|

|||||||||||||||||

|

From Rags to Riches

|

When Ronald Waranch ('54) decided to major in accounting at North Texas, he was nervous about fitting in with prosperous people in the business world. While growing up in an impoverished family, he had little opportunity to learn social graces.

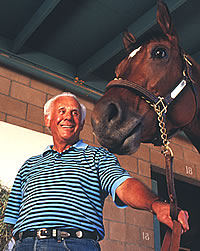

"I didn't know what fork to use during a dinner party or how to greet people," he says. Waranch enrolled in a "Social Fundamentals" course taught by Editha Luecke in the School of Home Economics. He never forgot what Luecke taught him. More than 20 years later, Waranch, the owner of Villa Pacific Building Co. in Los Angeles and a member of the Horatio Alger Association of Distinguished Americans, named one of his racehorses "Dr. Luecke." "After taking Dr. Luecke's course, I was prepared to make a favorable appearance. It helped me as much as my accounting courses," he says.

The Horatio Alger Association selects 10 Americans as lifetime members each year for overcoming humble beginnings and adversity to achieve personal and professional success. Association members — community leaders who have a strong commitment to assisting those less fortunate than themselves — sponsor more than $4 million in scholarships for high school seniors. The students have proven that they can overcome poverty and other barriers to pursue college degrees — just as Waranch did. Born in Gettysburg, Pa., during the Depression, Waranch grew up in Corpus Christi. His father, who lost most of his money in the 1929 stock market crash, bought a warehouse and supply yard for oil drillers. But he earned little money at first. For four years, the Waranch family lived in a motel room, sharing the motel's outhouse with other renters.

When World War II began and oil drilling supplies were no longer in demand, Waranch's father decided to try his own luck at drilling for oil — only to go broke. Waranch, then 10 years old, helped his family financially by making deliveries for a pharmacy. He also had morning and evening paper routes. He worked part time during the school year and full time each summer until he graduated from high school. "My only regret now about working is that I couldn't participate in high school athletics. I've always been a big sports fan, and I think I would have liked doing that," Waranch says. "But I honestly didn't know to miss anything. Work was a part of my life, and I was determined to be the best at whatever job I had at the time. I rode my bicycle as fast as I could when I made deliveries, and I tried to be the best paper boy."

Waranch says his parents never suggested college as an option for him after high school, but he considered it anyway. "I just felt that advanced education was important," he says. "I had no direction or goals. I just wanted to do something that was dignified." He attended Del Mar College, a community college in Corpus Christi, before transferring to North Texas the second semester of his sophomore year. "I had never heard of it before someone mentioned it to me, but it sounded like a place where I could fit in," he says. Waranch arrived at North Texas in January 1950 and joined a Marine program called Platoon Leaders Class. The program provided him with income and a trip to Quantico, Va., in the summer for two weeks of training. "I had never had a vacation, so I thought joining PLC was a good way to get one. I thought it would be fun to go to Virginia," he says. While Waranch was in Quantico in June 1950, North Korea invaded the Republic of South Korea, and President Harry S. Truman committed U.S. troops to the conflict. "The word was that the war was going to last only six months, so I resigned from PLC and enlisted in the Marines. I wanted to take advantage of the G.I. Bill," Waranch says. He served with a military police unit in Korea and Japan for the next 16 months and realized that he needed to go back to college and be a better student when he returned. "Most of the enlisted Marines were high school dropouts — kids who had no goals in life. They would end up working in menial jobs. I realized that if I didn't have an education, I would end up like them," he says. Waranch returned to North Texas in the spring of 1952, where he made time to join the Trojans fraternity (now the UNT chapter of Phi Kappa Sigma) and serve on the InterFraternity Council.

Working for several companies before and after graduation, Waranch eventually moved to Los Angeles to join Trousdale Construction. He had never worked for a building company before, but he learned quickly by observing others at their jobs and became the company's president in 1967. After merging Trousdale with Lear Siegler, Waranch spent three years in Hawaii with the new Trousdale Division before resigning in 1972 and returning to Los Angeles to start Villa Pacific Building Co. He spent a year searching for his first project and says he would not have located his first property if he didn't follow one of his rules: Always return telephone calls. Waranch recalls receiving a phone message from an acquaintance. He didn't want to return the call but did anyway, and he learned that a major builder had dropped out of purchasing property behind a Catholic school in Los Angeles County. Within three weeks, Waranch had plans to build Cabrini Villas — 863 condominiums and the largest project of its type in the county. Success didn't come right away, however. The area's economy slumped, and the condominiums weren't selling. "I spoke with a bankruptcy attorney just in case I had to file," Waranch says. "Then, suddenly, the market changed and the economy improved. I was lucky. My brush with disaster was the first time I thought about what my father had gone through." Since that first project, Waranch has become financially successful as a dominant homebuilder in Southern California, with his company constructing more than 15,000 residential units. The first phase of his latest project, Rancho Vista in Palmdale, was completed this year. The project includes 4,000 homes, a shopping center, a golf course and schools.

The boy from Corpus Christi who didn't live in a house with indoor plumbing until age 6 now resides in an affluent golf course community north of San Diego and actively breeds and races thoroughbreds. One horse, Ronton, ran in the 2000 Kentucky Derby. Waranch, however, hasn't kept all of his wealth to himself. A strong supporter of education, he's funded special teachers for memory development, speed reading and speed math at the Rancho Vista elementary school. His company has sponsored several youth sports teams, presented basketball clinics and helped to fund a children's wing at a Los Angeles hospital. Waranch also currently serves on the board of the Horatio Alger Association, and he's contributed financially to Fresh Start Surgical Gifts, an organization in San Diego that provides free reconstructive plastic surgery and medical services to children and young adults with physical deformities from financially disadvantaged families. The surgeries are performed seven times a year in San Diego County. At North Texas, Waranch established a scholarship fund in his name and recently gave more than $1 million for the Ronald C. Waranch Tennis Pavilion, which will be built on the Eagle Point Campus. He also made $1 million bequests to the Horatio Alger Foundation and to Savannah College of Art and Design. "My mother was very generous with her time in trying to help others with their problems," he says. "I think I inherited that from her. I've tried to share what funds I've had — modestly at first. Now, if I see a need, I have the opportunity to provide for that need." He's looking forward to interacting with the students who are named Horatio Alger Scholars. "I want my life story to serve as a role model for them," he says. "I took advantage of opportunities that came my way, and I hope they will too. "I feel I'm a very fortunate person. There have been some downs in my life, but the ups have far outweighed the downs."

|

||||||||||||||||||||||