|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

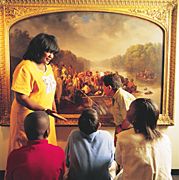

SOME DAYS IT'S NOT POSSIBLE TO SEE the forest for the trees. Or the reflection for the water. At least, that’s what a group of fifth-graders learning the art of thought discovered during a recent trip to the Amon Carter Museum’s Downtown Gallery in Fort Worth. “From a distance the reflection is crisp, but up close you can’t see it at all,” 11-year-old Brittany Thomas said to her teacher as they looked at William T. Ranney’s Marion Crossing the Pedee. “I think the artist wants us to think about that,” she said. So they did. For more than 10 minutes, the students discussed the idea of perspective, how it is used in art and its philosophical translation into everyday life. Brittany and her classmates are participating in one of two key programs that UNT’s School of Visual Arts and its North Texas Institute for Educators on the Visual Arts are conducting in an effort to reform education and elevate the arts in Texas. The first program is a partnership of UNT and six Metroplex schools with five national sites and 30 other schools for a five-year, $15 million national education reform initiative — Transforming Education Through the Arts Challenge. The program is funded primarily by the Walter H. Annenberg Foundation and the J. Paul Getty Trust. The second program — UNT’s Marcus Fellows program — which is funded by the Edward and Betty Marcus Foundation, prepares today’s graduate students to be tomorrow’s art education leaders.

Transforming education In 1996, 36 schools from urban, suburban and rural areas of eight states — California, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Nebraska, Ohio, Tennessee and Texas — were selected to participate in the Challenge program. UNT’s North Texas Institute for Educators on the Visual Arts heads the program in Texas. Six schools are partners with UNT — Mitchell Elementary in Plano, Shady Brook Elementary in Bedford, and Oakhurst Elementary, Greenbriar Elementary, North Hi Mount Elementary and E.M. Daggett Middle School in Fort Worth. During the last four years, UNT’s partner schools have found that using art as part of their lessons in English, math, social studies and science has increased the students’ interest and retention, as well as standardized test scores. That’s because the arts speak to children in a language that demonstrates concepts, reveals symbols and forges connections. To understand what is being communicated by art, viewers have to synthesize information and think critically.

Practicing theory Aretha Livingston (’80), Brittany’s fifth-grade teacher at Greenbriar Elementary, says she was skeptical at first. “When we started this, I didn’t know how art could help me teach,” she says. “Now I wouldn’t go back for anything. The art makes a subject tangible, and the kids love to learn about it.” Kelly Smith (’96 M.A.), who teaches language arts and English as a second language to fifth- graders at Oakhurst Elementary, agrees. Last year, when Smith’s students were having a hard time understanding prepositions, she decided to use a painting during the lesson. “When I brought out the painting and asked the students to describe the position of objects relative to each other,” she says, “I immediately got a response.” The students were eagerly shouting sentences out — “The monkey is on her shoulder” — and within minutes they could each identify which word in the sentence was the preposition, Smith says. The discussion didn’t stop there.The students began to discuss the painting itself, interpreting and analyzing the artist’s ideas as revealed in the work and thinking critically. All 46 teachers at Oakhurst use art in the classroom in some way, and every student in the school visits an art museum as part of a lesson every year. Oakhurst Principal Jana Marbut-Ray says adding comprehensive art education to the curriculum has made a tremendous difference in her school. “The teachers are excited about teaching in a way I’ve never seen,” she says. In 1996, Oakhurst began participating in the Challenge. The school’s majority population — Hispanic students who are learning English as a second language — was performing poorly in all subjects on the Texas Assessment of Academic Skills tests. In fact, Oakhurst was ranked a low-performing school by the state of Texas. During the first year of the Challenge, the Hispanic students’ average TAAS writing score was 34.8 percent — below the state’s minimum average. The entire student body’s average score was only 43 percent. In 1997, after one year of using art in the classroom, the writing score for Hispanic students jumped to 60 percent, while the entire student body’s score shot up to 68 percent. In 1998, the scores were 100 percent and 98 percent respectively. The improvements were the result of a total school reform effort. The school implemented a tutoring program and revamped its bilingual education program. But Marbut-Ray says adding art to the curriculum made the most visible, immediate difference.

Community collaboration In order to ensure the schools were able to successfully implement a comprehensive art program, UNT assigned a local museum educator and a mentor from the institute to each school’s site-based management team. Pam Stephens of the UNT institute and Libby Cluett from the Amon Carter Museum were assigned to Oakhurst. During the first year, the team developed writing lessons that centered on narrative paintings at the Amon Carter. In conjunction with the lessons, Cluett says she designed each museum visit to coincide with what the teacher had been doing in class, thus making the museum an extension of the classroom rather than a field trip destination. As a museum educator, Cluett spends most of her days working with teachers and students who visit the museum. She says the partner school students are different. “When they are here, they already know how to read a painting, and they discuss freely, often taking much longer than most students usually do,” she says. “It’s thrilling to see students understanding and using art to its full potential.” Cluett also says working with the partner schools helps her better serve the other students who visit. “Because I’ve been part of a school’s internal meetings and have seen exactly what they are facing, I’m more able to make what I do with all students more relevant,” she says.

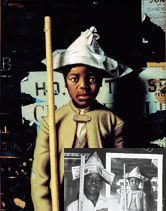

Elevating art Combining the resources of museums with classroom needs is a key part of the Marcus Fellows program. During an intense 12-month period, each class of five fellows spends time learning how to collaborate, use technology and effectively integrate art into school curricula. Amy Lewis (’97 M.A.), education coordinator for the Crow Collection of Asian Art in Dallas, says her training as a Marcus Fellow prepared her perfectly for her job. “The focus of the program is to train people who can effectively make art an accessible and important part of Texas’ communities, so we were trained in ways to do that,” Lewis says. “The purpose of my job is to make the art of Asia approachable and comprehensible to all of the museum’s audiences,” she says. In addition, Lewis and her Marcus Fellow colleagues, who are doing similar work in museums and schools around the state, serve as leaders in the community, teaching others how to integrate art into curriculum. That was the Marcus Foundation’s intent when it funded the program that began in 1995. “We wanted to create a critical mass of highly skilled educators who could serve as a resource to parent groups and other groups concerned with bringing quality education to the schools,” says Melba Whatley, chair of the foundation board. When this academic year ends next August, there will be 30 Marcus Fellows in Texas’ schools and museums, working to weave art back into the fabric of society. Six area principals and hundreds of teachers welcome the support. “We tried

marginalizing the arts, and we even tried to delete them completely,

but the most effective teaching and learning I’ve seen has happened

by integrating the arts,” says Marbut- Ray.

|

|||||||||||||