Redefining Culture

UNT alumni use creativity to tap into America’s consciousness.

August 25, 2018

Before she became a gothic literary icon, Anne Rice was a college student in Denton, soaking up a world of new experiences.

While Rice (then known as Anne O’Brien) and her future husband, Stan, briefly attended North Texas in the early 1960s, they listened to the lab band at the student union and hung out with fellow students who were writers, artists and musicians.

“It was a wonderful atmosphere of creativity,” she says. “We really felt like you could do wonderful things, and that was shared by other people.”

As a place that breeds creativity, UNT has influenced a number of individuals who have not just gone on to fame, but whose work has left a distinct imprint on popular culture.

Rice ushered in a new genre of gothic literature, turning vampires into heroes, and recently has been making a mark in Christian literature. Fellow alum Mickey Jones played drums for Bob Dylan before becoming a recognizable character actor. And Ron English (’84) creates art that turns pop culture on its head.

The university also has been home to other inventive individuals, like School House Rock composer Bob Dorough (’49), “Over the Hedge” illustrator T Lewis (’76) and the late Eraserhead actor Jack Nance. UNT continues to foster creativity and offers students the chance to study its impact through classes such as “Mythic Rhetoric of the American Superhero” and “Pop Music in American Culture.”

The university offers the ideal environment to allow students to stretch their minds while tapping into America’s cultural consciousness, says Shaun Treat, assistant professor of communication studies who teaches the superhero class.

“UNT provides a learning atmosphere that promotes outside-the-box thinking,” he says.

Although popular culture is defined by mass appeal, it shouldn’t be discounted, says Lynn Bartholome, longtime member and former president of the Popular Culture Association. After all, William Shakespeare and Charles Dickens were pop culture icons of their day, she says.

“Popular culture is a barometer of what’s important to us — what we fear, what we love, what we worry about,” says Bartholome, an associate professor of English and philosophy at Monroe Community College.

Anne Rice

Anne Rice (Photo by Renée Vernon)

For Rice, a girl schooled in the Catholic church, college was a revelation.

“I opened myself up to literature and modern art, things that I was not allowed to explore as a child with a religious upbringing,” Rice says.

She started her college career at Texas Woman’s University but later studied English at North Texas, joining Stan, who became a well-known poet. The couple married at the home of one of Stan’s English professors, Jesse Ritter, before moving to California to find jobs and finish college.

But Denton left such an impression on Rice that it made an appearance in her novel The Witching Hour. It was in California that she wrote her first book, Interview With the Vampire, after losing her young daughter to leukemia.

“People responded to its originality, language use and poetic prose,” says Rice, adding that the 1976 book wasn’t successful until the paperback was released. “Readers also responded to the emotions of characters, despite the fact that they were vampires.”

The book catapulted again into the public eye in the 1990s when it was made into a movie starring Brad Pitt and Tom Cruise.

Rice, who to date has published nearly 30 books, wrote a dozen books about vampires, paving the way for vampire-themed fare like the Twilight series. After a long detour from faith, she returned to the church in 1998 and decided to write only about Christianity in 2002, the same year Stan died of cancer.

But Rice has not renounced her earlier works, saying the books and characters have a strong moral compass. Vampires are the perfect metaphor for outsiders, she says.

Nor has she conformed to the devotional mold of Christian literature. She continues to write in a modern vein with an exacting eye for historical details. She now is writing a Christian thriller, which, like all her books, is geared for the mainstream.

“I wanted to write really good novels that anyone could pick up and read and that the most devout Christian would find historically correct,” Rice says.

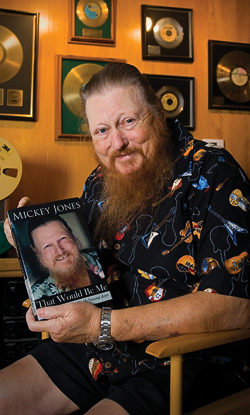

Mickey Jones

Mickey Jones (Renée Vernon)

Even by his own admission, Mickey Jones is not a household name. But chances are he’s shown up in your household.

He’s the surly biker in the Breath Savers commercial, the one with the fresh breath that the elderly lady has been enjoying since 96th street. He is the mechanic who bilks Chevy Chase of all his money in National Lampoon’s Vacation. And he is the guy banging away on the drums on Bob Dylan’s Live 1966 album.

Jones, who started at North Texas in 1959, lived in West Hall and joined Delta Sigma Pi, all the while playing drums in the Trini Lopez band. Bidden by his parents, Jones studied business so he would “have something to fall back on if the music thing didn’t happen.”

But music did pan out. By 1961, Jones was touring Europe with Lopez. He spent three years with Johnny Rivers of “Secret Agent Man” fame before ending up as drummer for Dylan, playing on the seminal tour in which Dylan clashed with fans over his changing style.

“They hated our guts because Bob was a purist when it came to the folk genre, and for him to pick up an electric guitar and start playing rock and roll — we got booed,” Jones says.

Later, Jones played with Kenny Rogers and the First Edition at a time when the band turned down Woodstock.

After 17 gold and platinum albums and nearly 40 trips around the world, Jones became an actor. He has since become instantly recognizable, with biker roles in films such as Sling Blade and a standing role as Pete Bilker on the television show Home Improvement. People often ask him to recite his famous line from Vacation: “All of it, boy.”

“It’s pretty cool because you know someone has seen your work and thought it was good enough to talk to you about or remember,” Jones says.

Ron English

Ron English (Courtesy of Ron English)

English crashed his way into popular culture, co-opting billboards and subverting the corporate message to get people to think about what they are consuming.

He got attention during the 2008 presidential campaign when he created his “Abraham Obama” portrait for posters and murals that melded the faces of the presidential icon and the presidential hopeful. The Obama campaign commissioned the piece, though English decided on the image.

He studied photography at UNT with Brent Phelps, professor of studio art, and Skeet McAuley, former professor, who both served as his mentors and as role models of working artists. They coaxed the shy artist out of his shell.

For English, college was a springboard from his working class background into the world of art. And even though he was a photographer, he approached it with an artist’s eye, taking photos from unusual perspectives and experimenting with trickery in his landscapes.

“My art wouldn’t be what it was if I hadn’t been a photography student first,” English says.

It was the political activists he later lived with in Austin who made him rethink his billboard art.

“They thought it was interesting that you give away art to the public,” he says. “They said you should use it as a message.”

English is still influenced as much by the people around him as he is by his own personal philosophy.

And although he now calls himself a pop artist, he was first turned off by pop art’s superficiality. But in his hands, billboards of Bart Simpson and paintings of Marilyn Monroe are social commentary.

“Pop art can either be art that is popular or art that comments on the popular culture. And at its best, it’s both,” English says. “The role of the artist is not to answer questions, but to ask the questions and to get people to think about things.”