Lasting Impact

UNT alumni from around the world came to honor Professor Emeritus G. Roland Vela.

December 1, 2014

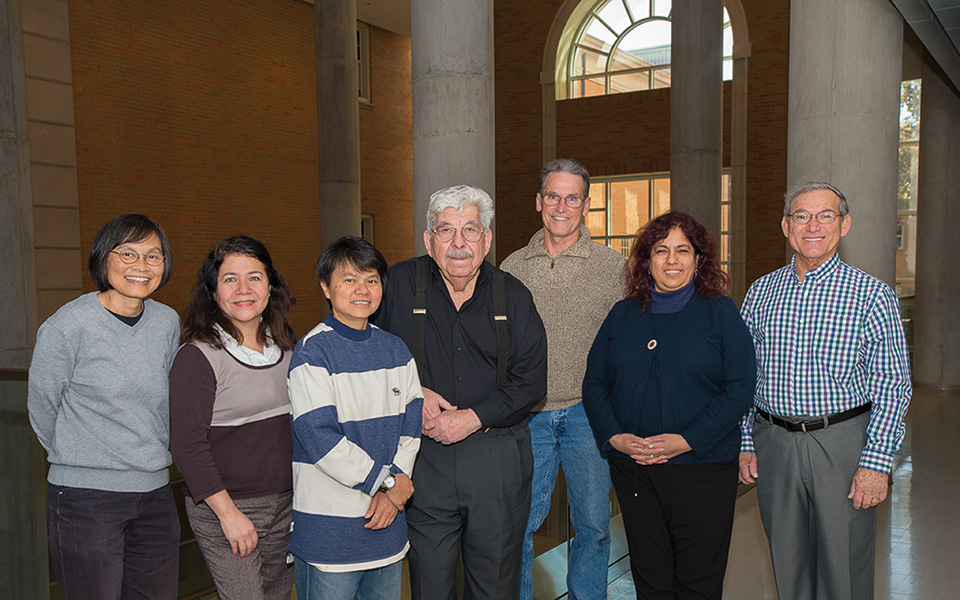

From left, Acharawan Thongmee ('99 Ph.D.), Roxana Bejarano Hughes ('97 M.S.), Patamaporn

Sukplang ('00 Ph.D.), Professor Emeritus G. Roland Vela, John Rainey ('71 M.S.), Guadalupe

Virginia Nevárez-Moorillón ('95 Ph.D.), Joel Escamilla ('80 Ph.D.). (Photo by Ahna

Hubnick)

More than 20 microbiology alumni returned to campus from labs and universities in Thailand, Taiwan, Mexico and across the U.S. to honor their mentor, Professor Emeritus G. Roland Vela, in November. Vela, who joined the UNT microbiology faculty in 1965, supervised 20 Ph.D. students and 40 master's students before retiring in 2000.

After graduating, Joel Escamilla ('80 Ph.D.) crossed paths with his major professor a few times during his career as a microbiologist with the U.S. Navy, and this year he decided to arrange a reunion of Vela's students.

"See all the wrinkles on my face?" Escamilla asks. "You begin to think of acknowledging those who help you along the way, and it became obvious this was something we should do."

He and other organizers were able to track down many of the graduates and invite them back to honor Vela, who describes it as "humbling."

"I'm overwhelmed by their kindness. I can't believe they all remember me," he says, to a chorus of laughter.

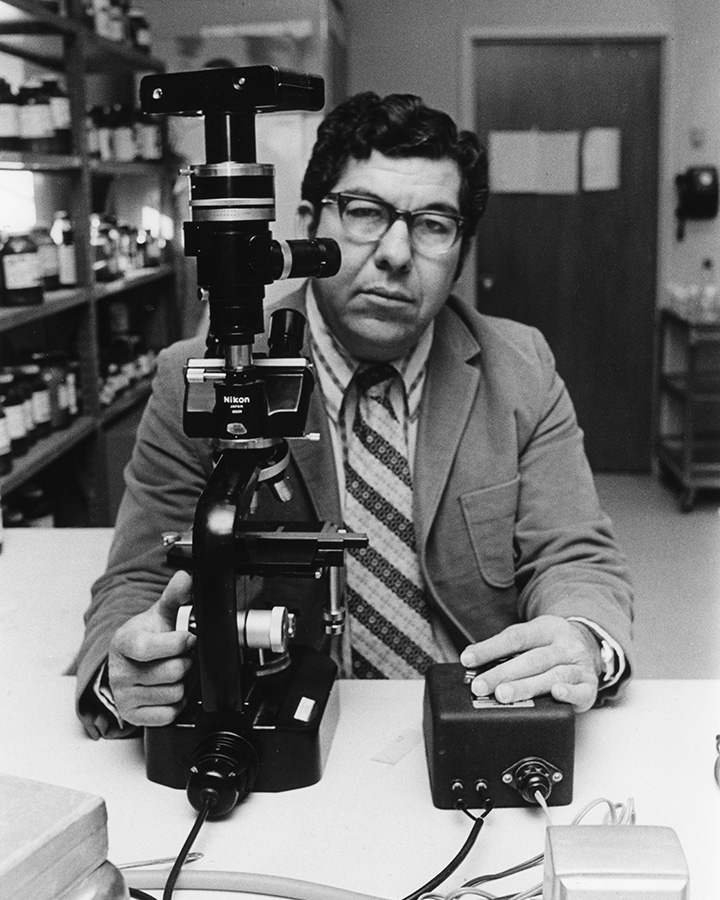

G. Roland Vela

Paenibacillus velaei

Patamaporn Sukplang ('00 Ph.D.), director of biomedical sciences graduate programs at Rangsit University in Thailand, says they could not do anything less.

"Dr. Vela was my mentor, not just in microbiology but in life. I was far away from my home in Thailand and he welcomed me and was so kind to me," she says. "He supported me in every activity I have been involved in and I know that he will always do his best for all of us."

Sukplang has the distinction of being Vela's last Ph.D. student. She also was one of four students to conduct research on a bacterium he had found earlier in his career.

Guadalupe Virginia Nevárez-Moorillón ('95 Ph.D.), graduate studies coordinator in the School of Chemical Sciences at the Universidad Autónoma de Chihuahua, first studied the bacterium from soil samples Vela collected more than 30 years earlier.

Roxana Bejarano Hughes ('97 M.S.), instructional lab supervisor in UNT's biology department, studied the bacterium's distribution.

Acharawan Thongmee ('99 Ph.D.), head of the microbiology department at Rangsit University, continued the investigation and suggested the bacterium be named for Vela -- Paenibacillus velaei.

"It differs from other bacteria we know," she says of the new species, which is surrounded by an unusually large capsule.

For her dissertation, Sukplang characterized the polysaccharide the bacterium produces, which may have applications in the food and pharmaceuticals industries.

"They did a lot of work," Vela says of the students' research, and jokes that he would tell Sukplang, "Just finish so I can retire."

Attending the reunion were, from left, standing, Patamaporn Sukplang ('00 Ph.D.),

Acharawan Thongmee ('99 Ph.D.), Guadalupe Virginia Nevárez-Moorillón ('95 Ph.D.),

Jung Fu Wu ('77, '78 Ph.D.), Wayne Barnes ('72 M.S., '79 Ph.D.), Joe LaBay ('71, '74

M.S.), Massoud Mahmoudi ('86 Ph.D.), Luis A. Rodriguez ('86, '88 M.S.), Juan Sanchez

Yañez (whom Vela directed for his 1992 Ph.D. from the Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo

León), Miguel Castro ('96 Ph.D.); seated, Anthony Gonzalez ('82 Ph.D.), John Rainey

('71 M.S.), James Gray ('66, '67 M.A.), Emma Lamar Codina-Vela, G. Roland Vela, Joel

Escamilla ('80 Ph.D.), Solomon Alade ('80 Ph.D.) and Charles Chang ('80 Ph.D.). Not

pictured: Roxana Bejarano Hughes ('97 M.S.), Gerald Cagle ('69 M.S., '72 Ph.D.) and

Lichu Yao Hsu ('75 M.A.).

Independent research

Vela says he and his family came to Denton because UNT was offering the best salaries in the country as it became a full-fledged university focusing on research and doctoral work.

"UNT was a great place to work with a lot of freedom to do what you wanted to," he says.

That was a philosophy he passed along to his students.

"What I learned from Dr. Vela was the importance of having freedom and responsibility in research," Nevárez-Moorillón says. "He would tell me to go do the research and see what results I would get. I would have several weeks of independent study. He didn't expect a report every day."

She brings that experience to her job now.

"I left UNT 20 years ago, but in tutoring and mentoring my students, I realize I'm just like Dr. Vela was with me."

Vela says he had good reason for allowing his students so much independence in their work.

"I often said, 'I could do it, but I want you to find out for yourself. I don't teach assistants -- I teach directors.'"

Lasting impact

Vela's impact on master's students also was lasting. Hughes vividly remembers his help when the time came for her to defend her thesis. She was pregnant and had been put on bed rest.

"I had to defend by September or I was going to lose some credit hours," she says. "Dr. Vela said, 'Don't worry, we'll come to your house.'"

So Vela made a housecall, along with faculty members Gerard O'Donovan and Scotty Norton.

"Dr. Norton had a cold so he stayed outside the door," Hughes says. "I was on the couch and we were passing my presentation slides around to view. I'm very grateful they did that for me. Otherwise, I would have had to stay another semester."

Her son, now 17, attended one of the dinners during the reunion.

"We had him stand up and everyone clapped," she laughs.

John Rainey ('71 M.S.), a master's student at a time when marches and protests were common on campus, says Vela had "a stabilizing effect" on his life.

"I was a hippy dippy guy of the '60s, with long hair and cutoffs," he says. "Dr. Vela was unshakeable. I'd tell him I had to go participate in a demonstration, and he'd say, 'OK.' He knew the research would get done, and we knew failure was not an option in his lab."

For his thesis, Rainey researched a system to remove phenols from the wastewater of a wood treatment plant. He went on to work in several industries after his studies with Vela.

"I felt like I received a key to the universe when I walked out of this university," Rainey says.

Distinguished career

Over his distinguished career, Vela has been a Fulbright lecturer, a fellow of the American Academy of Microbiology, an industry consultant, an expert witness and a textbook author.

His research on bacterial physiology and nitrogen-fixing bacteria has been recognized nationally and internationally, and he has lectured in many parts of the world, including Mexico, Colombia, Argentina, Belgium and England.

Vela also served on the Denton City Council and numerous other boards and commissions and is the namesake of a new Denton soccer complex, the G. Roland Vela Athletic Complex. He was named one of the top 100 Texas Latinos of the 20th century by Latino Monthly magazine.

His students remember that Vela always told them, "Go get a higher position than I have," and they have made him proud. His Ph.D. students have held leadership positions at Alcon Labs, the Mayo Clinic, Cornell and Tulane as well as other universities around the world.

But Vela's accomplishments in the field and his role in his students' success may never have come about if not for a financial decision he made as a college student. He enjoyed studying genetics, chemistry, history and English literature, and by his junior year, he was told he had to pick a major. About that time, one of his college friends who was soon heading off to dental school had to buy an expensive textbook for a bacteriology course.

"I was leaning toward majoring in genetics or chemistry. I wasn't interested in bacteriology," Vela says. "But my friend said if I split the cost of the textbook with him, I could keep it. I took the class and I loved it."

Reunion days

The alumni at the three-day reunion enjoyed comparing stories about Vela and their UNT days, touring the newest campus labs and visiting with their professor and his family. UNT faculty past and present -- Sam Atkinson and Don Smith from the biology department, Gene Wright from the English department and Anthony Damico from the foreign languages department -- had a part on the program.

And Nevárez-Moorillón, Hughes, Thongmee and Sukplang presented the story of Paenibacillus velaei.

They were warned to keep it simple, though.

"If it gets too technical," Vela joked, "I'll go to sleep."