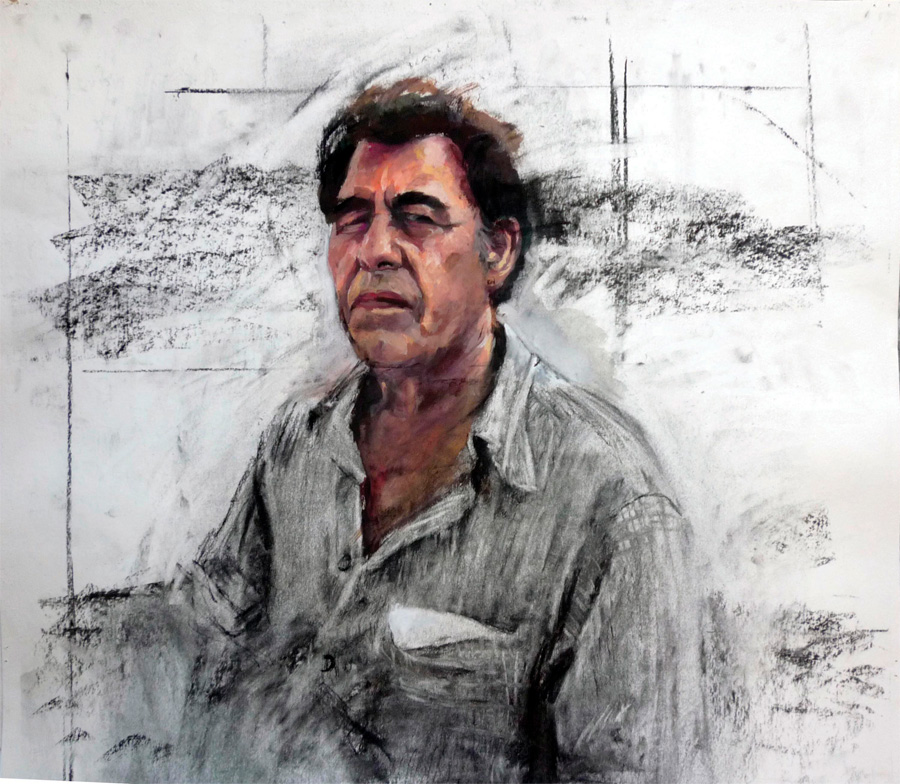

Regularly, he adds color to the portrait but leaves the rest in black and white --

such as in this illustration of day laborer Ricardo.

"One of the things that I like about drawing is that you can often see the hand of

the artist. I render some areas more carefully, while in others, I leave the initial

gestural marks. This gives it more energy. And with color you add another layer of

emphasis."

Approaching potential subjects is not always easy. He is shy, and the subjects can

be reluctant, too. When he visits the camps for immigrants, he asks them if he can

draw their portrait and explains what he's trying to do.

"That opens a lot of conversation. A lot of them are creative. You can start talking

about other things and what they have aspirations for."

His subjects are depicted holding papers or eating or waiting. He'll give them the

drawing. He takes a picture that he will use to create the painting.

Aguirre combines this work while managing the Learning Games Lab at New Mexico State

University in Las Cruces, New Mexico, and teaches at El Paso Community College and

Doña Ana County Community College in Las Cruces, New Mexico.

He would eventually like to see his work exhibited at museums. But he's often satisfied

with the work itself.

"Sometimes you get on a roll," he says. "You kind of lose yourself. You're focused

on painting. It's not necessarily relaxing but it's a good experience."