The Past as a Present

UNT history students, professors and alumni shine a light on disappeared local communities.

Photography by: Michael Clements

June 20, 2020

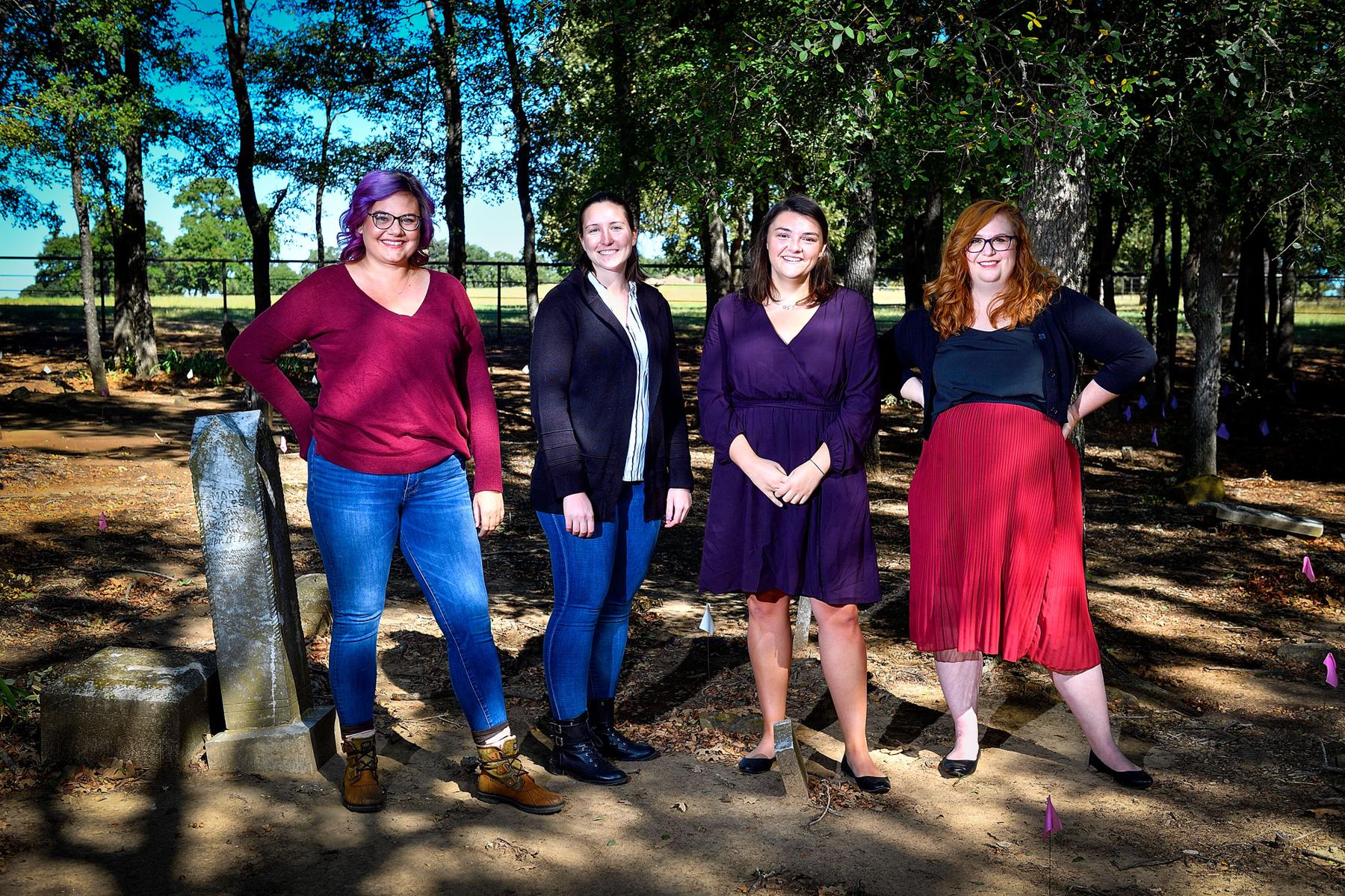

When her name was called, Micah Crittenden (’18, '20 M.A.) walked quickly to the podium,

smoothing her navy blazer and red skirt before opening the three-ring binder she had

meticulously prepared. It was the first time the UNT history graduate student had

spoken in front of the Pilot Point City Council, and this was not, as she well knew,

a low-stakes meeting.

For nearly five years, the council and the Harris family had been at an impasse over a dilapidated house at 522 E. Burks St. — purchased in the late 1940s by now-deceased patriarch Melvin Harris — that the city had ruled substandard in 2014. Pilot Point officials worried the vacant structure was not only an eyesore but a potential danger for neighborhood kids or vagrants. The Harris family needed more time, and more money, to complete the required repairs.

After Emancipation, Louis Whitlow Sr. founded Oakdale on the Cooke County-Denton County

line.

That night, the council was ready to vote on the house’s condemnation. Community members, some of whom were there to rebut concerns over the home, had submitted requests to speak. Crittenden, at the last minute, was one of them. Though not a Pilot Point resident, in the weeks preceding the meeting, she had come to know more about the history of this small town than possibly anyone else in the room.

Case in point, the binder. Inside were property and census and draft records that sketched a brief history of Harris and, crucially, evidence that his home had previously been a one-room schoolhouse for African American students — locally, the last of its kind — in a lost community known as Oakdale.

“If you’ll give me a moment, I’d like to tell you the story I’ve uncovered.”

Crittenden flipped a few pages, cleared her throat. The tale begins, she told them, after Emancipation, when a sharecropper named Louis Whitlow Sr. from Chambers County, Alabama, took 65 freed men, women and children and founded a community on the Cooke County-Denton County line. In 1905, the community built, as part of its St. James Baptist Church, a one-room structure that housed a school.

“That structure,” she said, “is located at 522 E. Burks St.”

That seemed to get the council’s attention, but after more than an hour of terse arguing between city officials and the Harris family, they were still on the fence. Whether out of genuine interest or simple exhaustion, the members struck a deal: Find more evidence that the house is what you say it is, they told Crittenden, along with some possible sources for funding, and we’ll leave the home standing.

And that’s how, in the two months and more than 200 hours of research that followed, she came to play a starring role in rescuing one of the last remaining relics of a disappeared community.

Tracing how Crittenden arrived at that juncture is not unlike her journey through the documents and photos and stories that coalesced to reveal, in wide brush strokes, the portrait of a vanished neighborhood. It’s a circuitous path, in which one stepping stone leads to another and back again.

And it all begins with two UNT professors who trusted their students enough to collect, explore and connect with local history.

No stone unturned

It was the first day of class, but Todd Moye and Andrew Torget had far more planned for their students than the traditional rundown of required reading, test dates and attendance policies. The two, buoyed by anticipation and high expectations, jumped right into the heart of their public history research seminar, sharing the genesis of what would become a semester-long — and for a few of the students, longer — quest to uncover the story of the St. John’s community.

“Not only do we not know what the end result will look like,” Moye told the assemblage of undergraduate and graduate students, their faces a cocktail of apprehension, curiosity and excitement. “But we don’t know if it’s even possible to come up with one.”

He and Torget never intended to turn the class into a mystery, but at the end of the day, they figured, isn’t most research detective work? Might as well confront the intimidation factor head on and turn their students into the kind of dogged historical investigators who would leave no stone unturned — which, in this course, would often literally be the case.

In recent years, the Denton County Office of History and Culture had assumed responsibility for the upkeep of St. John’s Cemetery, the overgrown burial grounds for African Americans who had called the freedmen’s community near Pilot Point home, and conducted research into the site with limited resources. Intrigued by what little they knew about St. John’s, Moye and Torget offered to develop a class that would center on discovering more about the families buried there. But considering former residents of St. John’s had long ago scattered to the winds, finding any trace of detailed records or living descendants would be tough, if not downright impossible.

“We took a leap of faith that we could figure out who the people were and what their lives were like along the way,” Moye says. “‘Let’s try to figure this out together’ is a really exciting thing to be able to say to students.”

Prior to the start of the spring 2018 semester, Moye and Torget spent a year laying the groundwork for the course, with their previous experience guiding the preparation. In 2016, they led a seminar in which students investigated the 1956 integration of Mansfield High School, a project that resulted in the creation of an online museum, as well as deep connections among the students and the city’s African American community. The findings were incorporated into Mansfield’s 50th anniversary celebration of the school’s integration, and local community colleges use the research to teach about civil rights.

For the St. John’s project, Moye and Torget split the class into six teams and tasked them with delving into everything from the history of St. John’s Baptist Church and St. John’s Cemetery to the community’s social, geographic and economic connections. The students then uploaded their findings to an Omeka database created and hosted by the UNT Libraries.

“It becomes an intoxicating thing,” says Torget, who last year set the Guinness World Record for longest history lesson following a non-stop 26-hour lecture on Texas history. “It’s up to the students to make the discoveries and the decisions. They take ownership and responsibility for the information in a way they aren’t typically asked to.”

Sparking curiosity

What also was intriguing, and deeply unsettling, was the stark reality of disappeared communities in the North Texas region. During the first few weeks of class, the professors had their students read a thesis penned by former UNT history student Chelsea Stallings (’09, ’15 M.A.). Her work detailed the dissolution of Quakertown, a robust local freedmen’s community that in 1921 was displaced by Denton officials under the guise of “beautifying the city with a public park.”

The entrance to St. John's Cemetery in Pilot Point, which is surrounded by private

property.

That year, a majority of the city’s white citizens voted to remove Quakertown residents from their home, a middle-class neighborhood that included medical facilities, stores, churches and a school, and built Civic Center Park — renamed “Quakertown Park” in 2007 — in its stead. After many of their homes and businesses were seized, or purchased for pennies on the dollar, Quakertown families were relocated to a barren cow pasture.

“It blew my mind that there was so much we don’t talk about and hasn’t been known because we traditionally have a white-dominated history,” says Stallings, who notes that when she was a history student, Moye “pushed me in ways I didn’t even realize at the time.” She’s currently pursuing a Ph.D. in history at TCU and is one of the leaders of the Denton County Community Remembrance Project, an extension of Alabama’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice, that seeks to memorialize lynching victims. “We’ve had African American communities who have done so many amazing things in the area, and we, as white people, have historically torn them down.”

There are several carved gravestones in St. John's Cemetery, while other graves are

marked with rocks. Pilot Point native John White visited Moye and Torget's class to

relay the stories his grandmother told him about St. John's, including ones about

his ancestors who are buried there. One such relative is J.D. White, whose gravestone

is seen at bottom left.

Stallings’ research lit a fire in Crittenden and her classmates to reconstruct the St. John’s narrative, which was in many ways different from that of Quakertown. Settled during Reconstruction by black Alabamians, St. John’s began to dwindle in the 1920s when residents left for better economic prospects and, as would become apparent to the students later, to flee racial violence. But the history of the community and its people had likewise been allowed to fade into obscurity. The frequently careless storage of documents related to African American citizens, coupled with the fact that few residents kept diaries or wrote letters, meant many freedmen’s communities had practically vanished from the historical record, and the artifacts that did survive were often housed in dusty, forgotten boxes, uncataloged and uncared for.

Crittenden was assigned to the “People of St. John’s” team, a group that included undergrads Emily Bowles (’18) and Jessica Floyd (’18) and grad student Hannah Stewart ('17, '19 M.A.). The team scoured historical databases like the Portal to Texas History, and reached out to the Denton County Office of History and Culture, who led them to John White. He visited the class to recount his memories of his grandmother, who moved from Camp Hill, Alabama, to St. John’s in 1883 when she was 5 years old, and brought photos of his ancestors who are buried in the cemetery. White grew up on the outskirts of Pilot Point, raised in the shadow of St. John’s forgotten history, and as he spoke to Moye and Torget’s students, he relayed the stories his grandmother had passed on to him about the community, as well as his desire to see some light finally shed on its legacy.

Littel (Little) Safe Smith and the infant's parents are buried in St. John's Cemetery.

“I want other people to know the history of St. John’s — I don’t want it to end with me,” says White, who from 2016 to 2018 served on the Pilot Point City Council. “I’m not going to be here very long at my age, and I have kids and grandkids and relatives who don’t know their history. If you don’t know where you came from, there’s a chance you don’t know where you’re going. So I want this history to be available to everyone.”

The team’s task in uncovering that history sometimes required getting down and dirty — they often found themselves on their hands and knees, flipping over headstones hidden under overgrown foliage. Among a row of infant plots, they uncovered a grave marked “Littel (Little) Safe Smith,” with the name and dates meticulously hand-carved into the stone. In the weeks before that discovery, they had cobbled together bios of the parents, Henry and Lissie, and knew the couple had lost a child. What they didn’t know was how galvanizing unearthing the tombstone would be.

“I was just so heartbroken, I started bawling right there by the grave,” says Bowles, a single mother who continued to visit the cemetery even after her research was concluded. “That’s when I knew how much I genuinely cared about this community.”

The group found more information about the people of St. John’s than they ever thought possible. They contributed 49 individual biographies to the Omeka database, which now contains more than 650 artifacts related to St. John’s, including photos, official records, oral histories and news clippings.

Willie Hudspeth (’90, ’93 M.Ed.), president of the Denton County NAACP and a longtime

local civil rights advocate who was one of the first to press for the preservation

of St. John’s Cemetery, is pictured in front of the Denton County Courthouse. Hudspeth

visited Moye and Torget's class on the final day of the semester to see what their

students had uncovered about the St. John's community.

When White visited earlier in the semester, he promised he would return on the final day of class to see the students’ work. He kept his word, reappearing alongside Peggy Riddle, director of the Denton County Office of History and Culture, and Willie Hudspeth (’90, ’93 M.Ed.), president of the Denton County NAACP and a longtime local civil rights advocate who was one of the first to press for the preservation of St. John’s Cemetery. He has painstakingly pulled weeds and removed debris by hand to ensure that the grave markers in the cemetery — many of which are simple rocks — remain undisturbed.

As the students’ presentation unfolded, other long-ago images flickered through Hudspeth’s mind. He traveled back to 1963, to when he was a 15-year-old growing up in segregated north Fort Worth and saw a classmate return to school battered and bruised in the wake of a brutal, racially motivated attack. It wasn’t the first, or final, time he would bear witness to that level of violence.

“When they started talking about St. John’s and Pilot Point and what they had found out, it took me back to when I first started to understand what was happening to me and my community as black people. There’s nowhere to go to get help, you’re just out there by yourself. And I was angry — I was so angry back then,” Hudspeth says. “But boy, those students worked hard. What they came up with lets us understand what happened and helps us move forward.”

That’s what the students most wanted — not a grade or a portfolio piece, but to see that, at the end of the day, their research mattered.

“It’s true that you always hope your students will empathize with the people they’re researching,” Moye says, “but you can’t always be sure they will. These students absolutely felt like they had to do right by St. John’s.”

The quest continues

As the spring semester drew to a close, Crittenden, Bowles, Floyd and Stewart weren’t ready to call it quits. They had spent months thinking about St. John’s — combing through birth and death certificates, marriage and war discharge records — but they still weren’t certain why the community so quickly disbanded in the early 20th century.

“Sometimes you can fill in those gaps, and sometimes the records aren’t there,” says Torget, who became the students’ advisor for an independent study project on St. John’s, along with Moye. “But that compulsion to finish the story, answer the question, resurrect a community — that becomes bigger than the assignment itself.”

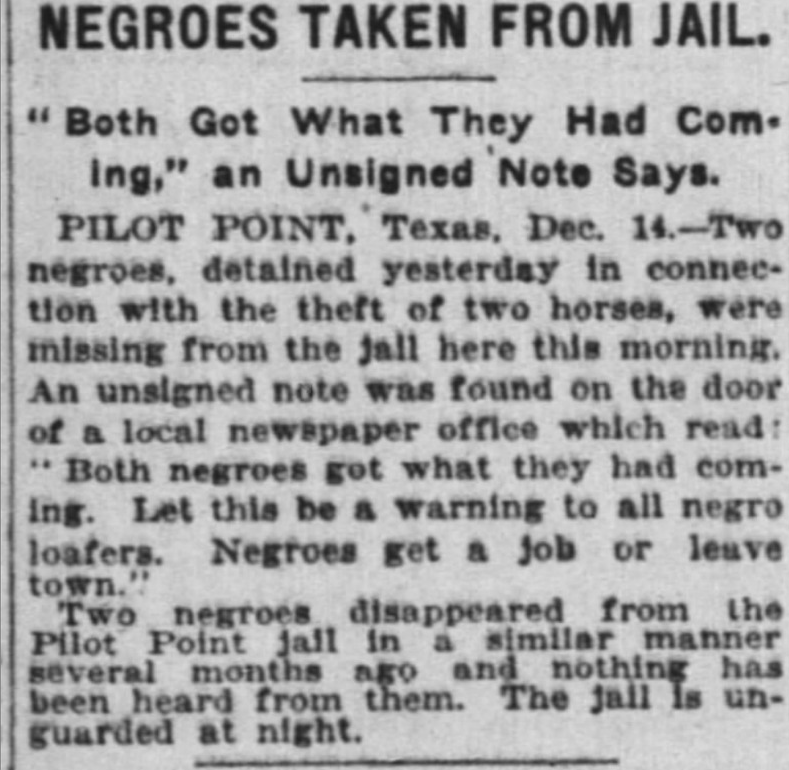

A news bulletin from 1922 detailed the disappearance of two alleged horse thieves

from the Pilot Point jail.

So when he stumbled across a Denton Record-Chronicle article about a lynching that took place in December 1922, Torget knew it was something the team needed to see. A news bulletin from the time detailed that two men, detained at the Pilot Point jail for horse theft, were reported missing the next day. An unsigned note was found on the door of the local newspaper office. “Both negroes got what they had coming,” it said. “Let this be a warning to all negro loafers. Negroes get a job or leave town.”

The bulletin concluded just as chillingly, noting that two men who had similarly disappeared from lockup several months before were never heard from again. The jail, the reporter disclosed in the final line, is unguarded at night.

“It made me feel ignorant, realizing that this area had a much darker history than I ever thought,” Floyd says. “I knew the South had been adamant in keeping Jim Crow laws, I knew about the issues with Mansfield’s integration. But it didn’t really hit home until I saw the evidence that Denton County played a massive part in this kind of racial violence, well into the 20th century.”

The team spent months scrutinizing local news reports from the early 1900s, many of which made mention of vanished African American residents and Ku Klux Klan activity. There were articles that even praised those complicit in such activities, some of whom were Denton County officials, as “upstanding citizens.”

It was heartbreaking to see that they came here hoping for a better life. For many,

that did happen. But for others, it was taken away from them.

Hannah Stewart ('17, '19 M.A.)

This unchecked impunity, the students realized, is why so many St. John’s residents had abandoned the community they called home. And they had the facts to prove it. Stewart created a spreadsheet that contained every mention of the KKK in local newspapers and records from 1917 to 1928. Crittenden compiled one that detailed reports of every African American arrested locally from 1909 to 1925. The data was conclusive: Klan activity surged around the same time crimes allegedly committed by black residents occurred. And with jails conveniently left unguarded, Jim Crow justice reigned.

“It was hard to see that this kind of thing is what they were facing every day,” Stewart says. “You’ve gotten to know these people, you’re rooting for them on census records as you’re tracking their lives. They’re players in history, but it’s so personal at this point. It was heartbreaking to see that they came here hoping for a better life. For many, that did happen. But for others, it was taken away from them.”

It seemed like the sun had been allowed to set on Denton County’s unseemly past. But then, the truth was at long last thrust into the spotlight: Media outlets began to pick up the story of the students and their research. Articles were penned in the Denton Record-Chronicle and The Dallas Morning News, segments were filmed for NBC 5. Torget recounts running into several Dentonites who mentioned the students’ work and marveled at what they had uncovered.

The four student researchers then presented their findings of what life was like for the residents of St. John’s to the Denton County Commissioners Court, who drew upon their account when applying for a funding application for an Untold Story marker from the Texas Historical Commission. Riddle said the Office of History and Culture soon hopes to employ infrared technology to better locate gravesites at St. John’s Cemetery and plans to set up family visitation days where residents can see the site. The cemetery is surrounded on all sides by private property, meaning permission is required to visit.

The students and Hudspeth say such plans are a step in the right direction, but there’s still plenty of road to travel. It’s vital, they say, that the people who lived and died and fled and vanished from St. John’s can finally, and properly, be remembered.

“This is a history people don’t want to be reminded of,” Hudspeth says. “It brings to mind what happened to so many people and what’s happening to people now. Let’s bring up this history and examine it, so we can teach our children and everyone else to never let this happen again.”

Delving deeper

Before the conclusion of the fall 2018 semester, the group placed a bouquet of metal flowers near the entrance to the cemetery. It was a tribute, and in some ways, a goodbye. They hadn’t found the answers to all their questions, an impossible task in just one year. Still, they understood it was time to move on.

Stewart earned her master’s in education in spring 2019, and began work as a middle school history teacher. Floyd graduated in fall 2018 and began to pursue a teaching certification. Bowles had applied and was accepted to UNT’s history master’s program.

Crittenden, too, had begun embarking on her master’s that fall, but she couldn’t shake the startling nature of her findings, and those of Stallings previously. If there was more out there to discover, and she knew there must be, maybe she was just the person for the job.

She thought of how Torget signed his emails when she informed him of a new discovery: “Onward.”

So disappearances became the subject of her thesis — specifically, those that occurred in Denton County during the Jim Crow era following interactions with the justice system. When she told Moye, he asked, “Are you sure you don’t just want to write a really pretty biography?”

They both knew the answer to that question.

In an oral history she provided as part of the St. John's research project, Pearlie

Mae Simpson told the story of her mother’s baptism in Oakdale, in a creek that ran

behind the St. James Baptist Church and an adjacent schoolhouse.

Crittenden started compiling records from Ancestry.com and the UNT Libraries’ vast collection of online databases. The hours upon hours of information gathering had a weirdly calming effect on her brain — “like playing Sudoku,” she says. But as she fell further down the rabbit hole of Denton County history, there was more urgency to claw her way to the truth.

One key was to figure out what had happened to the two men mentioned at the end of the 1922 news bulletin, who had disappeared from the Pilot Point jail several months prior to the disappearance of the alleged horse thieves who were the subject of the article. Shortly before the men vanished in October 1921, they were taken to a property just north of town and flogged. The property was owned by a man named Joe Burks, whose father, William D. Burks Sr., was formerly a mayor of Pilot Point. As Crittenden tried to locate more information about Joe, she kept stumbling over present-day stories of a house on Burks Street that the Pilot Point City Council was considering condemning. The surnames of those speaking to save the home — Harris, Holloway — seemed oddly familiar. And then it hit her: The names were connected to St. John’s.

Though it was only a few weeks before the rough draft of her first thesis chapter was due, Crittenden reached out to the Office of History and Culture to help connect her with the Harris family. Family members told her they believed the home had once been a one-room schoolhouse in Oakdale, known as the Lincoln Academy, that had been transplanted to Burks Street sometime in the 1940s after Melvin Harris purchased it. An oral history Crittenden and her teammates gathered during the St. John’s project lent credence to the claim that the Oakdale structure had existed. One descendant, Pearlie Mae Simpson, told the story of her mother’s baptism in Oakdale, in a creek that ran behind the St. James Baptist Church and an adjacent schoolhouse.

Crittenden looked for all the records she could in the two weeks leading up to the city council meeting, securing copies of any evidence she found in her binder. As a community, Oakdale was long gone — the area existed where Lake Ray Roberts now resides. But the Harris family had placed their hopes in her research expertise, and she was determined to not let them down.

A race to preserve history

The meeting wasn’t exactly a resounding success — the council’s concession to leave the home standing, at least for a while longer, didn’t read as a slam dunk. But for the Harris family, who just a few weeks ago were almost certain the Burks Street house would face demolition, Crittenden had helped secure a much-needed victory.

“It feels like everything in our community is being dissolved,” Melvin’s granddaughter Cecelia Harris told Crittenden as the meeting concluded. During the proceedings, Cecelia grew increasingly upset as councilmembers again and again cited the potential dangers the home posed to trespassers. Why, she asked, is it more important to protect those violating the property than it is to protect the property itself?

Still, Cecelia exited the room with some small measure of relief. “Before, we didn’t have anybody to take on this issue with us. Now, with us joining together, maybe it will all work out.” Before she departed city hall, guided into the night by a glimmer of hope, Crittenden handed her the binder. “I want you to have this,” she said. As Cecelia softly wept, the two embraced.

“I’ll see you soon,” Crittenden promised.

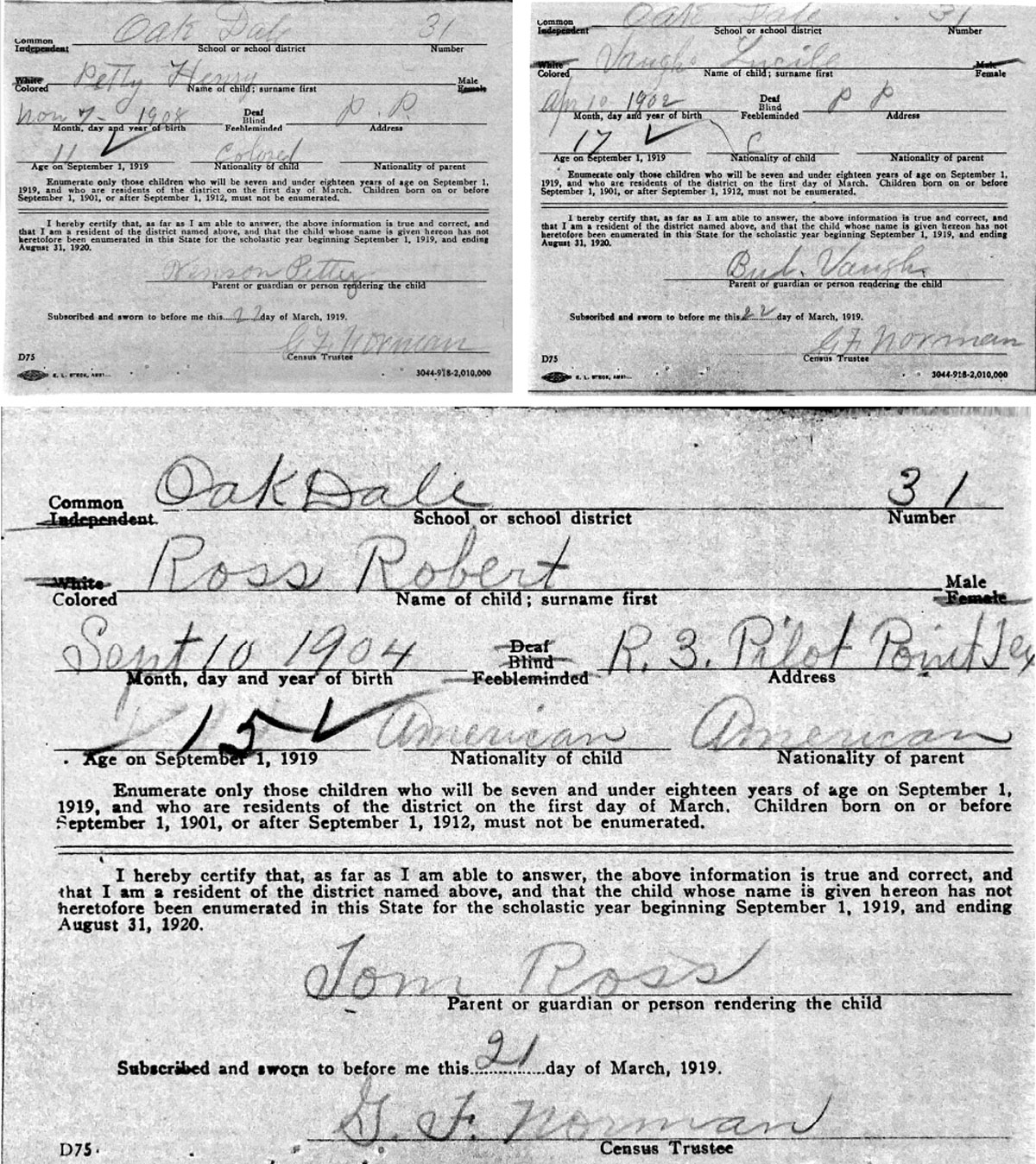

In her quest to save the Burks Street residence, Crittenden found records of students

who attended the Oakdale school.

“Soon” was the operative word. The council had given her roughly 60 days to find definitive proof that the house was in fact the Oakdale school, and to find potential sources to fund renovations. With three kids at home, a job as a teaching assistant, and her own thesis to continue writing, it wasn’t going to be easy.

But preserving a last-of-its-kind piece of local history was, she knew, worth the effort.

So she did exactly what she had been taught to do — scoured databases, visited county records offices, talked to people who were from the community or knew people who were. When clerks would tell her no such records existed, she’d insist on looking anyway. She discovered papers containing information about Lincoln Academy students that had been stapled together and stored in Cooke County, in an old card catalog labeled “colored school records.”

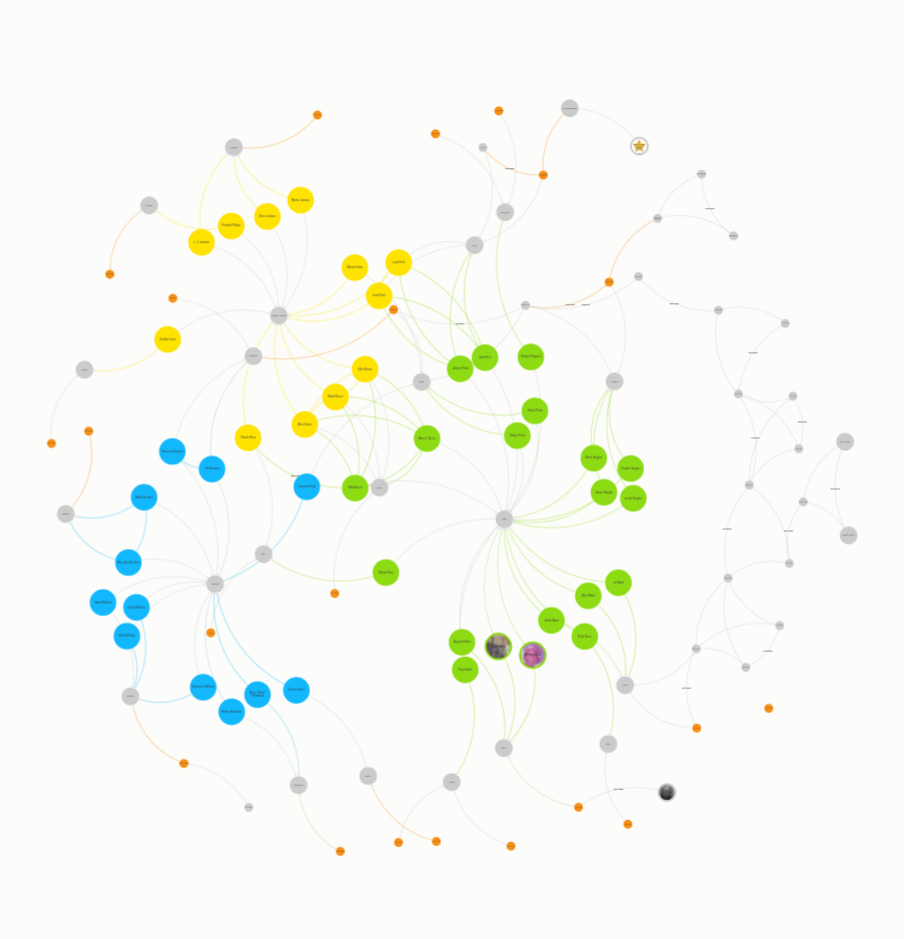

After more than 200 hours of research, she had pieced together a portrait of the academy and its attendees. With school and census records, she created social maps to show how communities like Oakdale, St. John’s and others were inextricably linked. She found land records proving that when Oakdale consolidated with Pilot Point in the 1940s, the structure that housed the school was moved five miles south to its current location on Burks Street. And she identified grants that could potentially offset the cost of repairs.

Crittenden created social maps to show how communities like Oakdale, St. John’s and

others were inextricably linked.

On June 24, two months after her first presentation, Crittenden again appeared in front of the Pilot Point City Council. She wasn’t quite so apprehensive this time, in part because she sensed the tenor of the room had shifted. After giving a 30-minute presentation on what she had discovered, she fielded questions that led to a freeform discussion with the council, community members and Rosalene Sledge, the current owner of the home. When Crittenden explained that the grants she had found would likely take a long time to complete and were uncertain to fully cover the cost of renovations, Riddle pledged the Office of History and Culture’s monetary support, offering to relocate the house to the Denton County Historical Park and pay for its upkeep. Community members threw out the names of contractors who could potentially help with repairs, and other residents proposed starting a GoFundMe page.

“There was an interplay between people that made me feel like the home would be safe,” Crittenden says.

The indisputable happy ending would be for the Harris family to keep the building that Melvin rescued and transformed into a home. But still, Crittenden was right — even if they can’t raise the money for the required repairs, one way or another, the structure will be saved from demolition.

More than 100 years after it first opened its doors to educate Oakdale’s African American community, Lincoln Academy had itself become a lesson in Denton County history.

‘The only way I know how’

For now, Crittenden’s research into the Burks Street residence is done. In June, she applied for funding for an Untold Story historical marker to honor the Oakdale community. If granted, she will ask that the eventual marker — with the blessing of the Harris family — be placed in front of the home.

She’s also lending her expertise to the Denton County Community Remembrance Project. Recently, she proposed five possible locations in which to collect a soil sample meant to represent the bodies and burial of lynching victims. The Pilot Point jail and St. John’s Cemetery were two of the sites on her list.

And finally, she’s compiling nearly two years of research into her thesis, which includes digital components like social graphs built on Kumu, and chapters dedicated to the victims of violence in Denton County.

It’s not a definitive history, she knows, but it’s a start. And when you sense that something isn’t right — that the past has been forgotten or overlooked or marginalized — there’s no time like the present to do something about it.

“You just have to trust that you can do it,” says Crittenden, who will begin UNT's Ph.D. history program this fall. It’s after dark, and she’s sitting on an old wooden picnic bench outside of Pilot Point City Hall, taking a moment to gather her things before heading home to her husband and kids. “Whatever amount of privilege I’ve been handed, I’m going to use it to hold the door open. That’s the best way I can be a human.”

She stops for a moment and gazes at the building where, just minutes before, history had triumphed.

“It’s the only way I know how.”