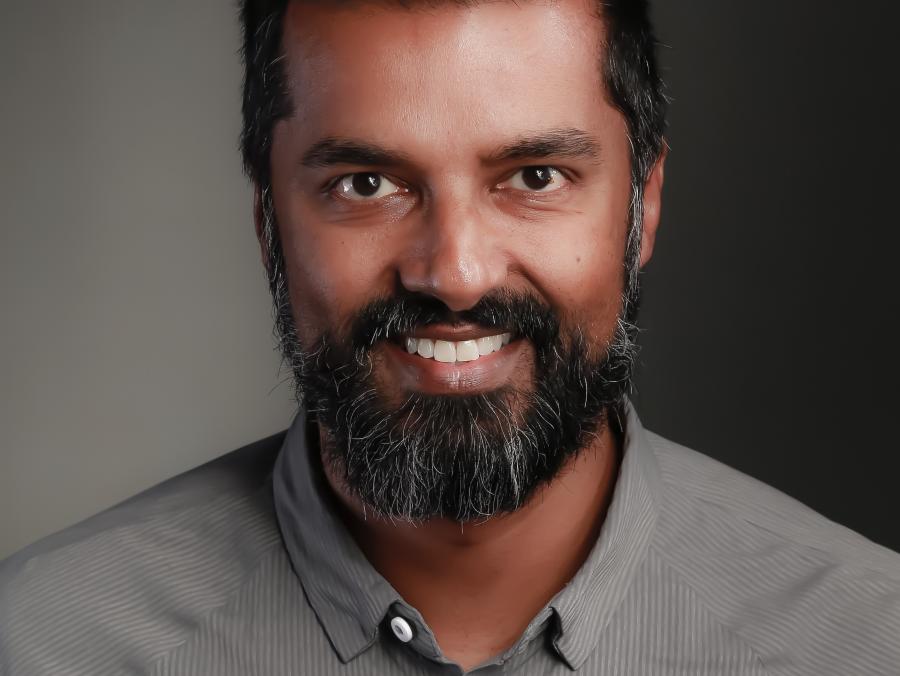

early 25 years after the conclusion of his undergraduate career at Stephen F. Austin, Mike Goddard ('99 M.S., '04 Ed.D.) still looks like a college football player. Tall and broad, he's an imposing figure, the kind of guy you picture bellowing at players from the sidelines or enforcing strict order in the hallways.

But then you see the grin. And the socks. And the lapel pin.

"Every day, there's a theme with the socks and pins," says Goddard, who just last year brought his jovial, outsized presence to the role of Red Oak ISD superintendent. "It's some serious pressure."

At first glance, today's motif isn't obvious -- he's wearing a Kermit the Frog pin and socks emblazoned with a grassy soccer field. But upon closer inspection, the connection is clear: Goddard means green.

He may have played football at SFA, but he says it was at UNT where he tackled his toughest, most rewarding experiences. He first enrolled in the College of Education to pursue a master's degree in counseling before earning a doctorate in educational leadership and administration.

"I never believed I would be able to finish," Goddard says. "But I had professors, like Jack Baier, who believed in me, encouraged me. I had this built-in mentoring all the way through the program."

That's a hallmark of the College of Education: providing the kind of rigorous instruction, real-world experiences and one-on-one support that allow its graduates to seamlessly transition into the classroom -- or out of it. The college's alums achieve not only flexibility but success as they carve their own career paths, moving between roles such as teacher, administrator, department coordinator or policy influencer -- and making measurable differences in students' lives.

It's no surprise when you consider the college is the cornerstone on which UNT was built, tracing its roots to the 1890 founding of the Texas Normal College and Teacher Training Institute. Since then, the College of Education -- whose online graduate education programs are ranked first in Texas and fourth in the nation by U.S. News & World Report -- has firmly established itself as a leader in educating educators.

"Every job I've had in education," Goddard says, "I've used what I learned at UNT."

Goddard's first K-12 position was as a communications applications instructor at McKinney North High School. He signed on as Lovejoy High School's first principal in 2005 and then moved on to Prosper ISD, where he spent seven years as assistant superintendent. Now he is Red Oak's head honcho -- or, as he prefers to view it, a teacher whose classroom includes 900 adults and 6,000 kids.

"I learned a lot about myself at UNT," Goddard says. "I learned to have patience, to stick with the vision I'm trying to instill and to connect with others. It's all about locking arms and walking together."

It's also about lending a helping hand -- and in Goddard's case, that often means oversized Mickey Mouse hands, which he wears to elementary campuses to offer high fives and open car doors in the drop-off lanes. His visits are not only for fun, but also to model his 4 Talons initiative, which helps students realize the importance of life skills like exhibiting academic readiness; staying open to the challenges of learning; being fair, respectful and well rounded; and leaving a legacy through service.

The idea for 4 Talons developed during Goddard's doctoral work, where he created a program evaluation for Champs, which helped UNT student-athletes build life skills beyond athleticism. He identified a problem -- graduation rates were low for college athletes -- and then Baier asked: "What are you going to do about it?"

"He always pushed you in a way that made you feel he had students' best interests at heart," Goddard says. "I've tried to model that. That's what North Texas did for me -- it planted seeds that helped me cultivate these ideas and experiences into tangible things that can help our kids."

After three-and-a-half years at Baylor -- where she cycled through five different majors and a self-described "horrible" GPA -- Patty Donaldson ('87) decided it was time for a break. For a year, she took a breather, re-evaluating her goals and pursuing interests like physical fitness.

During that time, she enrolled in an aerobics class, where she found a great way to stay in shape -- and her true calling.

"Aerobics is very rhythmic, and bless her heart, one of the girls in there had not a rhythmic bone in her body," says Donaldson. "I thought, 'Surely there is something else she can do that is physically active.' And then I knew that's what I wanted to do -- help people find activities that are appropriate for them and encourage them."

Fueled by renewed purpose, she enrolled at UNT where she excelled, earning her B.S. in biology and physical education. Her advisor, Jack Watson, ensured she was placed in classes that helped her achieve her goal of developing students' physical fitness abilities, such as a motor behavior class taught by Peggy Richardson, as well as adapted physical activity for individuals with physical disabilities.

Following graduation, Donaldson taught physics, biology and adapted physical education at Irving High School and then moved on to become an adapted physical education specialist for Katy ISD. In 2007, Donaldson became an instructor and coordinator of Angelina College's health and physical education department in Lufkin, and also now serves as the college's instructor and coordinator of physical, health and safety education.

"I'm teaching future PE teachers and coaches," Donaldson says. "I want my students to get a variety of experiences like I did at UNT so they can be well-rounded educators."

It took Marc Valerin ('11 Ph.D.) the better part of 11 years to earn his doctorate in higher education from UNT. The journey wasn't due to a lack of academic motivation -- the consummate learner counts one bachelor's, three master's, one Ph.D. and three graduate certificates among his educational accomplishments.

Instead, Valerin's momentum was slowed by health issues that included a mini stroke and heart complications, concerns that led him to seek care from doctors at UT Southwestern.

Though he's long since conquered his health problems, Valerin still sees many of those same doctors almost daily. Despite no formal training in health care, he says that his higher education degree -- which he previously used as director of graduate and executive admissions at SMU -- helped him land the role of manager of educational programs at UT Southwestern. He leads the medical education office of the medical school's largest department, internal medicine.

"Health care is completely new to me, but I always look at it in terms of institutions," Valerin says. "I put my knowledge of higher education into the world of an academic medical center. It helps me bridge the gap."

As a student at UNT, Valerin soaked in the knowledge of his professors, including Beverly Bower, Ron Newsom and Barbara Bush. He learned the importance of combining academic scholarship with business acumen from his major professor Baier, a former vice president of student affairs at the University of Alabama Birmingham, and about fundraising and advancement from Pete Lane.

"The leadership piece of being an educator comes from taking business strategies and overlaying them on an education foundation," Valerin says. "You have to understand the operational side of academic institutions and organizations. That's the value I received along the way at UNT."

As a child growing up in Brownsville, Gina Rodriguez ('09 Ph.D.) often visited the elementary school where her mom was principal, making a beeline to the special education classroom.

"I always knew I wanted to work with special kids," says Rodriguez, who as a student struggled with dyslexia and ADHD.

After graduating from what was then the University of Texas at Brownsville, Rodriguez entered the classroom as a special education teacher in her hometown. In 2005, she received her master's in special education and teaching administration from UT- Brownsville, then worked as a behavior resource specialist for Carrollton-Farmers Branch ISD before beginning a Ph.D. in special education at UNT.

She says the journey to a doctorate was tough, but she gained important experiences along the way, such as mentoring from professor Lyndal Bullock and summer internships. Two years after earning her Ph.D., Rodriguez was invited to serve as program manager for the George W. Bush Institute's Middle School Matters initiative.

The former president was looking for someone with a research background and real-life experience to help lead the program, which promotes research-based strategies to drive national policy development that will lead to better academic outcomes for middle school students.

"There were 10 to 15 researchers who focused on different subjects in junior high," she says. "But a seventh-grade English teacher doesn't have time to read a 150-page dissertation about how to write a sentence. So that's where I came in -- I managed the transformation of research to resources more applicable to the classroom."

Being part of Middle School Matters was “one of the coolest things I’ve done so far,” Rodriguez says. But in 2015, she realized she missed working directly in schools. So she transitioned back into a role as behavior and program specialist at Richardson ISD.

“I had some awesome professors who really wanted to help me,” she says. “My whole career has been about giving back.”