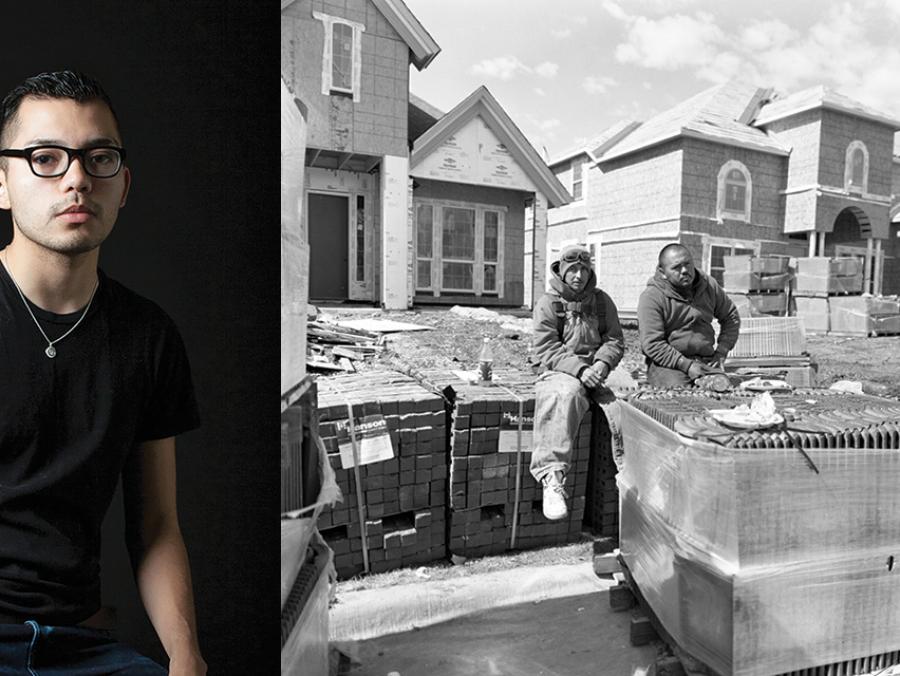

Ryan Crocker ('06) and Christina Treviño ('06) went on a UNT Study Abroad trip to Mexico that changed their lives -- and put them in the midst of one of the leading food movements in the U.S. today.

Ryan Crocker ('06) and Christina Treviño ('06) went on a UNT Study Abroad trip to Mexico that changed their lives -- and put them in the midst of one of the leading food movements in the U.S. today.

Crocker and Treviño, who were students in the College of Public Affairs and Community Service, were assigned to a rural mountain village in the state of Jalisco, where they installed roofs and wired homes with electricity for the impoverished residents. Crocker ate the same food every day -- chicken soup, corn tortillas, cheese, guava and lime. But he noticed something about the meals.

"I never had better corn tortillas in my life," he says. "Everything was produced right there by the family. I just realized there is a lot of richness to that way of life you can't measure by income."

The couple, who met during the program and got married shortly afterward, wanted to bring those fresh ingredients to others. They now farm and run Earthwise Gardens and Produce, a shop in Denton that offers seasonally grown produce and hosts a variety of food events for the community.

More on Farm-to-Table

They're two of many alumni who are leaders in the growing farm-to-table movement, which emphasizes fresh food and sustainable farming. Local and regional foods accounted for $7 billion in sales in 2013, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

These alumni, who come from a wide variety of UNT disciplines, are working to bring locally grown farm products and natural ingredients to restaurants, school cafeterias and grocery stores. And they're creating stronger, healthier communities in doing so.

UNT, which ranks among the world's most sustainable campuses in the GreenMetric Ranking of World Universities and is listed in The Princeton Review's Guide to Green Colleges, is in on the act as well. The Mean Greens dining hall serves 100 percent vegan food. Dining Services uses only organic eggs and works with a local vendor, Ben E. Keith, which provides food deliveries through a state-of-the-art truck with next-generation engines and nitrogen-filled tires that decrease needed deliveries and lower fuel usage.

Classes at UNT, including Philosophy of Food, taught by David Kaplan, associate professor of philosophy, stress the importance of sustainability.

The public now understands better how food is made, often with the use of pesticides and preservatives, and is craving better ingredients, Kaplan says.

"Every time I go to the Mean Greens vegan café, it's always full. The word is out," he says. "I don't think people had this awareness 20 years ago."

Community-supported agriculture

Crocker and Treviño are happy to share this way of life with others.

"It's a completely different way of eating -- instead of eating out of the can, we encourage our customers to eat fresh produce -- vegetables some have never heard of," Crocker says. "Our customers are delighted to discover that they enjoy new vegetables or new ways of preparing food that they weren't accustomed to."

While the trip to Mexico inspired Crocker and Treviño to look into farming, they faced a big challenge. Neither had farmed before.

"The closest experience I had was cutting grass and potting plants," Crocker says.

After they graduated, they lived in England from 2007 to 2009 while Treviño worked as a social worker and Crocker raised their son. They grew strawberries, onions, tomatoes and radishes in their garden, used horse manure from the paddocks for fertilizer and collected rainwater.

Then they lived and worked on a garlic farm in New Mexico, where they learned traditional farming techniques such as plowing with donkeys, rotating crops and watering with flood irrigation -- low-impact, chemical-free farming that taught them the value of healthy soil and ecosystems and community food markets.

They put down roots in Denton in 2011 with a vision to engage the community through nutritious, wholesome food. They began their business by growing vegetables on a quarter-acre vacant lot and selling the produce from their carport and at the weekly Denton Community Market.

Now, after recently merging their farm and community-supported agriculture program with Johnson's Backyard Garden, the leading Texas CSA program, they are helping to expand the urban farm movement in Denton. CSA is a cooperative business model in which farmers sell directly to the consumer. As a CSA provider, they sell weekly shares of fresh produce and other products to subscribing members as well as the general public.

Together with a team of helpers, Crocker and Treviño grow and sell high-quality organic crops such as lettuce, greens, tomatoes, sweet peas, peppers and cantaloupes, and regionally produced items such as honey, pear butter, cheese, pickled beets and free-range meats. They boast a base of loyal customers with the CSA and their storefront business near downtown Denton.

"We just want to focus on the quality of the whole food that we provide," Crocker says. "It's the best way to eat."

Sustainable farming

Denton has another farm, Cardo's Farm Project, established and run by UNT alumni. And Rachel Weaver ('12, '14 M.A.) takes part in every step of the farming process.

Denton has another farm, Cardo's Farm Project, established and run by UNT alumni. And Rachel Weaver ('12, '14 M.A.) takes part in every step of the farming process.

She plants the vegetables and watches them take root -- which can result in an agonizingly long wait when it looks like they're wilting.

"Please make it!" she tells them.

Then she sees the vegetables grown and sold to visitors.

"I feel happy for the people who will eat them," she says.

Cardo's was co-founded in 2011 by Amanda Austin ('10), a drawing and painting major, and Daniel Moon, using some land in Ponder leased to them by Rick "Cardo" Orndoff. They moved their operation to Denton a year later, where their four-acre plot of land is used to grow more than 40 kinds of vegetables -- all without the use of chemicals -- and raise chickens for eggs.

Cardo's also farms and donates the produce from an acre and a half of land at Shiloh Field Community Garden in northeast Denton, the 18 acres that a recent Dallas Morning News article cites as the largest community garden in the U.S. The garden helps feed those living in poverty in Denton County.

Cardo's food is sold at a monthly open house and the Denton Community Market, as well as through CSA boxes. The farm offers school tours and a summer workshop and is open to the public once a month.

Weaver began as a volunteer, helping to harvest vegetables and do other field work when she was studying for her environmental philosophy degree at UNT.

Through her classes in environmental ethics, sustainability, water issues and philosophy of food -- as well as a three-week Study Abroad Sub-Antarctic Biocultural Conservation Program in Chile -- she took part in discussions and was inspired to apply the courses' teachings to her life. She now serves as a paid lead intern at Cardo's, where she supervises the fields and other interns.

"I want to be out there doing something," she says. "UNT helped me connect it all."

Culture of wellness

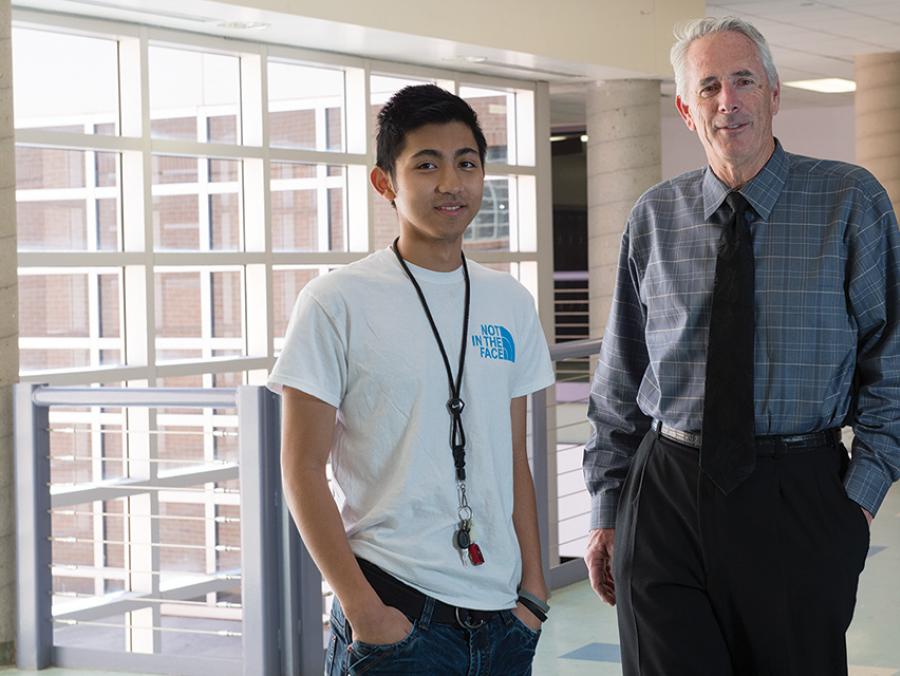

Many kids dream of being a fireman or astronaut. Miguel Villarreal ('82) planned to be a nutritionist.

Many kids dream of being a fireman or astronaut. Miguel Villarreal ('82) planned to be a nutritionist.

"I wanted to teach others about eating well," he says.

Villarreal faithfully watched fitness guru Jack LaLanne on TV, inspiring him to study nutrition at UNT. After graduating, he worked as a food service supervisor and director in the Dallas, Victoria and Plano school districts, at a time when he says schools were more concerned with budgets than nutrition.

In 2002, on the second day of his job for the Novato Unified School District in Marin County, Calif., a dietician told him 35 percent of the students were overweight.

He looked at the menus -- sodas, juice, supersize chips and cookies that were "the size of a platter" -- and thought, "We have got some work to do here." He got rid of the sodas, making up for the $70,000 loss of sales per year by increasing breakfast sales. He bought local, organic produce from the farmers in Marin County. He took out 400 pounds of sugar a day from the menu. He eventually eliminated beef products, which had been recalled eight times during his tenure.

When students enter the cafeteria, they are greeted with a salad bar featuring carrots, jicama, bell peppers and other vegetables. For Meatless Mondays, students can eat veggie burgers, burritos and sunbutter sandwiches, in which sunflower seeds are made into butter -- an alternative for students with peanut allergies. Students also can choose from items such as quesadillas, sandwiches, pasta and rice bowls.

The changes didn't come without resistance. The students weren't easily impressed, so he spoke to them and showed them YouTube videos about eating healthy. Mobile food vendors began selling their products outside the schools, so he helped push a city policy that made it illegal for them to sell within 1,500 feet of schools.

Now he's lauded as a "hero" on Jamie Oliver's Food Revolution website and he's making presentations about his district's success. The district even has a gleaning program in which families can pick unharvested produce at a private farm.

Villarreal tries to connect his efforts to the three C's --the cafeteria, classroom and community.

"This is what it takes," he says. "If we're going to change the culture of wellness, there's got to be education and resources."

Healthy and tasty

Caleb Simpson ('02) became a vegetarian overnight.

Caleb Simpson ('02) became a vegetarian overnight.

A meat-and-potatoes guy, Simpson and his future wife, Kristy ('07), a sociology major, spent a weekend in Austin with her sister, Kaye Herbert, and her husband, Chris Herbert, who ate a raw vegan diet.

"It was an eye-opening experience," says Simpson, a marketing major.

After changing his diet, he lost 10 pounds of excess fat in about two weeks, saw his afternoon crash disappear and found his energy and athletic performance increase. An avid runner and rock climber, he began making his own energy bars since he found similar products didn't use organic ingredients. Three years later, he and Chris Herbert created the Bearded Brothers energy bars that are now sold at Whole Foods, Central Market, Natural Grocers, REI and other locations in the Southwest.

Simpson and Herbert make the bars in their own commercial kitchen. The process is intense. They produce thousands of bars -- mixing all the ingredients during the day, letting them dehydrate overnight in food dehydrators at 115 degrees and then packaging them the next day. Simpson first made the bars in Denton before moving to Austin.

He also creates selling strategies, drawing from the marketing classes -- including one by professor Gopala Ganesh -- that he took at UNT.

Flavors include blueberry vanilla, with almonds, dates, blueberries, vanilla brown rice protein and chia seeds, and maca chocolate, with Mexican cocoa, dates, almonds and maca powder. A label encourages patrons to "congratulate yourself, high five a stranger and keep smiling all day."

"You're getting a cleaner burning fuel," Simpson says. "It's more filling and a better source of energy. We want people to know eating healthy is good for you and it can taste good."

Alchemy of cheese

David Eagle's ('93 M.B.A.) transformation from lawyer to cheese maker began on his overseas travels.

David Eagle's ('93 M.B.A.) transformation from lawyer to cheese maker began on his overseas travels.

"Every time I came back from Europe," he says, "I looked at what we eat here in this country and shook my head in disgust."

Eagle, an amateur chef and foodie, wanted to eat fresh, locally grown food, not processed. And he especially loved the nuances of cheese. So he took a cheese-making workshop in Vermont in 2009 and now runs Eagle Mountain Farmhouse Cheese in Granbury. His products are sold at Central Market and featured on the menus of many Texas restaurants.

"When you make cheese, it's like alchemy," he says. "You're amazed it works every time. You go, 'Wow!'"

He made his first commercial batch in January 2010, and by that spring, he sold his first cheese. It was a mild buttery Gouda-style cheese called Granbury Gold. Scardello, a cheese shop in Dallas, agreed to sell it. He stopped practicing law that year to devote time to cheese making.

Eagle, whose parents, Robert Eagle and Danine Simms, met at North Texas in 1951, says he uses the economics, finance and statistics lessons he learned while in college to run and grow his business.

"Everything you do in your life builds up for what you do later," he says.

He's one of only 25 cheese makers in the state, and he prides himself that his cheese is made and sold locally. And that he's contributing to the local food movement that includes farmers, artisan bakers and chefs.

"The farm-to-table concept is to reconnect, to know where food is coming from so you can make an informed decision about what you're putting in your body," he says. "And to 'connect' to the larger community."

-- Julie West contributed to this story