Travel with Care

As the volunteer tourism industry continues to expand, UNT students and alums find

ways to help communities at home and abroad.

June 17, 2019

Scuba diving was nothing new for Ryan Cox ('97). Whenever the computer science alum accrued a little vacation time from his

IT role at IBM, he happily headed for open waters, mask and tank in tow.

"I was scuba diving every day, and what was even better is that it was for a good

cause."-- Ryan Cox ('97)

Measuring the lip thickness of queen conch -- now that was a different story.

Because at the southern tip of Belize, in the Port Honduras Marine Reserve, Cox was taking both a literal and figurative plunge: using his diving skills not just for recreation, but to aid in essential research. Through the Earthwatch Institute -- which funds programs that unite researchers, conservation volunteers, non-governmental organizations and businesses to build a more sustainable environment -- Cox was helping local scientists determine how the overharvesting of queen conch was affecting the marine ecosystem.

That meant he was responsible for some of the project's "grunt work." He dove three times a day to lay transects, and on an underwater tablet, he counted the conch within each one. He also measured the conch's lips to identify their age, which determines their potential for repopulation.

"I was scuba diving every day, and what was even better is that it was for a good cause," says Cox, who has taken part in two other trips: one in 2002 that focused on coral bleaching near San Salvador Island, and one in 2009 that centered on climate change in Borneo's rainforest. "It's a win-win for everyone -- the scientists can focus on the overarching goals of their project, and the volunteers learn a ton about the research. It's eye opening."

A growing industry

Cox's experience falls under the umbrella of what is referred to as "volunteer" or "service-based" tourism, a booming industry that sees an estimated 1.6 million tourists spending as much as $2 billion annually. The trend began as a way for NGOs to support long-term international volunteers with short-term support in projects ranging from conservation and construction to education and health services. And while there have been plenty of positive outcomes since -- including, as in Cox's case, volunteers performing rote tasks that enable experts to focus on their mission's bigger picture -- debate often swirls as to whether travelers' good intentions can unintentionally lead to bad results. These include disruption of local economies and cultures and hindering of the work.

"As I've gotten older, I've realized I want to do projects where it's more about getting

a job done, something that will last and help the community for a long time." -- Chris

Welhausen ('19)

"I genuinely feel most of these communities are thankful for help with infrastructure development and the establishment of projects that enable them to be self-sufficient," says Birendra KC, an assistant professor in UNT's Department of Hospitality and Tourism Management whose research interests include nature-based and community-based tourism. "But that only happens if there is a proper way of doing things -- most importantly, a very specific schedule of the tasks that need to be completed along with a clear vision of how volunteers can truly help the community."

Over the years, many UNT students and alums have ventured out on service-based trips, which break down into categories such as ecotourism and community and urban outreach. Those experiences have been invaluable, they say, particularly in thinking about how to be responsible travelers and better evaluate the efficacy of volunteer organizations.

"I learned how important it is to look for the most productive ways to contribute to the community," says Chris Welhausen ('16), an advertising alum who volunteered in Nepal in 2013 and now works as a traffic manager at Sherry Matthews Advocacy Marketing in Austin, which focuses solely on campaigns for social good. "If you have particular skills, it makes sense to use them to give back."

Gaining perspective

"You get to know the kids -- that made it hard to leave -- but at least you leave

knowing they'll have a chance at an education. It was the best vacation I've ever

been on." -- Joy Tipping ('90)

It was a 90-minute bus trek to the mountain village near St. Martín Jilotepeque, Guatemala, where Joy Tipping ('90) and her fellow WorldVentures Foundation volunteers were tasked with helping to build a bottle school for local children in 2016. All the way up, Tipping was struck by the beauty of the countryside, and by the trash that littered it -- piles of soda bottles and chip bags and candy wrappers.

"There's nowhere to put it, and they can't burn it," she says.

In conjunction with Hug It Forward -- an international, U.S.-based grassroots organization that raises awareness of improved trash management methods through the construction of bottle classrooms -- the WorldVentures volunteers completed construction projects throughout the week. Tipping cut rebar to help construct the school and, on the weekends, was visited by village children who were eager to help. The villagers pre-stuffed 20-ounce plastic drink bottles with non-biodegradable trash until they were dense enough to serve as bricks for the school.

"For them to have a school in that village was a miracle," says Tipping, a broadcast journalism alum. "You get to know the kids -- that made it hard to leave -- but at least you leave knowing they'll have a chance at an education. It was the best vacation I've ever been on, and everyone was just so welcoming."

Jamie Johnson ('01), a lecturer in UNT's Department of Anthropology, says the reaction of local communities to volunteer travelers is key to understanding whether the organizations those volunteers are affiliated with are helping or hurting. While that can be impossible to gauge until you arrive, there are other ways to do your homework.

"It's imperative for the traveler to understand who these organizations are, how long they've been there, when they were founded and by whom, and if they were invited into the community or just suddenly appeared," Johnson says. "It's important to remember that any kind of tourism is irreparably tied to the global market, and at some level, these communities are going to feel commodified. But ethnographer João Afonso Baptista posed the question: 'Can tourists be the solution rather than the problem?' I think if you're a traveler and keep that question in mind, then the answer can be yes."

I'm a big believer in serving your community first -- there are a ton of problems

at your back door, so you don't have to travel far to help, but if you're already

doing that, why not combine travel with giving back?

Chris Welhausen

For Welhausen, whose volunteer trip to Nepal involved working as a caretaker at an orphanage for children of Tibetan refugees, the vacation tapped into his already well-honed love of community outreach. As a member of the service group Alpha Phi Omega at UNT, he was volunteering with numerous organizations, including Keep Denton Beautiful.

"I'm a big believer in serving your community first -- there are a ton of problems at your back door, so you don't have to travel far to help," he says. "But if you're already doing that, why not combine travel with giving back?"

So in 2013, Welhausen signed up with International Volunteer HQ, which offers service opportunities in more than 40 countries. He was stationed in Pokhara, a town by the Himalayas, where he was "constantly blown away," he says. He spent three weeks at the orphanage, helping with homework, preparing meals and walking the children to school. They laughed together, played soccer and swam.

And though it was an unforgettable experience, he says he couldn't shake the feeling that maybe he could have contributed in a more permanent way.

"As I've gotten older, I've realized I want to do projects where it's more about getting a job done, something that will last and help the community for a long time," he says. "I want my next trip to be a construction-related project, like building schools in South America."

A deeper understanding

"Those experiences are going to stick with me the rest of my career. I'm much more

aware now. Human trafficking is such a hidden topic, but it's important for everyone

to realize it happens in the U.S., too." -- Allyson Neisig ('19)

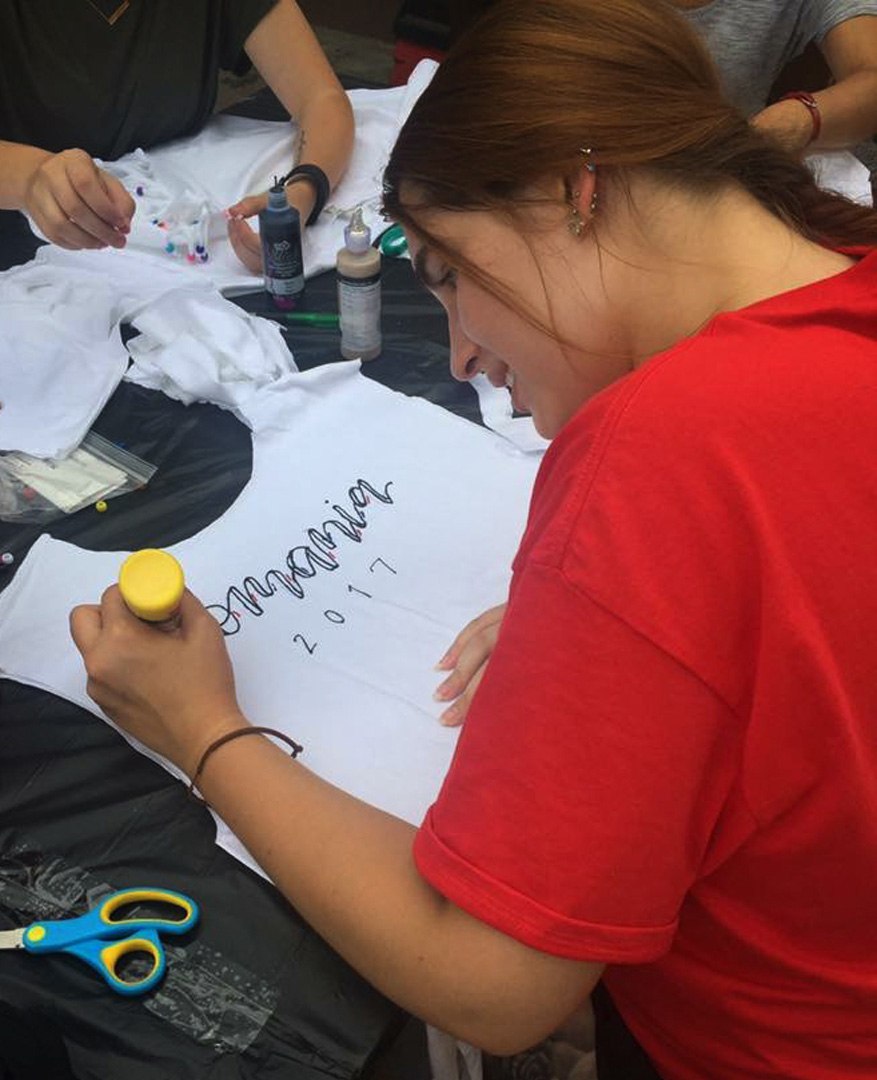

In August, Allyson Neisig ('19) will begin her studies at the New England School of Law. It's not the path the criminal justice graduate pictured for herself when she entered UNT in 2015, but that was before -- before she signed up for a study abroad trip to Romania in 2017, before she returned to the region on her own a year later, before she realized the prevalence of human trafficking not only internationally but right here in the U.S.

"Those experiences are going to stick with me the rest of my career," says Neisig, who on her study abroad trip worked with Open Door, a foundation that provides full assistance and emergency shelter to victims of human trafficking. "I'm much more aware now. Human trafficking is such a hidden topic, but it's important for everyone to realize it happens in the U.S., too. "

In June 2018, Neisig returned on her own to work with Open Door, following a two-week stop in Thailand through We are Bamboo, where she helped build roads in local villages and the foundation for an elephant hospital. In Romania, her trip involved working at Open Door's shelter, where she assisted with rehabilitation activities, observing and asking questions along the way.

When she returned to UNT in the fall, she detailed her findings at an international human trafficking conference hosted by the University of Toledo. There she talked with law professors and realized that, as a lawyer, she could advocate in various capacities for victims of domestic violence and human trafficking. But that determination started, she says, with the decision to use her study abroad stipend to learn -- and help.

"What's the point of traveling," Neisig says, "if you can't serve?"

Ryan Cox ('97) measures the lip thickness of a queen conch at the Port Honduras Marine

Reserve in Belize.

Belize was rife with plants and wildlife, and scientists from Earthwatch worked to

ensure the sustainability of the region with help from volunteers like Cox.

Cox trekked through the Borneo rainforest as part of a 2009 Earthwatch trip that centered

on the effects of climate change there. The research, Cox says, is "eye opening."

Joy Tipping ('90) hugs a child from a mountain village near St. Martín Jilotepeque,

Guatemala, where Tipping and other WorldVentures Foundation volunteers helped build

a bottle school.

The WorldVentures Foundation volunteers dance with schoolchildren who ultimately attended

the school they helped build. "For them to have a school in that village was a miracle,"

Tipping says.

Allyson Neisig ('19) works with children as part of Open Door, a Romania-based foundation

that provides full assistance and emergency shelter to victims of human trafficking.

Neisig creates a shirt during her study abroad trip to Romania in 2017. The trip,

she says, was life-changing. Those experiences are going to stick with me the rest

of my career.

Chris Welhausen ('16), second from right, volunteered at a food bank in Memphis in

2014 as part of UNT's Alternative Service Breaks program. He also volunteered at an

orphanage in Nepal in 2013.

Students hold up the UNT battle flag as part of a study abroad trip to Nicaragua sponsored

by UNT and Explore Study Abroad, an Austin-based business owned by alumnus Anthony

Spence ('03 M.S.).

UNT junior Cierra Black, above center, served as an ASB site leader at Camp Fire in

Oklahoma during spring break 2019.

Participants in the Camp Fire ASB sit in a reflection circle, in which they discussed

their experiences each day.

"Today’s college students want to help the world more than any group I've ever seen,

and universities are pushing service-learning projects because they want to reinforce

that desire to give back." -- Anthony Spencer ('03 M.J.)

That mentality is no stranger to Anthony Spencer ('03 M.J.), a journalism alum who owns Austin-based Explore Study Abroad. ESA develops faculty-led programs in conjunction with local universities, NGOs and other education institutions throughout Nicaragua, Costa Rica and Panama and currently works with numerous American universities, including UNT.

As an undergraduate and graduate student, Spencer participated in several study abroad trips. They stoked his love of service-based travel and provided him with the knowledge to enter the industry as an entrepreneur.

"Today's college students want to help the world more than any group I've ever seen, and universities are pushing service-learning projects because they want to reinforce that desire to give back," Spencer says. "But you have to do it very carefully. You have to take the true skills of the students into account, and remind them that it's not just about working in the community -- it's about working with the community."

In that vein, ESA offers students research opportunities such as living with indigenous cultures in Nicaragua's Miskito Coast, while simultaneously teaching the importance of gifting time instead of possessions.

"One time in Costa Rica we did a Christmas gift activity, and in retrospect, that was a bad moment. It cements this idea that Americans represent material things," Spencer says. "But if students are working with kids or painting the wall of a school, that's a different picture. It's about reaching a better understanding of the global community and how to truly be part of it."

That was certainly the case for Cox, whose ecotourism experiences brought him a deeper, undeniable understanding of the devastating environmental catastrophes international areas were experiencing.

"After dinner, the professors would give short lectures to teach us about what they had uncovered in their research projects," he says. "Being around people who had been studying these topics for a long time made it really clear how true and important these issues are."

In their own backyard

"I can't explain how much it means to me to be able to do this. I want to be an advocate.

This is what I'm meant to do." -- Cierra Black, junior

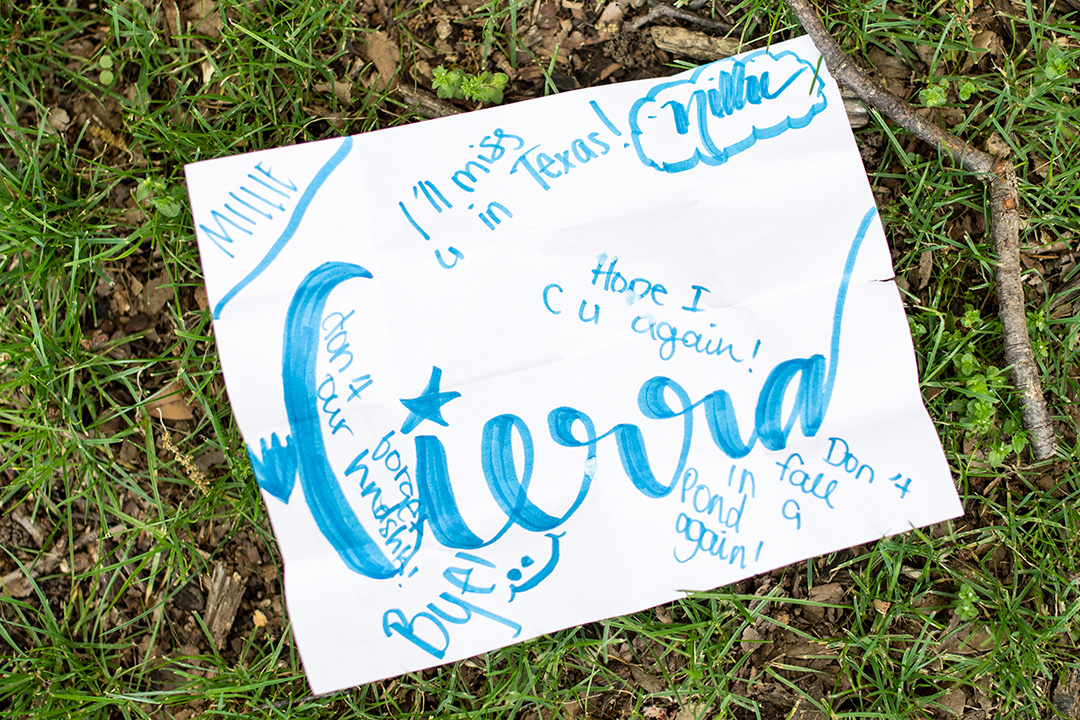

Over spring break, at Camp Fire in Oklahoma, Cierra Black and other UNT students were tasked with helping middle schoolers find their spark. The theme for the week was "Superheroes," and Black paired off with Millie, a sixth grader who transformed into "Purple Girl" -- a math genius whose primary superpower was invisibility.

"She told me she wanted to be a doctor," says Black, a junior public health major. "And I said, 'Maybe I can be your physician assistant one day.'"

The trip to Camp Fire was part of UNT's biannual Alternative Service Breaks program, in which students travel to communities throughout the U.S. to learn about social issues and injustices through intensive service-learning experiences. For Millie, the week further kindled her passion for medicine, while Black and others saw their dedication to service undeniably ignited.

"I can't explain how much it means to me to be able to do this," says Black, who served as the ASB site leader. "I want to be an advocate. This is what I'm meant to do."

Black also combines international travel and service. She spent last summer in Honduras as part of UNT's chapter of Global Medical Brigades, and this summer is helping children with developmental disabilities in Australia and New Zealand. But she has realized the importance of urban outreach, too. She previously participated in an ASB to Our House in Little Rock, which assists the homeless, and has worked with her church to help Dallas' homeless population.

"By 2020, almost 60 percent of the world will live in urban areas, which means structural violence, systemic inequality and a lack of resources," Johnson says. "If Americans want to volunteer, there are plenty of places in our own backyard that are in dire need."

And alums have heeded that call. Upon his return from Nepal, Welhausen continued his work with Alpha Phi Omega and volunteered at a food bank in Memphis as part of an ASB. Tipping joined Credo Choir, a Dallas-based music and community service organization, and she now volunteers with her local Humane Society. Cox, now a principal platform solution engineer at Salesforce, uses his talents to build apps for local nonprofits. And Neisig participated in an ASB to Hope Rising, a Houston-based child placement agency providing services to children rescued from human trafficking. She also helped organize this year's Big Event, a national day of service sponsored through UNT's Center for Leadership and Service.

"My only hope is that no matter what I'm doing or where I'm doing it, I'm making a difference in direct and indirect ways," Neisig says. "Whether that means volunteering with CLS or sitting and playing with kids who have been through the unthinkable, every little thing can mean the world to somebody."