As an undergraduate at UNT, Jody Huddleston (’10) found something strange in the HIV research she was conducting for Joseph Oppong’s medical geography class.

As an undergraduate at UNT, Jody Huddleston (’10) found something strange in the HIV research she was conducting for Joseph Oppong’s medical geography class.

When she took her questions to Oppong, professor of geography, he says he thought to himself, “This is someone who will do fine work.”

His instincts were right. Huddleston, who was in the Honors College and was a McNair Scholar, found out she was seeing “late testers” —individuals who had little time between their HIV diagnosis and the onset of AIDS. With Oppong’s help and encouragement, she set up a project to map this specific group across the state, determining characteristics and areas with high rates of late testers.

The work earned her a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, worth $42,000 a year for three years. She is using the fellowship as a doctoral student in environmental science at UNT, studying diseases with an environmental component.

Other faculty members also are investing their care, experience and knowledge in students to help them achieve their goals. UNT leads Texas universities in the number of Barry M. Goldwater Scholars, and many talented students place as semifinalists and finalists in the prestigious Siemens Competition and Intel Science Talent Search. Faculty members also guide students to win prestigious awards such as the Rotary Foundation Ambassadorial Scholarship and the German Academic Exchange Service scholarship.

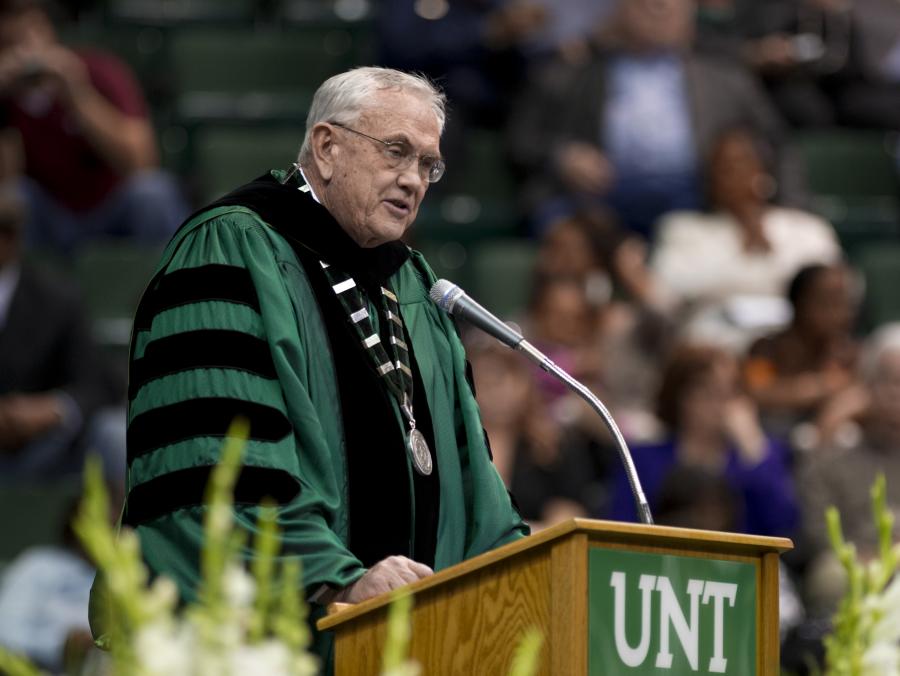

Your mentors

Mentors host regular meetings and ongoing discussions so that the students are best prepared. The students also are aided by UNT’s Office for Nationally Competitive Scholarships, which guides them through the application process.

James Duban, the office’s director and professor of English, encourages students to have “something above and beyond to write about in their application essays” by fashioning "ideal college educations," which include research experience. He also provides comprehensive feedback on writing style and tone.

"I urge them to articulate their contributions and goals with clarity, conciseness and authority," he says. "The application process can take several months and often becomes a capstone educational experience.”

The prestigious scholarships can mean thousands of dollars in stipends and tuition and, in some cases, travel to another country. By the time the results are announced, the students have done more than win an important award, says Sandra Spencer, principal lecturer and director of women’s studies.

“You see them become much more professional,” says Spencer, whose students have won Rotary scholarships, among other awards

“You see them become more aware of a wider world.”

Looking for that spark

Just like Oppong saw the promise in Huddleston, Spencer can spot potential scholarship recipients.

Just like Oppong saw the promise in Huddleston, Spencer can spot potential scholarship recipients.

“Sometimes it’s a little spark you see in them,” she says, “They’re well-rounded in a intellectual, emotional and cultural way.”

A UNT faculty member since 1996, Spencer has accompanied students on Study Abroad programs and to various events. She says potential scholarship students are more likely to be engaged at a different level. She notices if they can thrive abroad or if they have the mind to be challenged for a globally-focused project.

She saw that in Christine Schneider and Maryanne Owiti, master’s students in interdisciplinary studies, who attended the Commission on the Status of Women practicum this spring at the United Nations headquarters in New York City.

They were among 20 women who observed non-government organization sessions on gender equality and other women’s issues and then created an advocacy project when they returned home.

“UNT was the only school that had more than one student at this event, and that is a direct result of Dr. Spencer's engagement and encouragement in developing our passions and interests,” Schneider says.

Similarly, Graham Phipps, professor of music, was impressed when Ben Dobbs (’10 M.M.) came to him for advice on his master’s thesis topic.

Similarly, Graham Phipps, professor of music, was impressed when Ben Dobbs (’10 M.M.) came to him for advice on his master’s thesis topic.

Dobbs wanted to find a composer from the early 1600s to study, one who was not well known. After some digging, he chose Heinrich Grimm, who had only a few works published in his lifetime after being exiled from his German town during the 30 Years War. But to research his subject, Dobbs needed to go to the library in Germany that houses Grimm’s works.

“This student had a passion for what he wanted to study,” Phipps says.

Together, they developed a plan and Dobbs received a scholarship from the German Academic Exchange Service, a prestigious program that allows American students to study in Germany for one year. Dobbs is now working on his doctorate in music theory.

Hard work

Finding that spark and helping students apply for scholarships is just one part of the mentoring process. Faculty also support students in the research itself.

Finding that spark and helping students apply for scholarships is just one part of the mentoring process. Faculty also support students in the research itself.

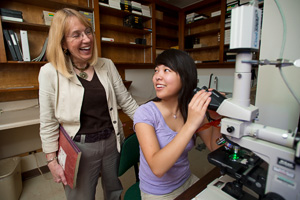

One of the ways Jannon Fuchs, professor of biological sciences, helps is by playing “email ping pong.”

As her students are writing research papers, she responds with comments — sometimes dozens of rounds. But Fuchs notes that she’s critiquing the science, not the person.

“I guess I try to toughen them up,” she says. “It’s valuable training.”

In her 24 years at UNT, Fuchs has worked with students at all levels, including those tackling college courses in UNT’s Texas Academy of Mathematics and Science. The two-year residential program allows talented students to complete their first two years of college while earning their high school diplomas.

Fuchs helps her students prepare to compete for prestigious scholarships. Under her leadership, eight have earned Goldwater Scholarships, given to students pursuing careers in math, science and engineering; 14 have advanced in the Siemens Competition, the nation’s leading original research competition for high school students in math, science and technology; and three have won the Intel Science Talent Search, the oldest science competition in the nation.

One of those TAMS students who plans to enter the Siemens and Intel competitions is Faith Yu. Her neuroscience research involves twice-weekly lab work and computational work. While Yu already had some basics of neuroscience, she says Fuchs gave her a first look at how real research labs work.

“When Dr. Fuchs interviewed me for the lab, she refreshed my neuroscience knowledge and added to it within the span of 30 minutes,” Yu says.

Phipps also moves students to do their best. He meets with them once a week.

“You have to ask them a lot of questions,” he says. “Why did you do this? Does this follow where you were before?”

While Dobbs was in Germany, Phipps emailed him every week.

“What did you find interesting this week?” he asked him. On Dobbs’ drafts, Phipps wrote, “You might think about this.”

Dobbs — who found some unpublished work of Grimm’s and a funeral motet, or choral composition, that became the topic of his thesis — hopes one day to publish modern editions of Grimm’s compositions.

“Dr. Phipps directed me,” Dobbs says, “and pushed me to analyze and look for new ideas.”

Amy Cathleen Hamman (’06 M.A.) had a similar experience when she worked on her master’s in art history under the guidance of Kelly Donahue-Wallace, associate professor of art education and art history.

Amy Cathleen Hamman (’06 M.A.) had a similar experience when she worked on her master’s in art history under the guidance of Kelly Donahue-Wallace, associate professor of art education and art history.

“I was sort of floundering around, wondering how I would ever write a thesis and she was like, ‘OK, this is what we need to do,’” says Hamman, who is working on her doctorate at the University of Arizona. “She helped me formulate a game plan and made sure I stuck to it.”

Rewards

All the hard work results in rewards for the students — and their mentors.

Phipps notes that with such intense study, students don’t just develop as researchers, but also as people.

“It’s always great to see a student mature and see their ideas come to fruition,” he says.

Oppong watched one senior geography major, Jonathan Rodriguez, defend his research at the Association of American Geographers in February in New York City. Rodriguez was questioned by an author whose book on geographic information systems and public health he had cited.

“It was fun to watch a student be challenged and defend himself,” Oppong says. “He was ready.”

Huddleston appreciates the help she received from Oppong because he pushed her to succeed.

“You want someone who is involved with what you are doing and is helping you set goals and meet them,” she says.

And Oppong makes sure the students he mentors have some fun as well. He hosts a graduate appreciation lunch at Bruce Hall and potluck dinners at his house. They become a family — and it’s even more satisfying when that family member wins an award.

“It’s like being a parent,” Oppong says. “And your child has accomplished something great.”