From conducting research to assisting patients, UNT alumni are finding ways to attack one of the world's greatest enemies.

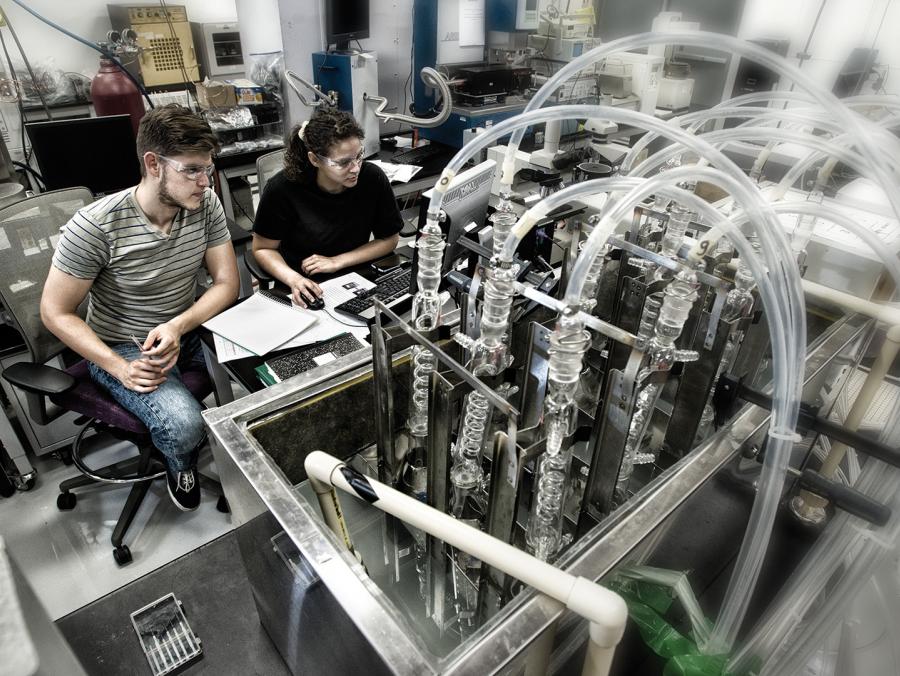

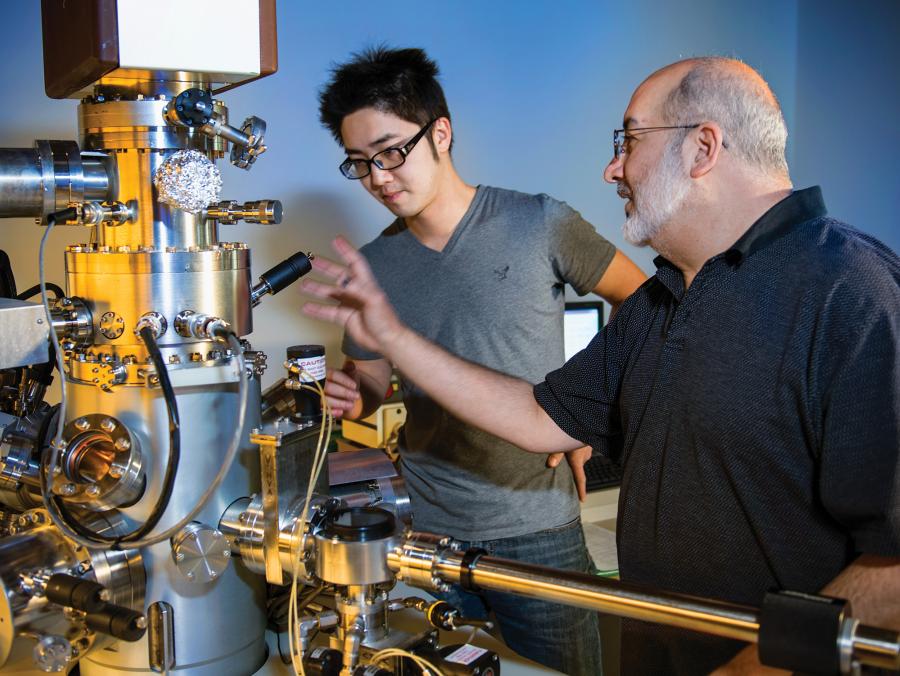

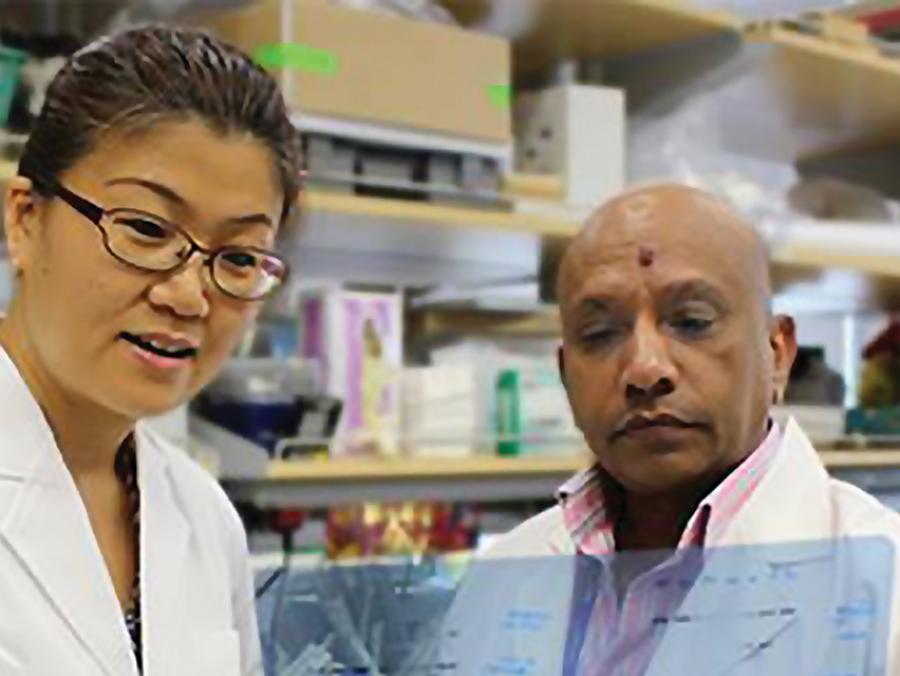

In a laboratory at UNT, Sreekar Marpu ('11 Ph.D.) is on the hunt to kill cancer. The research assistant professor of chemistry is working to develop optical sensors that have the ability to differentiate deadly cancer cells from normal benign cells. He also is researching biocompatible nanomaterials that help obliterate cancer cells.

Other UNT faculty have made their own innovative findings, from discovering a protein that could be the cause of some breast cancers to creating a device that can detect cancer in its early stages.

UNT alumni, too, are fighting one of the leading unsolved health crises of our time. Some are physicians and medical professionals who diagnose patients and set up radiation treatments. Others are advocates who conduct research on helping underserved populations and assist patients and their families in securing the financial and emotional support they so desperately need. The work is of dire importance. More than 1.7 million new cancer cases surface each year, and more than 600,000 people will die from the disease in 2018, according to the American Cancer Society.

For many, the fight is personal. Marpu was inspired to conduct this research by his Ph.D. advisor, Zhibing Hu, who was a Regents Professor of physics. Marpu describes Hu as a "great, inspiring personality" ahead of his time as a researcher and says he also encouraged students to learn from their failures.

Hu died of leukemia in 2012. Oussama El-Bjeirami ('06 Ph.D.), one of Marpu's colleagues who was a postdoctoral researcher in chemistry at UNT, died of stomach cancer that same year.

"People around each of us have been sacrificed to this disease," Marpu says. "They remind us we must do something to help find a cure."

Marpu's mind is constantly considering the next new project.

"What will happen if I mix these chemicals or reactants together?" he asks.

This curiosity leads him to try 10 experiments per day. As a graduate student, he often slept in his lab so he could watch over and monitor the chemical reactions. He doesn't get discouraged if one of his studies fails, just looks ahead.

"If one reaction works, it will give me a new project," says Marpu, who first came to UNT in 2005 as a chemistry major before switching to materials science and engineering.

His experiments as a graduate student also got him thinking about cancer cells, which in the early stages are often difficult to diagnose or differentiate from healthy tissue. Then, once the disease is diagnosed, it is difficult to target and kill cancer cells without affecting healthy cells and causing side effects like those that can come from chemotherapy.

Marpu's research focuses on the creation of biocompatible gold nanomaterials and optical sensors. The optical sensors have the ability to differentiate between healthy and cancerous cells based on differences in optical properties, while the gold nanomaterials have the capacity to absorb light and generate heat that eventually can be selectively directed to kill the cancer cells.

Though such heat-generating nanomaterials were known before, Marpu and his team are working to make these biocompatible and viable to the human body with minimal to no side effects. Current state-of-the-art nanomaterials with similar properties suffer from toxicity issues, a challenge this research is addressing.

Marpu's work on the project with Mohammad A. Omary, University Distinguished Research Professor of chemistry, physics, and mechanical and energy engineering, has resulted in one patent with another pending. They have obtained materials from collaborators at the National Cancer Institute's Laboratory of Cell Biology to explore the possibility that the UNT nanoparticles might overcome some of the defined mechanisms of drug resistance in cancer.

Other UNT researchers also are looking at innovative ways to fight cancer. Ron Mittler -- professor of biological sciences and researcher in UNT's BioDiscovery Institute, one of the university's Institutes of Research Excellence -- is part of a team from two countries and several universities that has made major discoveries. The team connected a single protein to some of the most lethal types of breast cancer and then found a way to suppress the protein and stop tumor growth. They are now conducting clinical trials.

Chemistry professor G. Andrés Cisneros and doctoral student researchers Alice Walker and Pavel Silvestrov have discovered and characterized a novel genetic mutation associated with prostate cancer in African American men. Francis D'Souza, University Distinguished Research Professor of chemistry, is collaborating on a chemical sensor device that could detect cancer in its early stages, giving patients their best opportunity for recovery.

Biostatistics professor Xuexia 'Helen' Wang has studied young cancer patients' health records at several hospitals and the Children's Oncology Group to determine whether certain genes are behind later health problems connected to chemotherapy and radiation. And history professor Constance Hilliard has pioneered the field of "African evolutionary history," which explores the intersection of genetic adaptations and ecological environments. She uncovered the link between an ethnic-specific genetic variant and black Americans' unusually high susceptibility to a certain class of cancers.

Su Gao, dean of the College of Science, says UNT's work in the fight against cancer demonstrates not only the high quality of the faculty's research abilities but also their sense of social responsibility.

"Our university should be a place where humanity can look to find solutions to its problems, and I am proud that our faculty are making great contributions to this crucial field," he says. "What our students are learning is directly tied to addressing society's needs, and they are encouraged to take part in such research to help make the world a better place for everyone."

Charlea Muñoz ('17 M.A.) received her first lessons in helping patients as a linguistics student at UNT. As a graduate research assistant in the audiology and speech language pathology department, she worked with clients who suffered from aphasia, a language disorder caused by stroke or traumatic brain injury.

Now, as a patient resource specialist for the American Cancer Society in Austin, she educates and assists patients with cancer to find the services they need -- from transportation to medical resources and many others. She may set them up with Road to Recovery, in which volunteer drivers transport patients to appointments, or refer them to the Health Insurance Assistance Service program that provides guidance on health insurance options.

"I'm just helping people with long-term illnesses get their voice back," she says.

For example, she recently helped a single mother in her 30s who was diagnosed with breast cancer. The woman was scared and confused.

Muñoz enrolled her in a Look Good Feel Better class, which helps women cope with the side effects of radiation, surgery and chemotherapy by providing wig styling tips as well as makeup and skin care for damaged skin. She also helped her find financial resources by referring her to national foundations that provide assistance for basic needs, such as rent or utilities.

"Just knowing I have your number gives me relief," the woman told Muñoz.

Muñoz says her job can be tough when patients are upset, but she never takes it personally.

"I know their reactions come from a place of stress. They have so much on their plate," she says.

While exciting discoveries are being made in cancer research, she is motivated to focus on different aspects of the patients' needs. She notes the American Cancer Society's motto is "Attacking cancer from every angle."

"I'm attacking it from the social services angle," Muñoz says. "Not only do we need to look at curing the cancer, but also at how we can address the barriers these patients face."

And the rewards of her job?

"That happens every day," Muñoz says, "when I'm able to help patients receive the services they need. That's what I love."

Researcher Evelinn Borrayo ('97 M.A., '99 Ph.D.) works to address cancer health disparities that affect Latinas and other underserved individuals -- populations that are often labeled "hard to reach."

She spearheaded a $1.8 million public health program to encourage Latinas to take the HPV vaccine to prevent cervical cancer. HPV brings stigmas with it, so her team members have to be creative.

"A brochure won't do it," says Borrayo, a professor of psychology at Colorado State University in Fort Collins. "But if you create a video in a soap opera format, and they hear from other Latinas, they're likely to get it."

The program also trains health workers to educate Latinas about the vaccine and the importance of pap smears.

Borrayo began her research as a graduate student at UNT. She was working in the lab of Chuck Guarnaccia, associate professor of psychology, who was studying how health beliefs influence breast cancer screening behaviors of certain populations. Borrayo suggested that Latinas be included in the survey and found that those born in the U.S. had higher incomes and more access, while those born in Mexico had more disparities and were less likely to engage in breast cancer screening behaviors.

In another of Borrayo's research projects, which received $1.9 million from the Patient Center Outcomes Research Institute, she is conducting a clinical trial on an intervention to address the mental challenges that head, neck and lung cancer patients and their caregivers encounter.

"When your face is disfigured or you can't talk or hear, it can be very psychologically traumatic," Borrayo says. "It's important to think about cancer holistically because patients also will often suffer from depression and anxiety."

Similarly, she notes that caregivers suffer but are "the hidden patient" in literature.

"These are people with real needs who are going through a lot, too, while patients are going through treatment," she says.

When Jorge Roman ('13) examined a patient in her 90s with lung cancer who had come to the emergency room for pneumonia, he saw something more. The cancer had advanced to her liver and brain. Because she was too frail to take on more treatment, he helped to transition her to hospice care.

"I got her the right care," he says, "and was able to alleviate the suffering she would have had."

As a physician at the outset of his dermatology career, Roman sees patients with cancer as part of Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas' teaching service. He's committed to helping ease their pain and find the appropriate treatment.

"What makes me happy," he says, "is increasing a person's quality of life. This epitomizes my work, not just in fighting against cancer itself, but in fighting for patients with cancer."

Roman grew up in Fort Worth and received a full scholarship through UNT's Emerald Eagle Scholars program -- becoming the first in his family to graduate from high school and college. At first, he was undecided about his major, but he took to medicine while conducting research on cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in veterans with psychology professor Daniel Taylor and developmental physiology with biology professor Ed Dzialowski.

Roman, who graduated from the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston in 2017, will begin a three-year dermatology residency at New York University in June after completing his internship at Texas Health.

He has published several articles on skin cancer and plans to focus his dermatology practice on its prevention and treatment.

"Taking care of people is humbling," Roman says. "These are very powerful experiences."

Sometimes when Dana Rosencranz ('98 M.S., '02 Ph.D.) works with patients who are undergoing radiation, it can be emotionally challenging for her as well as for them.

"I don't try to hide it," she says. "If I feel like I need to cry, I cry."

As chief medical physicist of Texas Oncology in Paris, a member of the U.S. Oncology Network, Rosencranz creates specialized radiation treatments prescribed by a radiation oncologist for cancer patients and makes sure the equipment meets safety standards. She oversees sites in Greenville and Mount Pleasant in addition to Paris.

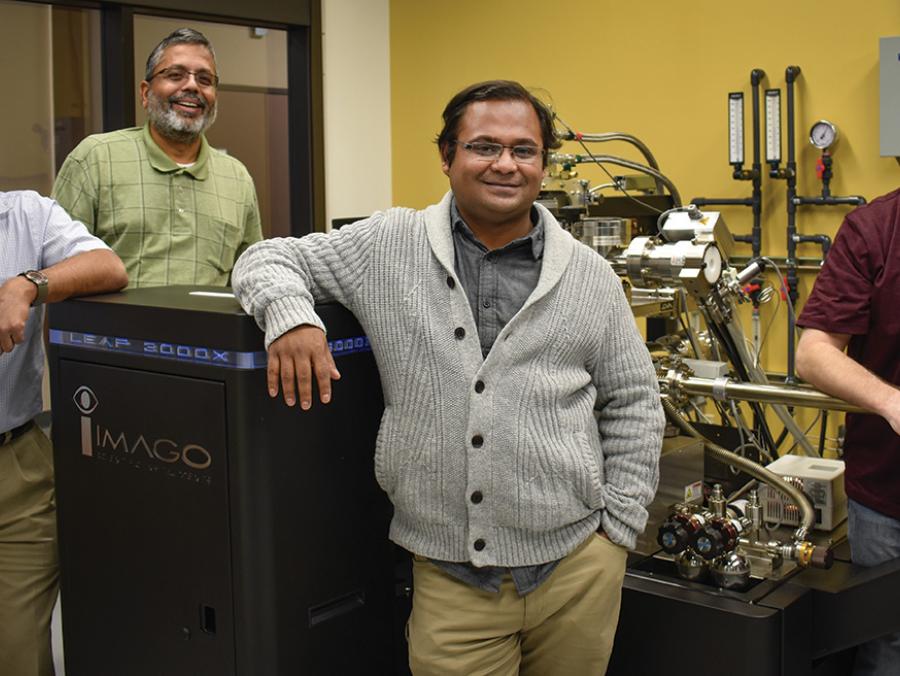

Rosencranz has always been interested in physics thanks to her father, who holds degrees in mathematics and physics. Her career in medical physics took root when Floyd McDaniel, UNT Regents Professor of physics, was visiting a conference in her native Romania and suggested she come to UNT for graduate school. After earning her degrees, she worked for two years establishing and supervising a lab at Advanced Molecular Imaging Systems in Denton, a company that made products for nuclear medicine.

In 2003, Rosencranz started her job with Texas Oncology so she could work with patients directly in a clinical setting. She has always been fascinated with how radiation can be used in treating cancer, but she realizes that patients can be intimidated by radiation therapy.

"I work to make them comfortable by answering their questions," she says.

She also leads a cancer support group, filling a much-needed gap in the rural community of Paris. One patient drove in dark, rainy weather to tell the group his latest scan had shown no presence of cancer.

"When you hear patients talking about their experiences with cancer, it gives you fuel," Rosencranz says. "You're going to work even harder to help them, with all that you have, to fight this horrible disease."