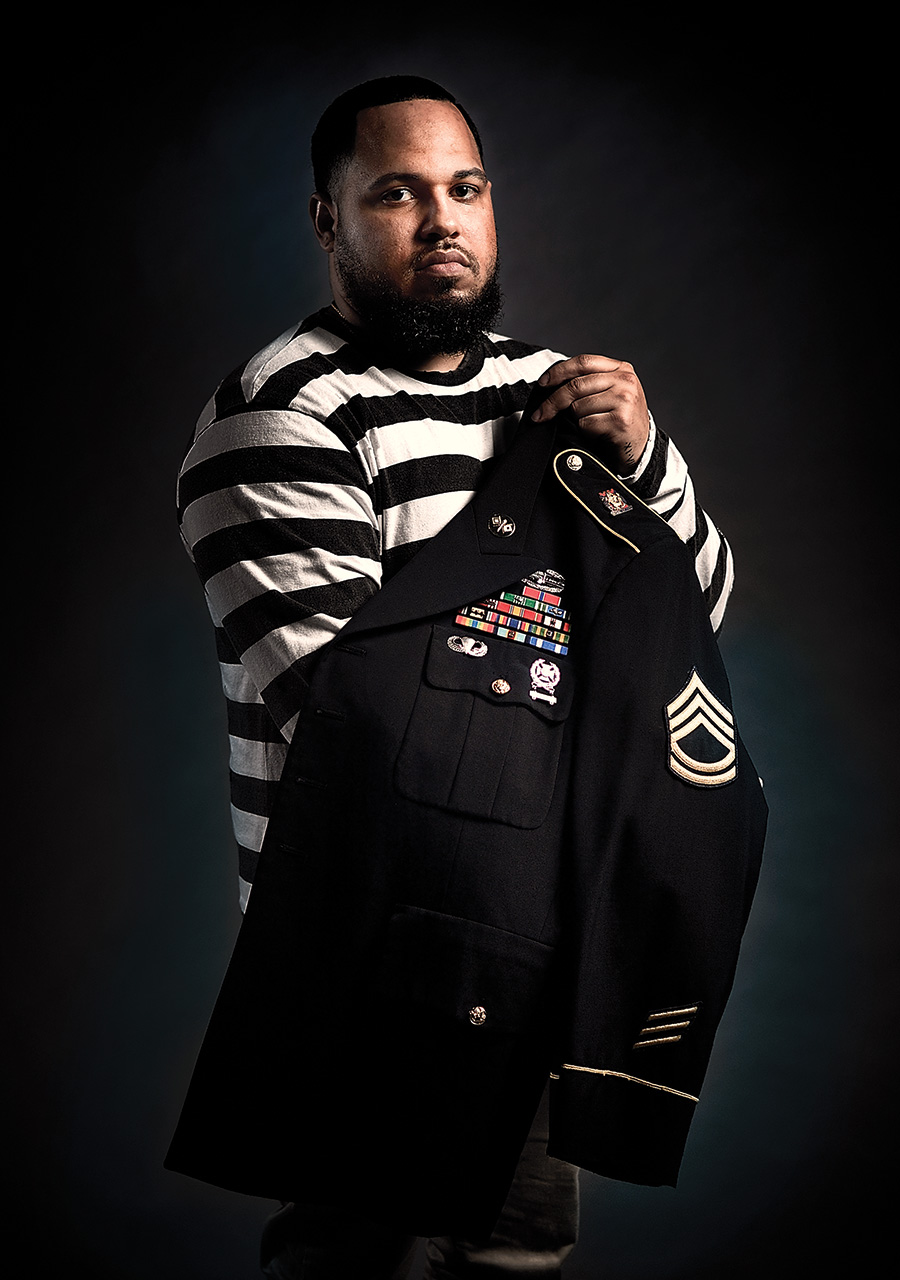

THE DEFENDER

Lehi Tollestrup ('18)

It's only eight letters, four syllables -- an ordinary jumble of consonants and vowels that belies an extraordinary strength. It's there, unflinching, in the faces of UNT alumni who have seen the worst: PET scans revealing cancer. Irreversible injuries. War. Poverty. It's in their determination to make the best of a bad situation, their inclination to survive and to serve, to raise their voices for artistry and for advocacy. In that one little word exist the stories of lives transformed. Just wait until you see tenacity in action.

Lehi Tollestrup ('18)

The sky that morning was clear, beautiful. The memories darker, uglier. Three deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan. The deaths of fellow soldiers. A deteriorating relationship. Lehi Tollestrup collapsed onto the grass and gazed at the heavens. He thought of how alcohol and pain pills had become his sole way to cope. He thought of the month's supply of sleep medication he'd just swallowed.

And then he thought, I'm ready.

He awoke two days later in a psychiatric hospital. For the first time in 11 years, he cried.

"I think if I would have had someone else who understood, I wouldn't have gotten to that place," Tollestrup says. "But when you're immersed in a culture where you're taught to be strong, how do you reach out?"

After his suicide attempt and a diagnosis of PTSD, Tollestrup finally sought help. He began working with a counselor at the Veteran's Administration who "guided me from the dark place back to the light." She read him the definition of vulnerability, encouraged him to express his feelings, never sugarcoated her advice.

Following months of treatment and medical retirement from the U.S. Army, Tollestrup departed Schofield Barracks in Hawaii for Denton, where he and his ex-wife had often visited family. One day, he used to think as he drove by campus, I'll go to UNT.

So he did. His Army career earned Tollestrup several credits toward a bachelor's degree in information science, and he pursued a minor in addiction studies. In fall 2018, he sent his former counselor an invitation to his graduation, along with another piece of news: He had been accepted into UNT's highly competitive graduate rehabilitation counseling program.

Though he's now engrossed in academic life, Tollestrup can always spot a veteran: It's the way they walk, certain words they use, the presence they command. When they enter a room, he says, they maintain an air of fearlessness.

He wants them to know it's OK to be afraid.

"With active-duty troops and veterans, you have this camaraderie -- you've learned to embrace the suck," Tollestrup says. "But sometimes you just need that person who can help stave off those dark thoughts. That's who I want to be. Seeking help for mental health is not weakness."

"Will I live long enough to see the birth of my son?"

It's not a question the 39-year-old ever expected to ask. He'd only visited the doctor as a precaution, to make sure his difficulty swallowing wasn't anything serious. "It's likely nothing," he was told. "But let's do a routine diagnostic just in case."

Steven Pettit didn't even make it to the parking lot before his phone rang.

Esophageal cancer. After a PET scan, the prognosis grew grimmer. Stage IV. Twelve months left.

"That kind of news, it just brings you to your knees," Pettit says.

With a 2-year-old son at home and another on the way, he had no choice but to pick himself up. He and his wife, Hillarie ('11), met with an oncologist who offered three pieces of advice: Pray. Do the treatments. See what happens.

Though doctors couldn't guarantee Pettit would be there for the birth of his son, he vowed he would, powering through chemotherapy and radiation that made him so sick he could barely eat or stand. Nearly one year after that first phone call, he received another: His cancer, as far as the oncologist could tell, was in remission.

"We were floored," Pettit says. "It seemed like a miracle."

He made the most of his remission, taking his family on a vacation to San Antonio and to Mean Green events. He filmed messages to his sons, extolling advice on everything from shaving to dating, just in case the cancer came back.

And then, last August, it did.

He took on six more rounds of chemo, and as the two-year anniversary of his diagnosis drew near, underwent surgery to remove part of his stomach and esophagus. In the months since, Pettit's continued to fight seemingly insurmountable odds -- more than 50 percent of those diagnosed with esophageal cancer die within two years -- but he hasn't fought alone. He's found support from UNT, his congregation and, most importantly, his wife and kids.

"I don't know if this is a prayer answered or just kicking the can down the road," says Pettit, who received a clear scan in May. "I've resigned myself to the fact that I probably know how I'm going to die -- it's a little scary to see the path in front of you. Still, you do the treatments even though they're worse than the disease. I will do anything it takes to be there for my children."

When 4-year-old Lilyan first heard she was leaving Guatemala for the U.S., she pictured mountains. First, the little girl imagined, she'd have to climb one to Mexico. Then she'd have to scale an even larger one to reach the land of opportunity.

There were no mountains. Instead, there were less physical, but no less daunting, barriers -- poverty, fear, a sense of not belonging.

"The journey was hard -- 1,500 miles, often by foot," Prado Carrillo says. "But that's the easy part compared to what awaits you as an undocumented person."

She learned to never complain of stomachaches since there was no insurance, to make do with little money or food, to fly under the radar. After her mom abandoned the family when Prado Carrillo was 5, she had to grow up even faster. By 15, she was practically working full time to help pay utility and grocery bills.

But there were good times, too, simple things like watching telenovelas with her dad as they ate dinner on the couch. It's the same couch she'd sit on as an elementary student when he woke her up at 4 a.m. because he had to leave for work. "Stay awake," he'd tell her. "If you miss the school bus, there's going to be a consequence."

"He showed me work ethic from the very beginning," Prado Carrillo says. That mentality translated to her academics, where teachers recognized her grit and sent her to leadership camps like UNT's Upward Bound. But after she graduated from Denton High, her undocumented status meant that attending a university wasn't an option.

Finally, 10 days before she turned 21, Prado Carrillo received her green card. She transferred from NCTC to TWU, where she pursued a degree in bilingual education. After two years as a teacher, she was selected as a national spokesperson for the Sallie Mae Fund. Then, a year later, she was hired as director of UNT's Emerald Eagle Scholars program, which assists highly motivated students who have financial need. Now Prado Carrillo -- who earned a master's in public administration from UNT -- serves as a bilingual/ESL specialist with Denton ISD, president of Denton County LULAC and a national speaker for the youth engagement company CoolSpeak, all to help those who are in the same situation she once was.

"I know what sharing this story means, I know what people will say: She broke the law, she didn't do it the right way. But if you have no money, no support, no sponsor, there is no 'right way' -- it will never be your turn," says Prado Carrillo, who became a citizen in 2010. "For a long time, I couldn't separate my status from who I was. It wasn't that my status was wrong, it was that I was made to feel that I was wrong. I want anyone else who feels that way to know their voice matters."

Sitting on the curb, beside the battered car she'd just crawled out of, Mason Bynes studied her left hand. It was bloody, but she could feel her fingers. She wiggled them.

At the hospital, the doctors placed her hand in a tourniquet. It wasn't until they opened it that Bynes saw her middle and index fingers had been irreparably damaged. "We can try an external fixator to save them," the doctors explained, "but it likely won't work." They suggested amputation.

"She's a musician," her parents told them. "This is her livelihood."

There wasn't much time to think. Bynes had suffered serious lacerations in the accident and was losing blood. A Type 1 diabetic, she needed surgery quickly to offset infection and plummeting blood sugar.

"It was unfathomable," she says. "I just had to make the decision and go."

When the freshman music student returned to UNT a few weeks later, she thought maybe the loss of her fingers was a sign she should follow a different path.

As a composition major, her voice was her primary instrument, but she also needed to write songs on piano and guitar. What used to come easy was now a battle, like passing the Piano Proficiency Exam -- a requirement for composition majors.

"I didn't know if I could finish school or be myself again," Bynes says. "The biggest challenge was figuring out who I am now."

After acquiring prosthetics to better play the piano -- purple fingers she views more as an instrument than an extension of her hand -- Bynes worked to re-engage herself as a performer, signing up for opera classes and a film composition course that refocused her career aspirations.

As time passed, her talent eclipsed any physical challenges. She won numerous accolades and composed short film projects under the mentorship of composers and UNT artists-in-residence Bruce Broughton and Drew Schnurr, and music for UNT's a cappella pop group, the Green Tones. This fall, she's attending the Berklee College of Music in Boston to pursue a master's in composition.

"After I went through my accident, I had a lot of soul searching to do," Bynes says. "It seriously made me consider how bad I wanted to be a composer. It forced me to ask -- how hard am I willing to work for this?"

It seemed like nothing at first -- a run-of-the-mill sideline tackle.

The fullback got up. The middle linebacker didn't.

A medevac landed on the field, and Nathaniel Little -- then a junior at R.L. Turner High School in Carrollton -- was loaded inside. Even atop a stretcher, he was more focused on the view from above than what had transpired below.

"Everyone around me was panicking, but I was like, 'Hey mom, we're on a helicopter -- do you see the city?" Little says.

Soon, the gravity of his injuries snapped into focus: He couldn't move his arms or legs, or even turn his head left to right. The irrepressible teenager who played football and basketball, wrestled, and was a member of the marching band and step team was now quadriplegic.

"I didn't know what I could take until I actually went through it," Little says. "I guess that's how life goes -- we all think that in certain situations we'd say, 'Life is over, woe is me.' But we can handle a lot more than we think."

To channel his energy, Little immersed himself in poetry. As a student, he was frequently praised for his writing, but it rarely meant more to him than a grade. Now it was a way to heal.

It also was a way to connect. Little, who graduated from UNT with a degree in strategic communications, decided it was time to share his words -- "to show people my heart." He figured there must be others in the North Texas region who also used poetry as an outlet and wanted to showcase their work.

"I was excited to help others find a voice and a platform," he says.

So Little hosted an online poetry competition, with the contest winners' writings appearing in his self-published book Nattyboy Blac Presents Poets of North Texas. His own work appears too, including his favorite poem, "The Wisdom Tree." In it, the titular object -- "a titan amongst trees" -- finds itself leveled.

"Before I got injured, I was this 6-foot, 215-pound linebacker who thought he was Superman," Little says. "I felt invincible. I thought that nothing could tear me down. But sometimes the tallest, strongest tree is turned into a stump. Yet that stump is still alive, still rooted in the ground. It had to endure something for people to truly see its lines -- its wisdom."