"I suffered from headaches, burning eyes and a dry nose," she says. "You see it, you feel it and you smell it. I have vivid memories of ozone action days, days it was recommended we not go outside. There were many of them."

It was in high school that she became interested in environmental issues and how to solve them. Now as an associate professor of geography and the environment, she is examining innovative ways to combat air pollution.

She is one of several UNT faculty members and alumni researching a problem that affects nearly the entire world. Air pollution can lead to a range of dangerous effects, from asthma to cancer to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease to weight gain. One in eight people will die due to the effects of air pollution, according to the World Health Organization. And air pollution can have negative effects on crop yields and forests.

"We should all care about air pollution because it affects our health and the ecosystems upon which we depend," Ponette-González says. "It can affect everyone in very real ways. It affects the economy. It affects our children."

And UNT researchers are determined to beat it.

"There are millions of solutions," Ponette-González says. "Our solution is to remove it from the air."

Anyone can be part of the solution. One of Ponette-González's projects involved different parts of the Denton community -- the UNT campus, city parks, homes and even Boca 31, a popular Latin food restaurant.

Those sites were used to help Ponette-González learn more about how trees can help fight air pollution.

"I like to think about what goes up in the atmosphere, what comes down, where it lands, when it lands and why it matters," Ponette-González says.

Anything can go into the atmosphere, good or bad -- soot, dust from the soils of West Texas, salt from the ocean, sulfur dioxide and microplastic -- and then fall out of the atmosphere naturally or in rain.

She wondered about the black carbon emitted from vehicles, wildfires and other sources. Where does the soot go? Industry uses scrubbers, such as spray towers, to clean out pollutants. Could trees and forests play a similar role and serve as urban air filters? Now in the fourth year of a five-year $534,263 CAREER Award grant -- the most prestigious recognition presented by the National Science Foundation for young researchers -- she is finding answers.

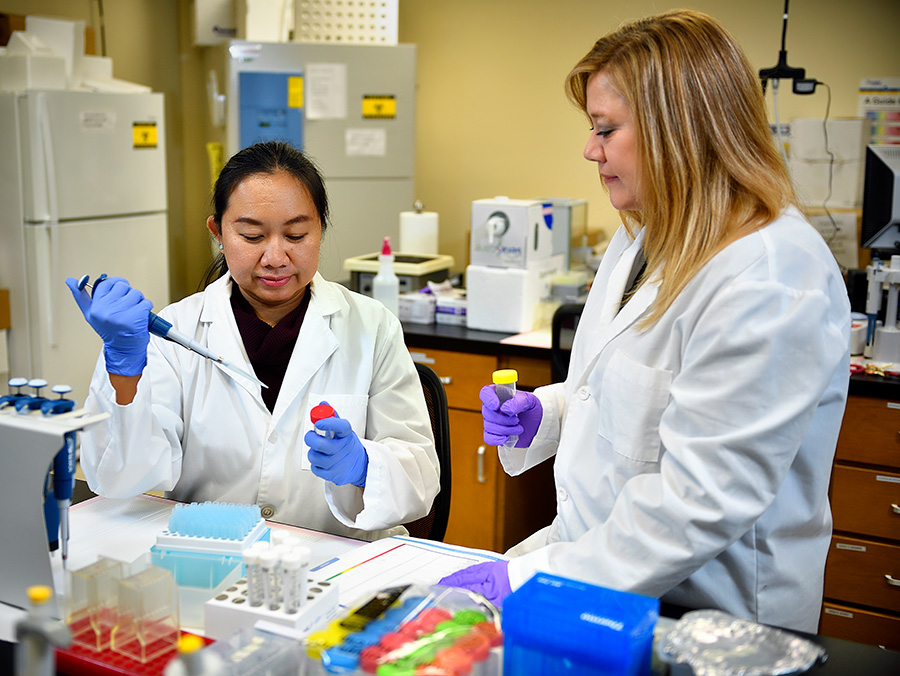

Her team gathered 400 samples of soot on leaves picked from live oak and post oak trees around Denton. After they collected the data, they conducted research in the Ecosystem Geography Lab.