In the 1880s, Charles Darwin discovered that a blade of grass would no longer grow toward sunlight if the tip was covered with tin foil. This discovery suggested that the tip of the plant was somehow communicating with the rest of the plant to ensure optimal exposure to the sun.

Darwin's discovery created the field of plant signaling, or the study of how plants use chemical signals to control their responses to the environment. More than a century later, Heidi Szemenyei ('97 TAMS, '99, '01), as a graduate student researching plant science at the University of California-San Diego, published a paper in Science magazine about another role of genes responsive to auxin, the same chemical studied by Darwin. She explained how they signal genes to facilitate root initiation in the bottom but not the top of the developing plant.

Szemenyei, who attended UNT's prestigious Texas Academy of Mathematics and Science and later earned bachelor's degrees in biology and anthropology from UNT before her graduate studies, is one of many UNT alumni who are part of a new generation of researchers pushing the boundaries of plant science. In 2008, UNT formed the Signaling Mechanisms in Plants research cluster, a multi-disciplinary team of researchers studying plant signaling to improve energy, agriculture, nutrition and medicine.

"We are trying to help plants do what they do, better, especially in our changing environment. It's getting hotter and dryer, so to produce the same yield in those conditions is challenging," says Kent Chapman, Regents Professor of biology. "What we really need is to get more yield under even worse conditions."

Triple impact

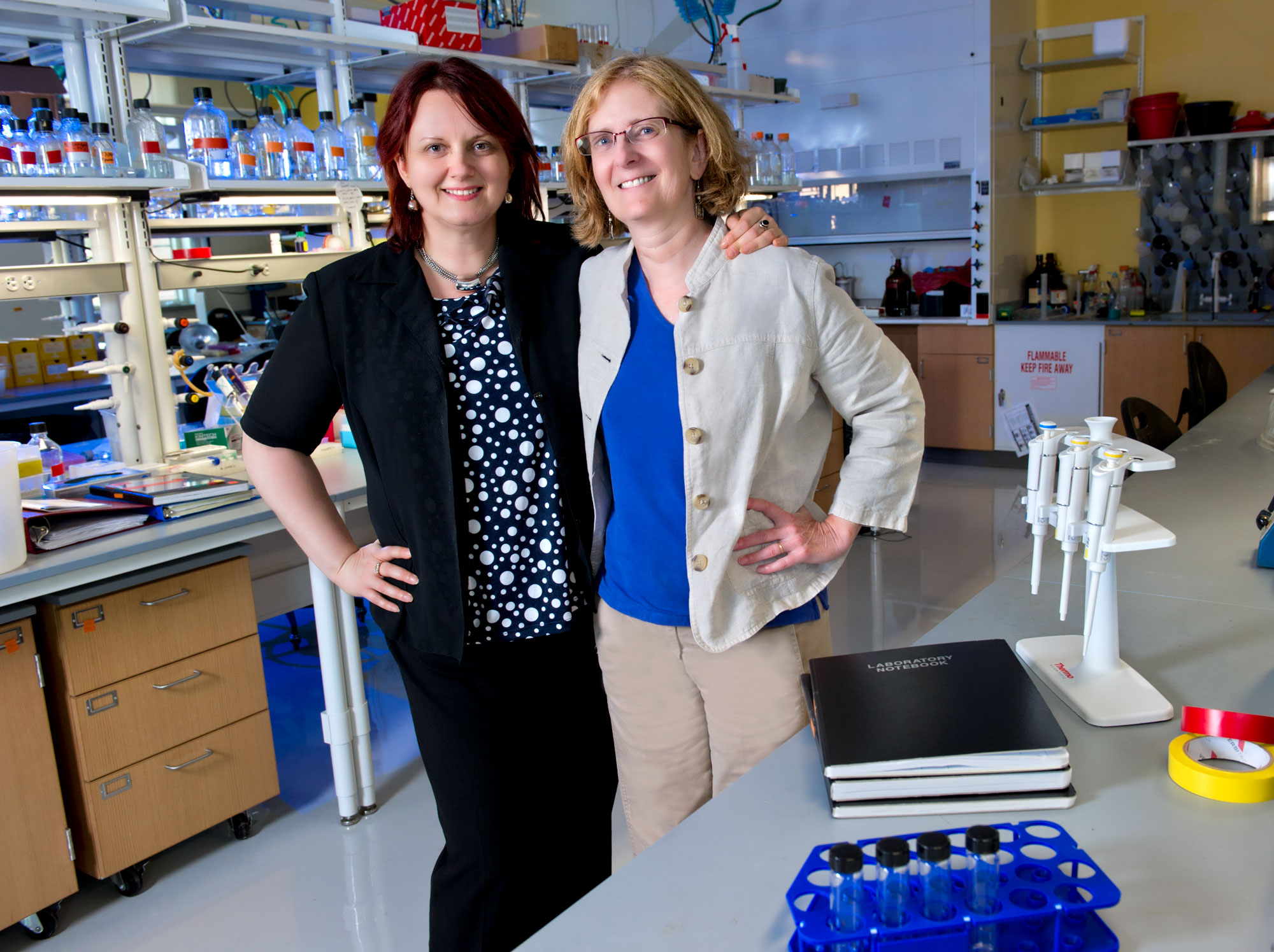

Catalina Pislariu ('06 Ph.D.), a postdoctoral research fellow at the Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation in Ardmore, Okla., is looking for ways to reduce the amount of outside nitrogenous fertilizer that needs to be introduced to crops. Sustainable agriculture is an area she researched while completing her doctorate with Rebecca Dickstein, professor of biology. Pislariu originally came to Texas from Romania to study with Camelia Maier ('92 M.S., '96 Ph.D.), an assistant professor of biology at Texas Woman's University and a fellow Romanian, but she earned her degrees at UNT after becoming interested in Dickstein's work.

Nitrogenous fertilizers supply large amounts of "fixed" nitrogen, reduced forms that plants can use and that are required for productive agriculture, but plants typically absorb only about 30 percent of the fertilizer applied on the soil. The other 70 percent is released into the atmosphere, leaches into the groundwater or runs off into ponds and streams, causing air pollution and water quality issues.

With Dickstein, Pislariu studied the beneficial association between legumes and nitrogen-fixing bacteria in the soil, to better understand how the legumes could obtain fixed nitrogen more efficiently.

"By characterizing legume genes that regulate this environmentally friendly biological process, we might be able to control some of them and make natural nitrogen fixation more efficient," Pislariu says. "This research has a triple impact: on our environment, our food and our health."

Learn more about UNT's research

Pislariu's work on symbiotic mutants was published in Plant Physiology and is expected to be a valuable resource for legume researchers. Pislariu is now focused on characterizing more of the thousands of genes involved in this process at the Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation and continues to collaborate with Dickstein. UNT has a decade-long relationship with the foundation, including joint grant programs, and this fall recruited Richard A. Dixon, who is credited with building the foundation's plant biology program.

A world-renowned specialist in metabolic engineering of plants and a member of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, Dixon will bring new levels of bio-based products expertise to UNT when he begins work in February.

Defense against insects

UNT biology graduate Joe Louis ('11 Ph.D.) is trying to improve the environment through his research on the relationship between plants and insects. Louis earned a master's degree in entomology at Kansas State University and stayed to work on his doctoral degree in molecular biology. When his major professor, Jyoti Shah, came to UNT, so did Louis.

"UNT gave us the opportunity to establish new labs in the new Life Sciences Complex and to collaborate with really great faculty members," Louis says.

Under Shah's direction, Louis studied the mechanisms that allow plants to defend themselves against insect attack. Specifically, Louis used green peach aphids and the Arabidopsis plant as a model system to study what kinds of mechanisms and genes mobilize plant defenses.

"One way to control these infestations is to apply more insecticides. We want to identify the plant's indigenous defenses so we can enhance them, allowing the plants to better resist the insects by themselves," Louis says. "This method would reduce our dependence on costly insecticides, make our environment cleaner and promote better health for humans and animals."

In Shah's lab, Louis was part of a team that identified the role of MPL1, a gene that helps provide defense against aphids. The findings, published in Plant Journal, were significant as they illustrated for the first time how lipids or their products help provide defense against sap-sucking insects.

While at UNT, Louis won many awards, including the International Congress on Insect Neurochemistry and Neurophysiology Student Recognition Award in Insect Physiology, Biochemistry, Toxicology and Molecular Biology from the Entomological Foundation. He also won the John Henry Comstock Graduate Student Award from the Entomological Society of America.

Currently, he works as a postdoctoral fellow at Pennsylvania State University, where he focuses on how insect salivary proteins alter plant defenses.

Bio-based economy

Researchers in UNT's Signaling Mechanisms in Plants cluster have formed strong connections with engineers in UNT's Renewable Bioproducts cluster, which is focused on green solutions for products using plants, bacteria and other bio-agent materials. Researchers from both areas hope to establish a group focused on metabolic engineering to bridge the two clusters.

"There is a whole research area focused on what is called the bio-based economy, a significant field for the future," Chapman says. "We are looking for replacements for all the things that we draw from fossil fuels, including energy and materials. We can significantly lower our carbon footprint by using renewable materials."

Szemenyei, now a project scientist at the Energy Biosciences Institute at the University of California-Berkeley, is working on the cutting edge of the renewable energy movement with projects aimed at converting plants into biofuels more efficiently. She says that although she didn't begin studying plants until later in her graduate career, she developed a passion for research and lab work while attending TAMS. Currently, she is working with tobacco plants to find a way to produce more of the enzymes necessary for creating ethanol naturally.

"One of the most expensive parts of creating cellulosic ethanol is the cost of the enzymes used to break down plant cell walls," Szemenyei says. "We hope to modify the plants to produce those enzymes at very high levels."

Chapman believes the future for plant science is bright at UNT. All of the research cluster members have external funding, including grants from the National Science Foundation, the U.S. Department of Energy, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and Cotton Inc.

Earlier this year, UNT researchers published papers in three consecutive issues of Plant Cell, the journal with the highest impact in the field.

"It really has been the perfect combination. We had the opening of the new Life Sciences Complex, UNT's support and investment in the cluster program and a big recruiting effort for faculty experts, so it all just came together," Chapman says.

"With our growing expertise, we're emerging as one of the leading programs in plant sciences in the country."