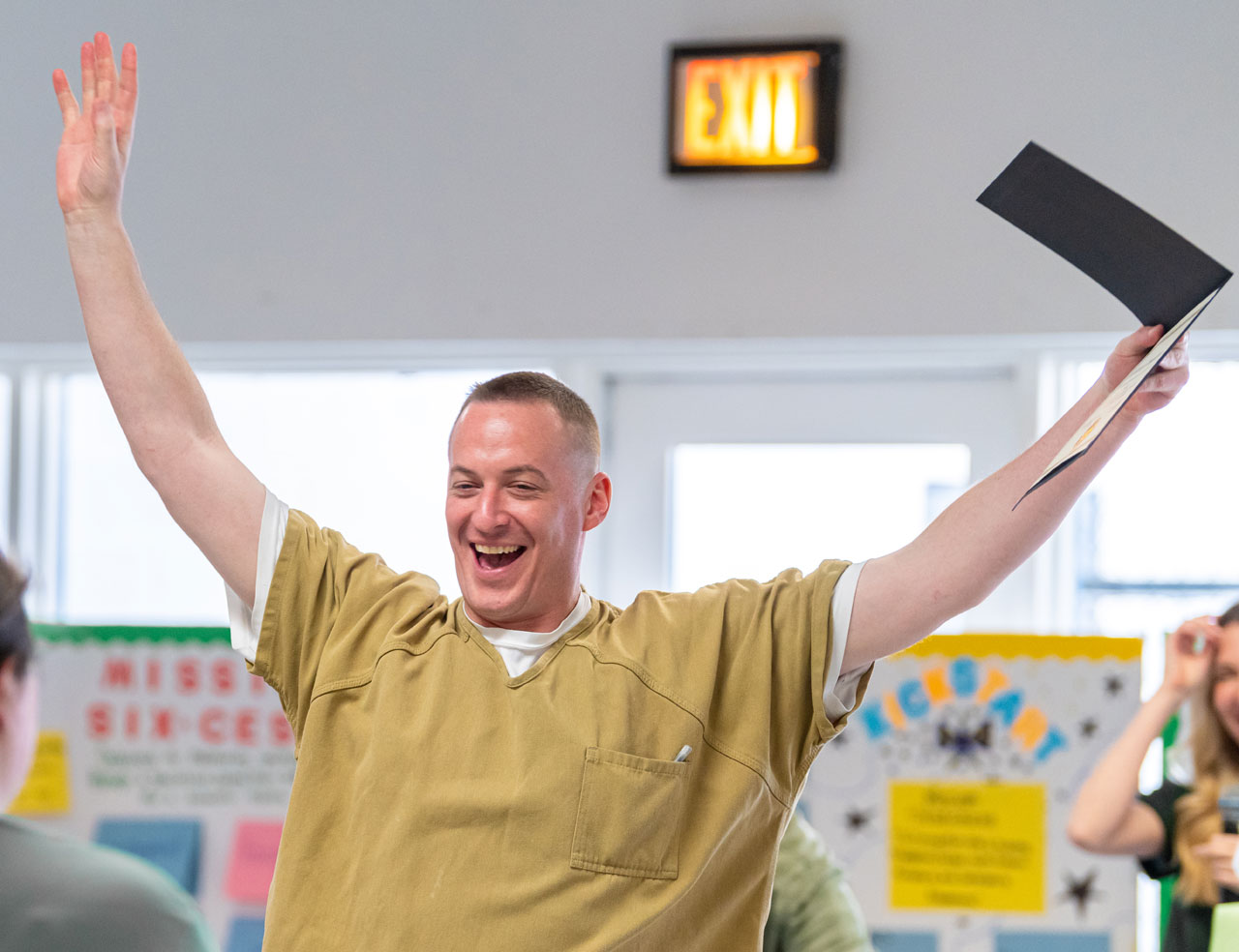

The chaplain presents the certificates, which are enclosed in a black folder. One inside student grabs a tissue after accepting a certificate. Jose raises his arm, "Yeah!" Will struts up to get his certificate with a big grin on his face. "Obviously, our class clown," Zettler says.

Zettler then speaks, noting the change from the palpable tension on the first day to the friendliness of the last day. "It has reinforced my beliefs in the power of education," she says.

The ceremony ends with inside students Antwan and Deryl singing, and then the class members eat together with their guests. After the guests leave, the students gather together for one last wagon wheel. "That's how they met, that's how they say goodbye," Zettler says. "This time it was filled with tears. It comes full circle."

They know they will likely never see each other again. The inside students return to their cells. The UNT students rejoin the world.

Watch Associate Professor of Criminal Justice Haley Zettler (’09 M.S.) discuss the possible connections between childhood trauma and substance use in justice-impacted populations as part of UNT’s The Lab series.