English professor Stan Alexander had an idea.

English professor Stan Alexander had an idea.

In 1963, he suggested starting a club at North Texas in which students could play folk songs together. Alexander, who had sung at Austin's popular Threadgill's venue while he earned his Ph.D., asked his young colleague Julian O. Long to help him organize the first meeting.

"All these kids showed up," Long says.

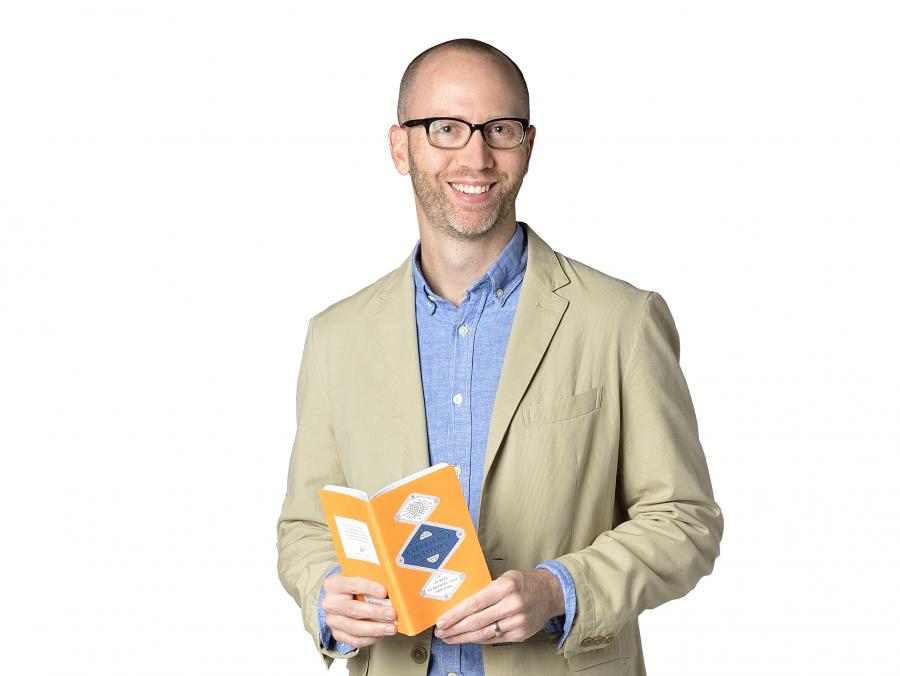

Several of those students -- like generations before and after at UNT -- would become well known in the music world. They went from playing in the Folk Music Club to blazing trails in country and Texas music as songwriters, musicians and entrepreneurs, cementing UNT's reputation as a hub for creativity. The club boasts its own Wikipedia page and a passage in the book The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock by Jan Reid, former senior writer for Texas Monthly.

Its members included the late Steve Fromholz, whose songs have been recorded by Willie Nelson and Lyle Lovett; Michael Martin Murphey, the Grammy-nominated country music star, best known for the hit "Wildfire"; and Eddie Wilson, who founded the Armadillo World Headquarters in Austin, which hosted the biggest names in rock and country music in the 1970s. Others such as Donnie F. Brooks and Travis Holland also had successful careers.

Even after the club disbanded in the mid-1960s, the folk music scene on campus influenced students Ray Wylie Hubbard, who became part of country music's outlaw movement in the 1970s, and B.W. Stevenson, who wrote and recorded the hit song "My Maria."

And it all began in the faculty lounge of UNT's Auditorium Building.

Creating music

The club's meeting format was simple. Its members, from a variety of majors, met every week and sang to each other.

"It was just a crowded room full of music," says Wilson, who majored in English and philosophy. "A number of them had guitars, half of them wanting to play and half not wanting to hear what the others wanted to play. Whoever spoke up first with authority carried the day."

"We never had any dead time," says Long, who left North Texas in 1965 and then returned to work for 25 years in the English department and graduate dean's office. "There was music the whole meeting."

The songs ranged from bluegrass classics to current hits. Students also sang from the popular album of 1964 -- Bob Dylan's The Times They Are A-Changin'. Some members stood out -- the sponsor, Alexander, being one of them. A classmate told Wilson about the club that was run by the teacher with a rich baritone voice.

"And I knew it had to be Stan Alexander," Wilson says, adding that he had heard Alexander perform at Threadgill's when he was growing up in Austin. "All I remember is the reason to go was to hear Stan sing."

Fromholz, who served as president of the club, was also noted for his singing.

"Steve always had a magnificent, big voice," Wilson says.

That voice blended well with the voices of two other students -- Murphey, who went by the name Mike, and his high school friend Patti Lohman Brooks ('67). Called the Mike Murphey Trio, they modeled themselves after Peter, Paul and Mary, the popular folk group. They first performed at a 1963 Homecoming talent show, singing "Man of Constant Sorrow." They also played at campus events and the Denton country club.

That voice blended well with the voices of two other students -- Murphey, who went by the name Mike, and his high school friend Patti Lohman Brooks ('67). Called the Mike Murphey Trio, they modeled themselves after Peter, Paul and Mary, the popular folk group. They first performed at a 1963 Homecoming talent show, singing "Man of Constant Sorrow." They also played at campus events and the Denton country club.

"We walked around like troubadours," says Lohman Brooks, who majored in elementary education. "We never pretended we were anything special."

Murphey, who also played with The Dallas County Jug Band, served as freshman class president and was active in student groups, such as the Independent Students' Organization and Debate Club.

"People like Mike Murphey were stars," Long says. "Playing better than any of us."

The club disbanded after Alexander left to teach at Stephen F. Austin University in 1965. But its influence remained. When Hubbard attended from 1967 to 1968, he saw students, dressed in corduroy jackets and pants, playing the guitar on campus.

"Denton had a very cool folk music scene," says Hubbard, who majored in English and wrote for The Campus Chat while at North Texas. "The town was very small, but it was a very knowledgeable music community."

"Denton had a very cool folk music scene," says Hubbard, who majored in English and wrote for The Campus Chat while at North Texas. "The town was very small, but it was a very knowledgeable music community."

The local Presbyterian church hosted hootenannies, and Hubbard played with Stevenson, who attended North Texas as an opera student from 1967 to 1968 before joining the U.S. Air Force.

Students protested against the Vietnam War and for the civil and women's rights movements, while listening to new music from the Beatles and the Rolling Stones.

"It was a very exciting, vibrant, turbulent time," Hubbard says, adding that since the Internet didn't exist, "you heard about culture and politics through albums."

Making legends

After they left North Texas, the club members ventured out into the world, playing in coffeehouses and clubs in Texas and New York City. Murphey, Fromholz and Stevenson often played at a Dallas club, the Rubaiyat. Wilson held several jobs, including managing the band Shiva's Headband, headed by Folk Music Club member Spencer Perskin, after settling in Austin.

"Well, you got to do something," Wilson says. "I found this gigantic empty building and became an entrepreneur."

He turned that building into the Armadillo World Headquarters, which hosted such acts as Nelson, Bruce Springsteen, The Clash, the Grateful Dead and AC/DC during its tenure from 1970 to 1980 -- becoming one of the most legendary venues in music history. Arts and Labor Magazine recently put out a list of the "Twenty-Five Most Significant and/or Notorious Nights in Austin Music History" -- and five took place at the Armadillo.

He turned that building into the Armadillo World Headquarters, which hosted such acts as Nelson, Bruce Springsteen, The Clash, the Grateful Dead and AC/DC during its tenure from 1970 to 1980 -- becoming one of the most legendary venues in music history. Arts and Labor Magazine recently put out a list of the "Twenty-Five Most Significant and/or Notorious Nights in Austin Music History" -- and five took place at the Armadillo.

"It was quite humbling," Wilson says.

He now runs another legendary Austin landmark -- Threadgill's. One of its two locations features memorabilia from the Armadillo. Wilson's former classmate Murphey also played at the Armadillo, one of many stops in his storied career. In the 1970s, Murphey produced such songs as "Geronimo's Cadillac" as part of the "Cosmic Cowboy" movement -- progressive country and outlaw country music that distinguished the Austin music scene. His biggest hit came in 1975 with "Wildfire," which peaked at No. 3 on the Billboard Top 100 chart.

Long remembers waking up one morning and hearing the song on the radio.

"My," he thought, "I knew that kid at North Texas."

Murphey later scored other country hits on the charts, including "What's Forever For," and he's best known for his cowboy songs.

Murphey later scored other country hits on the charts, including "What's Forever For," and he's best known for his cowboy songs.

Fromholz, who died in 2014, also saw great success on the radio as a songwriter. He penned "I'd Have to be Crazy," which became a hit for Nelson, and Lovett and other artists have recorded a set of his songs dubbed "Texas Trilogy." Fromholz, an English major at North Texas, served as the Texas Poet Laureate in 2007.

"He was just this fabulous character," says Lohman Brooks, a longtime teacher who is now head of the lower school at Lakehill Preparatory School in Dallas. "He was a normal guy who loved music and was grateful that others enjoyed his music."

Brooks and Holland had careers as back-up musicians. Holland played guitar for Fromholz, Murphey and other acts. Brooks, a harmonica player, joined the folk music scene in New York City. He played as part of Waylon Jennings' band and in sessions for Jerry Jeff Walker, Billy Joel, Murphey and others. His work can be heard in the Ken Burns documentary The Civil War and the movie Fame. Brooks died in 2000.

"You need a harmonica player?" Hubbard says. "Don was just phenomenal."

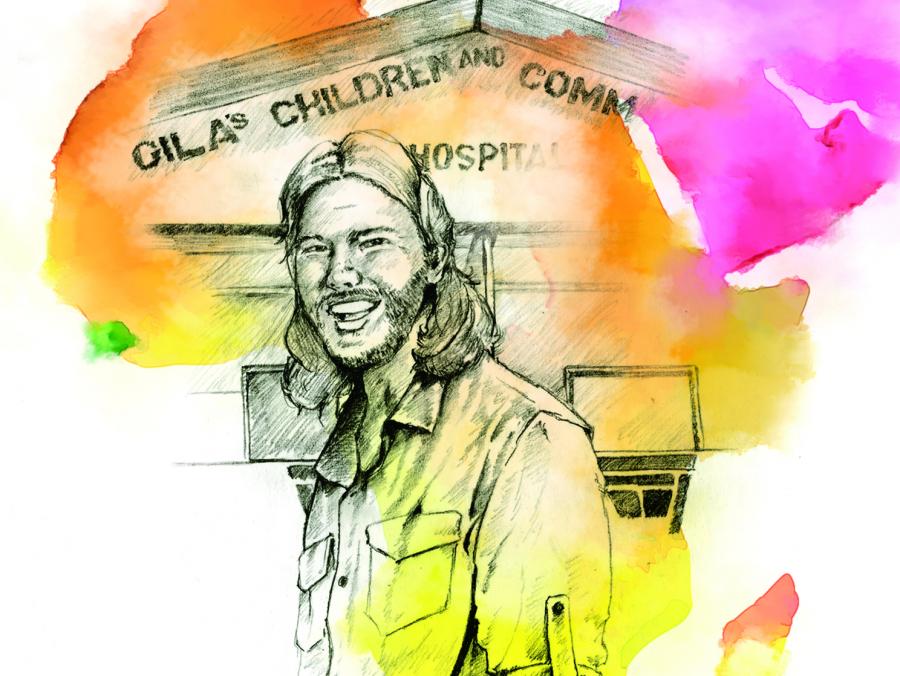

Hubbard became well known in the 1970s with songs such as "Up Against the Wall Redneck Mother" recorded by Walker. A frequent presence on the tour circuit, he continues writing and performing, with hits like "Snake Farm" and "Wanna Rock and Roll."

Stevenson scored with the single "My Maria" in 1973. He died in 1988, but the song became a hit again when Brooks & Dunn took it to the top of the country charts in 1996.

The success of the Folk Music Club's members makes sense to Hubbard.

"It left its mark on people because they were drawn to each other. It was folks hanging together, coming together because of folk music," Hubbard says.

The club's atmosphere and camaraderie inspired others to unleash their creativity.

Alexander, the group's founder, says the collaborative experience of the club encouraged members to perform well.

"Folk music is very engaging," he says. "The best sort of club is when everybody wants to participate."

But he says its purpose was simple.

"Mostly it was just fun."