Power of Place

UNT adds to state-of-the-art facilities that set the course for learning.

November 24, 2009

Buildings, campus create memorable environment for learning and experiencing life

View of the UNT campus.

Paul Croteau (’88) with his wife, Sue Friesenhahn Croteau (’89) (Photo by Gary Payne)

Memories of living in Bruce Hall as music students are powerful for Sue Friesenhahn Croteau (’89) and Paul Croteau (’88), drawing them back to UNT through the years. Most recently, they traveled from San Antonio to re-create the 25th anniversary of their first date, which began in the residence hall’s lobby windowsill Oct. 1, 1984.

“This is a special place because we started our life together here,” Paul says. “The campus will always be home, pulling us back like a magnet.”

After they found their carved initials — “S & P” — in the wooden railing of the staircase and the front yard’s concrete border, Sue’s eyes welled with tears.

“These pine trees were just babies when we were here, and now look at how tall they are,” she says.

UNT’s architecture and landscapes are integral elements of the university’s identity and history, often playing a role in the experiences of students, alumni, faculty, staff and community members and helping them form just as much of an emotional connection with the campus as with the people they meet.

Interactive campus map

While the Croteaus’ memories remain timeless, the UNT campus continues to evolve to meet the needs of future generations. Enrollment has increased by more than 37 percent in the last decade, reaching more than 36,000 students this fall, and the physical space for the UNT System’s flagship campus now stretches across several sites in Denton. This expansion has enabled the university to build on its rich traditions and interdisciplinary learning opportunities while still offering a welcoming environment.

Smart growth

The 47,000-square-foot Athletic Center houses training facilities, offices and meeting

rooms. (Photo by Jonathan Reynolds)

University leaders have been methodical in efforts to incorporate history while developing a new round of state-of-the-art learning facilities that meet the needs of modern students.

Following a carefully thought-out master plan, UNT is managing its growth while ensuring the campus of tomorrow offers students the best possible learning space, President Gretchen M. Bataille says.

“If you look at America’s great public research universities, you’ll see that they have the three A’s in common: great academics, great arts and great athletics. All are key to a vibrant university community and continued growth. And all require great facilities,” Bataille says. “At UNT, we are striving to be excellent in everything we do, and our facilities are an important part of achieving that.”

In all, the 119-year-old campus now has 165 buildings of traditional, post-traditional and contemporary design. These include 14 residence halls, the Mean Green Village with its Athletic Center and surrounding athletic fields, and a nearly 290-acre Discovery Park research facility. The next facilities slated to open are the Life Sciences Building, the Business Leadership Building and the Mean Green’s future football stadium.

The Murchison Performing Arts Center features premier venues and talent. (Photo by

Jonathan Reynolds)

“UNT is an economic engine for the city,” says Linda Ratliff (’96), director of economic development for the city of Denton. “The university impacts Denton with the number of students, faculty and staff who spend money here. It’s the largest employer in the city. And it draws community members from the region to attend cultural and athletic events.”

For example, the Murchison Performing Arts Center with its premier venues regularly hosts world-class performances by guest artists, faculty and students. The Rafes Urban Astronomy Center continues UNT’s decades-long practice of offering free stargazing to the public.

And the Elm Fork Heritage Museum and Education Center welcomes 15,000 school-age children each year for field trips and science programs.

Students visit the Rafes Urban Astronomy Center. (Photo by Jonathan Reynolds)

“We are beginning to see undergraduates in environmental science classes who first came to UNT on these field trips,” says Brian Wheeler (’97), assistant director of Elm Fork education.

UNT’s pledge to create an all-encompassing student experience requires an understanding that learning opportunities occur in many places. Every inch of campus — from a park bench near the restored fountain to a new building or laboratory — is designed to preserve the traditional UNT experience while ensuring that all students have the best possible environment.

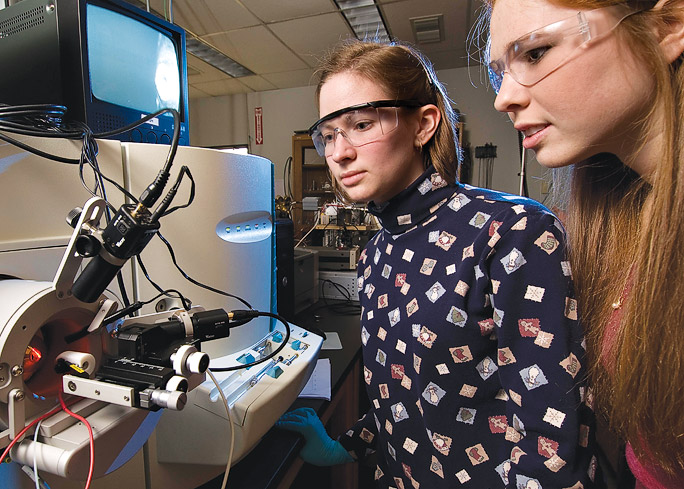

Students conduct research in the Chemistry Building, which opened in 2004. (Photo

by Jonathan Reynolds)

Learning opportunities

When Masters Hall, named for W.N. Masters, former head of the chemistry department, opened in 1950, the 58,000-square-foot building featured the latest technologies and lab space to accommodate a growing post-World War II student body.

Bill King (’51), a biology and chemistry major who went on to earn a degree from Northwestern University Medical School, remembers helping move in equipment and teaching the first lab in the new facility.

“It included a big projector screen in the lecture hall for presentations. It was state-of-the-art for the times,” King says of the structure now being replaced by the new Life Sciences Building — another state-of-the-art facility.

Discovery Park is UNT's nearly 290-acre research facility, home to the College of

Engineering and the College of Information. (Photo by Jonathan Reynolds)

UNT’s continued commitment to cutting-edge research begins with space, which faculty researchers say is synonymous with creating opportunities. In 2003, UNT purchased a former Texas Instruments facility to create Discovery Park, now home to the College of Engineering and College of Information. The 500,000-square-foot facility is developing as a business incubator and research park, with a new clean room and a unique combination of high-powered microscopes that give faculty members the ability to conduct research leading to the creation of stronger materials and smaller devices.

“We have talented faculty members and students partnering with industry leaders in many research arenas,” says Vish Prasad, vice president for research and economic development. “UNT is poised to take the lead in technology transfer, commercialization and incubation, which will give Discovery Park national and international visibility.”

Ratliff agrees.

“Future plans for Discovery Park will set Denton apart, because while some cities have a university, not many have research parks,” she says. “The city will be known as a leader in research and development.”

Willis Library contains more than 6 million cataloged holdings. (Photo by Jonathan

Reynolds)

The university also recently added a $2.2 million centralized high-performance computing facility. One of the premier facilities of its kind, it will provide a 10-fold increase in computational power, attracting top faculty and grants and enhancing research.

William Moen, associate professor of library and information sciences, and a team from the UNT libraries and the Department of History plan to use the facility for analyzing more than a million pages of digitized historical newspapers.

“This resource will allow us to analyze patterns of the migrations of ideas, people and diseases,” Moen says. “It will give historians a new way of looking at these things.”

The Pohl Recreation Center (left) is a 138,000-square-foot state-of-the-art facility.

Chestnut Hall (right) houses the Student Health and Wellness Center and other services.

(Photos by Jonathan Reynolds)

Sorority Row, a connected complex containing seven houses, includes two added this

fall. (Photo by Li Fan)

In addition to new academic and research facilities, the university has added buildings that house services catering to student needs. In the past 15 years, UNT opened Chestnut Hall, the Eagle Student Services Center and the Pohl Recreation Center, as well as six new residence halls that paved the way for the creation of Sorority Row — seven connected houses, including two added this fall. UNT has 14 fraternity and sorority houses with about 350 residents. And across campus, more than 5,500 students live in the various residence halls.

The Croteaus say they always will have fond memories of living on campus.

“We’ll always remember watching the Star Wars trilogy in the Lyceum, listening to jam sessions emanating from the Music Building and sledding down the parking lot after ice storms,” Paul says. “We bleed green. This is our house.”

Being green

The Environmental Education, Science and Technology Building was green before LEED

certification existed. (Photo by Angilee Wilkerson)

UNT’s newest construction projects are preserving the traditional campus experience while turning a page in the university’s history with sustainable building.

Last year, UNT became the first large public university in Texas to sign the American College and University Presidents Climate Commitment, promising to achieve at least LEED Silver certification on all new buildings. Already, the university is surpassing its own expectations. The new Life Sciences Building — targeted to open in June — is expected to achieve LEED Gold certification, along with the Business Leadership Building and new football stadium.

There’s no better building for UNT’s first LEED certified facility, says Art Goven, chair of the biology department.

“By using an open lab concept with large bench research labs shared by multiple principal investigators and graduate students, the space itself will promote interaction and collaborative research projects,” Goven says. “But we’ve also taken advantage of every architectural and energy advancement. It just doesn’t get any better than this.”

A rendering shows the Life Sciences Complex, which will feature thousands of square

feet of labs. (Rendering by Perkins and Will)

The 87,000-square-foot building replaces Masters Hall. Connecting to the existing Biology Building to create the Life Sciences Complex, this $33.4 million modern research facility with shared equipment rooms, a roof-top greenhouse, fresh and salt water tanks, and 24,000 square feet of labs was thoughtfully planned to support UNT’s multidisciplinary research goals.

It also will feature north-facing labs that use natural light, a 20,000-gallon rainwater collection tank nearby to water surrounding shrubbery, and cost-effective lighting and vent hoods that cycle to rest mode to cut costs and lower the university’s carbon footprint.

It was the topnotch research space that drew Pudur Jagadeeswaran, professor of biology, to UNT four years ago. His zebra fish gene mutation research has applications to the study of human diseases. While the current labs are the largest in Texas, the size of the tanks in the new building will make the UNT facility the largest among university labs in the nation.

“Right now, my lab is a Toyota, but soon it will be a Cadillac,” he says. “It’s a fantastic thing. With more tanks, more genes can be identified.”

In addition to new environmentally friendly buildings, UNT will work toward achieving LEED certification for campus mainstays.

“We have to strike a balance with what we’re trying to accomplish with new builds and existing buildings,” says Todd Spinks (’04, ’06 M.A., ’09 Ph.D.), director of UNT’s Office of Sustainability. “‘We Mean Green’ is more than a slogan here. We want to create a sustainable university for generations to come.”

Building partnerships

College of Business Dean O. Finley Graves presents a model of the Business Leadership

Building. (Photo by Mike Woodruff)

UNT’s facilities also are bridges to the outside world. The new 180,000-square-foot Business Leadership Building — slated for completion by June 2011 — will accommodate at least 8,000 students, giving the College of Business open spaces for interaction between students, faculty and industry leaders.

Designers have included a trading room, an atrium, an Internet café and numerous study and tutoring rooms designed for collaborative learning and community business partnerships. Faculty offices will not be organized by department but intermingled to foster interdisciplinary research. In addition to videoconferencing capabilities, some graduate-level classrooms will provide executive education for outside business.

“The contemporary design is stunning but also completely functional. It encourages interdisciplinary study and outside business mentorship,” says O. Finley Graves, dean of the college. “It is a building that will greatly enhance the quality of business education at UNT.”

A rendering shows the new stadium, slated to open by fall 2011. (Rendering by HKS

Inc. Architects)

The new football stadium will provide another window into the university. Set to open in 2011, it will be the centerpiece of UNT’s Mean Green Village and will serve the entire North Texas region as a venue for outdoor concerts, community events, high school games and band competitions, in addition to hosting UNT games and events.

Plans for the multi-purpose facility include increased tailgating space, capacity for about 30,000 fans, luxury suites, an amenity-filled club level, a Spirit Store and a Touchdown Terrace that will serve as a hospitality area for large groups.

The stadium will replace 57-year-old Fouts Field and will be the first collegiate football stadium designed by award-winning HKS Inc. Architects, the firm that designed the new Dallas Cowboys stadium.

“I’ve waited for years to build a new stadium for the Mean Green,” says Jordan Case (’81), chair of the volunteer committee raising private donations for the facility and UNT Athletic Hall of Fame member. “Our new stadium will be a spectacular demonstration of UNT’s commitment to first-rate athletics.”

Honors Hall, the residence hall exclusively for Honors College students, opened

in 2007. (Photo by Jonathan Reynolds)

More than buildings

Honors Hall features study rooms with library access, a computer lab and music practice

rooms. (Photo by Jonathan Reynolds)

UNT’s facilities are more than a set of buildings. A university should have meaningful places that symbolize the power of the institution, says Gloria Cox, dean of the Honors College who worked with architects to design Honors Hall in 2007.

“A university without traditions is impoverished,” says Cox, adding that the college places a brick in the sidewalk at Honors Hall for each of its graduates. “This adds to the power of the place. It’s highly symbolic, and one day these graduates will bring their children and grandchildren to see their brick.”

One of the older landmarks on campus, the Gazebo designed by O’Neal Ford, was a gift from the class of 1928. It stands between the Auditorium and Language buildings with its wrought-iron detail, a witness to years of memories.

Understanding the importance of place, UNT has focused on creating student gathering places and spots for quiet reflection such as the Shrader Pavilion, Goolsby Chapel and the Onstead Plaza and Promenade in the last decade.

Freshman Torie Watson says she discovered a special place in front of the Art Building to contemplate during her first week of school.

“Sitting on a swing in the shade, I took in the trees, the dragonflies, a squirrel running by,” she says. “It was a peaceful spot where I could think. And I realized that’s a big part of college, having time to discover who you are and who you’re going to be.”